ROCHÉ, ANTONIO de la

fl 1675 from England

discoverer of South Georgia, was born in London, the son of a French father.

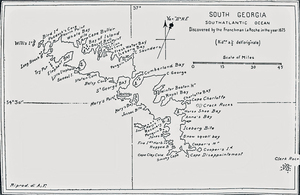

The sole authority for his discovery is a book by the Spanish historian Francisco Seixas y Lovera: Descripción Geográfica y Derrotero de la Región Austral Magallanica. Published in Madrid in 1690, it is based on: 'the description given by La Roché, privately printed in London, in twelve sheets bound in quarto, in the year 1678, and in the French language'. An extensive search has been made for this pamphlet, without success. In 1769 Alexander Dalrymple, an influential chart publisher and historian, published a chart of the South Atlantic, partly based on Seixas's account, on which he depicted la Roché's track and, close to the present position of South Georgia, 'Strait de la Roché', between a small island and a land mass, taken from a map by the Flemish mapmaker Abraham Ortelius in 1586. In an accompanying memoir, Dalrymple described how la Roché, returning from a trading voyage to Peru had been blown eastward from Cape Horn by high winds until he discovered land in April 1675. Here la Roché found shelter in a bay where he remained for fourteen days in sight of snow-covered mountains.

The bay is possibly Drygalski Fjord. Dalrymple added that land was also seen in this vicinity in 1756 by the León, a Spanish merchant ship, commanded by Gregorio Jerez. She had been carried eastward from Cape Horn in a storm during a voyage from Valparaiso to Spain and had sighted a small island and then more extensive land in 54°50'S, which corresponds with the latitude of South Georgia. COOK had Dalrymple's chart and memoir on board the Resolution during his second voyage, which encouraged him to search for la Roché's Strait, resulting in his rediscovery of South Georgia.

Further details of la Roché's voyage, taken from Seixas's account were published in 1813 by Captain James Burney in his authoritative A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Seas, published in five volumes between 1803 and 1817. La Roché sailed from Hamburg in 1674 in a vessel of 350 tons, accompanied by a bilander (a small two-masted merchant vessel) of 50 tons. On his return voyage la Roché called at the island of Chiloe to careen the two vessels and to take on provisions for their return to Europe. After the discovery of land, now identified as South Georgia, la Roché, according to his track on Dalrymple's chart steered due north and 'discovered' in 45°S a very large and pleasant island, where he remained for six days before continuing his voyage to Rochelle, where he arrived on 29 September 1675. This island, named Isla Grande and depicted on charts for many years, does not however exist. Burney points out the difficulties, conjectures and doubts which have arisen respecting la Roché's discoveries.

Rupert Gould, a naval historian, in discussing the mystery of Isla Grande in 1928, pointed out that it was not necessary to write la Roché down as a liar, since he may have thought quite sincerely that he had discovered a new island when he had in fact encountered a part of the South American mainland, where in approximately 45° there are two projecting headlands which could easily be mistaken for an island. If this was the case, then la Roché's longitude was considerably in error, which leads one to question the authenticity of his discovery of South Georgia.

The highest peak on Bird Island, off the north-west tip of South Georgia, was named Roché Peak by the United Kingdom Antarctic Place-Names Committee in 1960.

Editorial comment: Lyubomir Ivanov writes:

I am writing to you in connection with the publication The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (including South Georgia) edited by you, more specifically referring to its Roché entry by Andrew David.

In particular, it narrates: “Rupert Gould, a naval historian, in discussing the mystery of Isla Grande in 1928, pointed out that it was not necessary to write la Roché down as a liar, since he may have thought quite sincerely that he had discovered a new island when he had in fact encountered a part of the South American mainland, where in approximately 45° there are two projecting headlands which could easily be mistaken for an island.”

However, the idea that La Roché might have taken some Patagonian cape for Isle Grade was put forward a good century before Gould by James Burney. (Further details could be found in the attached popular article on Anthony de la Roché.

External links

See: Lyubomire Ivanov; Antonio de la Roche

References

For more information see: Antonio de la Roche

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 Photograph added

December 2019 One additional illustration added

May 2024 One editorial comment added; One external link added; one reference added