SHEPPARD, ROBERT CARL

1897 - 1954 from Canada

master mariner, born in St John’s Newfoundland on 31 January 1897 to Anna Laura Sheppard (née Davis) of Harbour Grace and Robert Sheppard of St John’s, also a master mariner.

After schooling at Bishop Feild College, St John’s, he enlisted on 8 September 1914 in the Newfoundland Regiment as one of the first five hundred dispatched to Europe that October to become a British Army unit. After seeing action at Gallipoli and Suvla, he was wounded at Beaumont Hamel and invalided home to be honourably discharged on 28 March 1917.

Recommended by the military for formal seamanship training, Sheppard obtained a master’s certificate and voyaged to the Caribbean, Spain, Greece and Portugal, routes familiar to generations of Newfoundlanders whose schooners carried salt fish in one direction and returned with rum, molasses, and other locally unavailable products.

On 1 March 1920 he married Sadie Addison Kean, granddaughter of the famed Newfoundland sealing skipper Captain Abram Kean, then came ashore after the birth of his son to succeed his grandfather as keeper from 1924-38 of the Fort Amherst light at the entrance to St John’s harbour.

Sheppard saw convoy service with the British merchant navy during World War II and ferried captured vessels to England and the Caribbean.

After becoming the St John’s harbour master, he accepted a request from local merchants Bowring Brothers to command the Antarctic voyage of their venerable sealer Eagle, requisitioned in September 1944 by the Admiralty to support Operation Tabarin, a secret expedition to reinforce British sovereignty claims to the Falkland Islands Dependencies by establishing permanent scientific and meteorological bases. After the meteorological and logistics Base B on Deception Island, South Shetland Islands, was set up, an attempt was made in February 1944 by HMS William Scoresby and the Falkland Islands Company ship Fitzroy to establish the main sledging facility, Base A, at Hope Bay, Graham Land. This was prevented by severe ice, and the base was instead established at Port Lockroy, Wienke Island, off the Danco Coast of Graham Land. Newfoundland’s sealing fleet was called upon to supply the ice-strengthened capability needed to establish a presence on mainland Antarctica by providing logistic support for the construction of what became Base D.

Sheppard and his crew of twenty-seven Newfoundlanders, including an eighty-year-old bosun, a seventy-seven year old chief engineer and a sixty-eight year old chief officer, took Eagle out of St John’s on 24 October 1944 in convoy WB 133 to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to load specialist stores before arriving at Stanley on 17 January 1945 after making seven coaling stops at ports in the Caribbean and South America. Loaded with new expedition personnel, construction materials, and huskies shipped south from Labrador via the United Kingdom,

Eagle entered Port Foster, Deception Island (Base B), on 29 January. During this leg of the voyage, Sheppard sustained broken ribs and internal damage after he was washed off the bridge onto the deck, an event which contributed to later medical difficulties. Although the expedition’s doctor, Surgeon Lieutenant Eric Back, recommended that he return to Stanley for treatment, Sheppard refused on the grounds that this would mean the loss of Eagle and significantly reduce the chances of Base D being established.

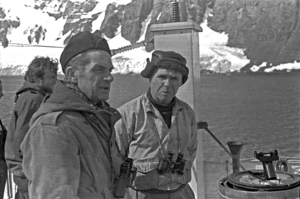

To give him some recovery time, the Operation Tabarin leader, Lieutenant Commander James Marr, delayed Eagle’s sailing for the bases by ten days. Thus, began a mutual relationship of respect and friendship between the crew and future Hope Bay shore personnel, leading the newly arrived surveyor, Lieutenant David James to record that the ship was a ‘villainously dirty wooden steamer…[whose] skipper being 50 but looking 35 [had] a soft voice and beautiful manners which clearly cloaked a character of considerable determination’.

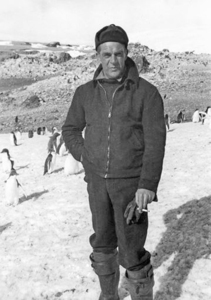

Sheppard at the ruined NORDENSKJOLD...

