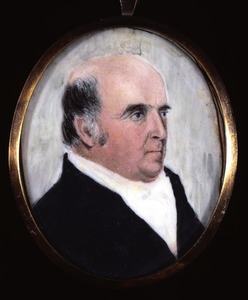

ROTCH, FRANCIS

1750 - 1822 from United States

American whaler, was born in Nantucket, Mass on 30 September 1750, son of Joseph Rotch, the foremost whaling merchant in the American colonies and Love Coffin, née Macy, daughter of two of Nantucket Island's oldest whaling families. An older brother, William, achieved international prominence as a whaling merchant in England, France and America. Francis Rotch, on the other hand, came of age with an inventive cast of mind, which led him to focus on improving the methods and implements used to catch whales and process whale oil. In 1765, the family moved to a harbourside village on the mainland which would grow to become New Bedford, home of America's largest whaling fleet. But before that could happen, the deteriorating relationship between Great Britain and its American colonies profoundly affected the established procedures of the whaling trade, as well as the lives of the Rotches. Under the established mercantile pattern of the time, Rotch vessels regularly carried sperm whale oil and spermaceti candles to London, their largest market. In the fall of 1773, two of these ships took on return cargoes of East India Company tea. Francis Rotch went to Boston to receive them, but Britain's newly imposed tax on tea aroused an assembly of patriots who in the guise of Mohawk Indians dumped the tea into the harbour. Responding to this 'Boston Tea Party', the royal governor of Massachusetts closed the port of Boston and set the stage for America's war for independence from British rule.

At this juncture, Rotch entered into partnership with Aaron Lopez, a highly successful merchant of Newport, Rhode Island, to explore ways to continue whaling at a time when Britain's navy ruled the seas. Their plan was bold, entailing the establishment of a base in the Falkland Islands from which to exploit recently discovered sperm whale grounds off the south-east coast of South America. It also assumed that arrangements could be made to send the oil directly to London for marketing by their agents. In the fall of 1775, six months after the War of Independence began, Rotch and Lopez assembled 16 whaling ships at Martha's Vineyard and sent them off to the Falklands. Rotch himself sailed for London to convince the British government of the benefits that would accrue from the venture and to obtain assurances of protection for the vessels from seizure and their crews from impressment. The London firm of Haley and Hopkins agreed to receive and market whatever oil might be taken. Writing to Lopez, Rotch later admitted that not everything had gone smoothly. In fact 'various unfortunate occurrences nearly defeated all of our purposes, the most material of which was the seizure of five of our vessels'. Taken off the Azores by the British Navy, the ships were sent to London, where 'by tedious application', Rotch managed to get them released. The Minerva, however, was unfit to go to sea and had to be sold, and the Diana too was found unfit.

Early in 1776, Rotch left for the Falklands in the Nancy, one of his two store ships. He took with him three whaling captains to fill vacancies which might have occurred in the fleet and remained in the Islands for 'many months,' later describing them as the 'happiest period of my life'. Returning to London in 1777, he left no records or accounts from which to judge the success or failure of his venture. The fact that he and Lopez sought protection agreements for 14 additional whaling ships suggests that whaling from the Falklands not only continued but may even have increased. On the other hand, a brief summary of the expedition written in 1826 by Francis's nephew, Thomas Rotch, concludes with the statement which reflects the family's view that 'after spending many months in the Islands without the least prospect of succeeding in the enterprise, Francis abandoned it, returned to England and wound up the concern with a total loss of the capital invested in it'.

Rotch spent much of his remaining life abroad, first in the London home of Mary Haley, now owner and manager of her late husband's firm, then in the French ports of Dunkirk, Lorient and Le Havre, where in return for French bounties, he and his brother William Rotch based their whaling ships, rather than subject their oil to the prohibitive tariff on foreign whale oil now in effect in Britain. When revolution came to France, Francis Rotch returned to New Bedford to spend the remaining years of an eventful life designing and patenting various devices to transform whaling - inventions which alas went unheeded. He married twice, to Deborah Fleeming and to Nancy Rotch, (a cousin aged 91 - surely a marriage of convenience to allow them to share a house) but had no children. He died on 20 May 1820 in New Bedford.