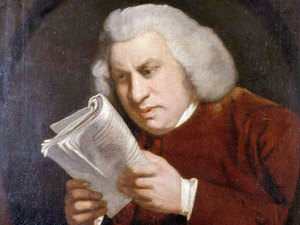

JOHNSON, SAMUEL

1709 - 1784 from England

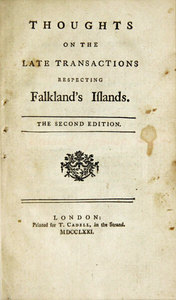

author and lexicographer, was born in Lichfield, Staffs on 7 September 1709, the elder son of Michael Johnson, bookseller, and Sarah Johnson, née Ford. He was educated at Lichfield Grammar School, the King Edward VI School, Stourbridge, and in 1728 he went to Pembroke College, Oxford, leaving in 1729 without a degree. Unable to earn a living as a teacher in the provinces, he moved to London in 1737 and embarked on a writing career. Beginning with a series of political pamphlets and parliamentary reports for the Gentleman's Magazine, his work over the next three decades was prolific and varied. In his sixties, encouraged by Henry Thrale, MP for Southwark, Johnson returned to political pamphleteering in support of the government of Lord North. Newly appointed Prime Minister by George III, North consolidated his hold on government as a result of the Falkland Islands crisis of 1770. In June of that year the Spanish seized the settlement at Port Egmont (West Falkland) ousting the British military garrison based there. In February 1771 North easily won a vote in Parliament for a diplomatic agreement which had been negotiated with Spain. Johnson's pamphlet Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Islands, was written in 1771. It was directly provoked by a letter written by 'Junius' (the anonymous pamphleteer and master of political polemic whose identity remains a matter of speculation).

Between 1769 and 1772 a series of letters from Junius appeared in the Public Advertiser voicing the opposition's dislike of the settlement. In support of North, Johnson described the Islands as 'a few spots of earth... in the deserts of the ocean,' and gave a lucid résumé of their history up to the Spanish seizure of Port Egmont. The 1771 settlement allowed the British garrison to return to Port Egmont: 'an island' Johnson wrote 'thrown aside from human use, stormy in winter, and barren in summer; an island, which not the southern savages have dignified with habitation; where a garrison must be kept in a state that contemplates with envy the exiles of Siberia; of which the expense will be perpetual, and the use only occasional'. Johnson played down the British failure to settle the question of sovereignty, arguing that Britain's honour had been satisfied with the restitution of Port Egmont. 'A war declared for the empty sound of an ancient title to a Magellanick rock' could not have been justified. Johnson's language increased in hyperbole as he put the case for peace, answering and equalling Junius with his polemic. The diplomatic settlement of the Falklands crisis, Johnson concluded, had left the warmongering Junius toothless and he could now be tolerated since 'no man hates a worm as he hates a viper'.

In 1775 Oxford awarded Johnson an MA for services to literature, in particular for his best known work, A Dictionary of the English Language. He died in London in 1784. He married Elizabeth Porter, widow, in 1735; he had no children. Johnson's observations have been frequently quoted, usually by those who wish to denigrate the Islands. Johnson was unfair, but his rhetoric sprang from political passions in London rather than any close knowledge or experience.

External links

See: [BBC 4] Samuel Johnson: The Dictionary Man (YouTube video 2012)

Comments

Revisions

August 2019 External link added

December 2019 One additional illustration added