Similarly, Captain Andrew Taylor, Royal Canadian Engineers, who took over as expedition commander and Base D leader after Marr was repatriated to England on medical grounds, found Sheppard ‘a fine looking silvery haired man approaching fifty, [when joining him] in an enjoyable cup of good coffee and some lobster, about the last thing one expects to find on an Antarctic table’. Perhaps due to their Canada/Newfoundland backgrounds, Taylor and Sheppard became firm friends, corresponding with each other for many years afterwards.

Following the loading of further supplies and construction materials for what became Eagle House, the rejuvenated Sheppard took Eagle out of Deception Island on 11 February and arrived at Hope Bay the following day. As he eloquently stated in his private journal, during the voyage ‘even I, who cannot see much to get excited about by masses of desolate ice-covered rock, was, for the time being at any rate, captivated by the terrible lonely and majestic beauty of it all.’ But later, ‘to me, the handicraft of man in his creation of a beautiful piece of architecture or a fine-lined ship is much more to be admired and pleasing to the eye’. His upbringing among the rugged and often inhospitable coastal scenery of Newfoundland had made him hard to impress!

Shortly thereafter, with the expedition’s carpenter Lewis ‘Chippy’ Ashton, he followed botanist Mackenzie Lamb (from 1971 Elke Mackenzie), ‘the best scientific mind amongst us, and a diligent worker and courteous gentleman’, to an abandoned stone refuge built by three members of Otto NORDENSKJOLD’s Swedish South Polar Expedition (1901-04) when forced to overwinter in 1902-03.

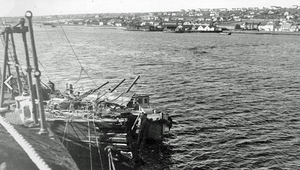

As construction proceeded, Sheppard took Eagle back to Deception Island on 2 March to collect further materials. However, much to his concern about the encroaching winter and the possibility of being trapped in Hope Bay, bad weather prevented him from returning until 12 March. His concerns were realized on 17 March when ice calving from the nearby Depot Glacier during a storm severely damaged his ship’s bow. Faced with flooding and the potential abandonment of Eagle with possible loss of life, Sheppard made the decision during a lull in the storm to run for Stanley where he arrived on 24 March albeit with some of the base cargo still on board.

As Back recorded as she limped out of Hope Bay, ‘May God preserve the Eagle and her brave crew.’ Following temporary repairs and dry-docking in Montevideo, he returned Eagle to St John’s on 2 October after a round trip of 18,571 nautical miles in almost twelve months. Of his original crew, three were repatriated for medical reasons during the voyage south, and one was buried in Recife on the return voyage after sustaining head injuries when coaling at Rio de Janeiro.

At Sheppard’s suggestion, Taylor proposed that the Colonial Office charter one of the Newfoundland government’s ‘Splinter Fleet’, ten diesel powered wooden vessels built locally in the 1940s for coastal work, to replace the damaged, slow, and unsuitable Eagle. This done, Sheppard was asked to command the MV Trepassey, a mission which he readily accepted being anxious to see the Operation Tabarin members Hope Bay party again and expand the bases for the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS), the 1945 successor to Operation Tabarin.

Trepassey left St John’s on 20 November 1945 carrying three of the Eagle’s crew, a second load of fifty-five huskies from Labrador under the supervision of FIDS members Surgeon Lieutenant R C SLESSOR, and sub Lieutenant T P O’Sullivan, Sheppard’s son Robert Austin in the crew, and wife Sadie who accompanied them as far as Montevideo. Stopping only at Recife and Montevideo, Sheppard brought Trepassey into Stanley on 31 December 1945 after a voyage made eventful by the decomposition of whale meat carried as food for the huskies!

From January to March 1946 Sheppard and the Trepassey resupplied Bases A, B, and D, and established C (Sandejord Bay/Cape Geddes), E (Trepassey House, Stonington, Marguerite Bay) and F (Winter Island, Argentine Islands), all now operating under the aegis of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS), the 1945 successor to Operation Tabarin. A visit to the Argentine Base Orcadas on Laurie Island, South Orkney Islands, led Sheppard to conclude that ‘there was no doubt about the fact that the Argentine government intended a lengthy occupation of the place.’

However, the relationships between Sheppard and his crew and the FIDS personnel did not reach the level of mutual respect developed during the Eagle voyage, in large measure due to what some considered the wish of the FIDS first field leader Surgeon Commander Edward W Bingham, the replacement for Captain Andrew Taylor, to separate personnel from the two expeditions. Those at Hope Bay had become disenchanted by what they considered to an apparent lack of interest from the Colonial Office and the FIDS in London on their work. Bingham did not want the malaise to spread to his new party. This particularly disappointed those about to leave Hope Bay, and the departing Taylor later wrote to Sheppard ‘as you well know, I’m sure, we all felt much more closely attached to you and your men and the old Eagle than we did to any of the others we had contact with, and it was with a disappointment almost amounting to shame that we found ourselves taking passage on the Scorseby rather than with you on the Eagle’.

Perhaps unable to accept that the Trepassey’s crew was not subject to Royal Navy standards in their untiring efforts to make the mission successful, Bingham somewhat churlishly recorded on 28 February 1946 when at Marguerite Bay that although the crew had ‘a peculiar mentality’ and Sheppard ‘did a very fine job of work, he did not have the control over his crew which he might have had, and which would have made for a smoother running of the whole enterprise.’ Nothing could have been further from the truth; the Colonial Secretary at Stanley wrote to Sheppard ‘H.E. (Governor CARDINALL) read Sheppard’s report with great interest and … congratulates you on the fine work done. At the same time, he would like to convey to your officers and men his great appreciation of their willing cooperation and of their untiring efforts, Trepassey’s help and labours will have contributed enormously to the success of the survey’.

After returning to Stanley on 3 April, and following a brief period disposing accumulated wartime munitions at sea then loading a cargo of molasses in Barbados, Sheppard returned Trepassey to St John’s on 27 July 1946. During the voyage he received notification of the award of an MBE, the result of Andrew Taylor’s suggestion to Governor Cardinall after Base D was established that ‘recognition of efforts are worthy of some tangible acknowledgement. Cool courage and the tenacity of the entire crew won our unstinted admiration’.

With a feeling of dissatisfaction after this second voyage, and increasingly troubled by ill health, including the lingering effect of the broken ribs sustained on the Eagle voyage, Sheppard declined a request to go south again for the 1947 season.

Now under the command of Capt. Eugene Moores BURDEN, Trepassey left St John’s on 21 September 1946 for Stanley via London, leaving Sheppard to continue his sea going career as a local tanker master until he permanently retired in March 1949. Pulmonary fibrosis led to his death on 31 December 1954 and burial in the Church of England cemetery on Forest Road, St. John’s.

Capt. Sheppard is memorialized in Antarctica by Operation Tabarin naming Sheppard Point ‘a point marking the north side of the entrance to Hope Bay’, and Sheppard Nunatak ‘a conical nunatak north of Sheppard Point at the north of the entrance to Hope Bay and Sheppard Point’.

References

Taylor Fonds, University of Manitoba, https://umanitoba.ca/libraries/units /archives/digital/ taylor /index.html

Anthony B. Dickinson, North Ice to South Ice, The Antarctic Life and Times of the Newfoundland ships Eagle and Trepassey,; DRC Publishing, St. John’s; 2016.

Anthony B Dickinson; Maritime Support for Great Britain’s Antarctic Sovereignty Claim: Operation Tabarin and the 1944-45 Voyage of the Newfoundland Sealing Ship Eagle; The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord, XXVI, No. 1 (January 2016), 1-20

Harold Squires; SS Eagle, The Secret Mission 1944-45; Jespersen Press Ltd, St John’s Canada; 1992; ISBN 0-921692-37-4

Comments

Revisions

January 2021 First added to Dictionary

June 2023 Two additional references added