MUNRO, HUGH

1873 -1938 from New Zealand

New Zealand agriculturalist, was born on 12 December 1873. He began employment with the Department of Agriculture in New Zealand in April 1897 and worked in both the Wellington and Auckland areas, gradually rising through the ranks of the department until 1924 when he was appointed principal inspector of stock in Auckland. He was a highly experienced government officer by the time he was sent to the Falkland Islands at the request of Governor MIDDLETON.

He soon developed a close working relationship with the Governor, who was very gloomy about the state of the main industry of the Islands as were a number of leading farmers. Munro's Report, published at the end of 1924, was the first truly systematic examination of the condition of the natural resources of the Falklands, and how they might be more effectively managed and exploited. To accompany it, Governor Middleton wrote a long and comprehensive memorandum on the sheep farming industry. Munro never challenged the assumptions of his time underlying the open ranching style of monocultural sheep farming. But he sought to improve farming efficiency, and make the natural environment serve a better-managed sheep farming industry. His report began by stressing the importance of indigenous plants and noted that 'great diversity of opinion still exists on essential points in connection with pasture management among capable men who are in charge of various stations.'

The report noted damage caused by over stocking and the uncontrolled burning of grass: 'The process of decay has been so gradual, and spread over such a long period, that serious concern has only arisen in recent years.' Munro believed that overstocking reduced the overall carrying capacity of the land. As regards Tussac Grass, his words are stark: this 'can probably be classed as one of the most nutritious grasses in the world' so it was 'quite remarkable to see it so much neglected in a country where nutritious vegetation of any kind is all too scarce'.

Munro asserted that the Islands had been overstocked for at least thirty years prior to his arrival. While some land had been well managed, unfortunately the best land had suffered the greatest damage from burning and overstocking. The Report clearly outlines the damage caused by burning and Munro concluded: 'There are no doubt occasions when coarse vegetation on wet camp reaches a stage when burning is justified; but it should be confined to wet camp and resorted to even there only when considered essential and under the most favourable conditions'.

Munro stated that the most effective method of improving the situation was a threefold combination of greater subdivision of the land, reduction of the number of stock carried and a greatly restricted grass-burning regime. Greater subdivision of paddocks would allow a better rotational system of grazing. Munro suggested that the use of lime and clovers would increase the quality of animal fodder.

With regard to the use of cattle in land management Munro advised that:

It would be very beneficial to pastures to carry many more cattle than is done at present, more particularly on properties which are subdivided into areas which will enable them to be used to the best advantage as scavengers to clean up the coarse vegetation as well as for the purpose of consolidating the surface soil.

The reasons for high level of mortality of young sheep were outlined; Munro contended that the main reason was the exhaustion of the pastures, and the poor nutritional value of the remaining vegetation. Natural deficiencies in the soil can be compensated by the provision of rock-salt blocks called 'sheep licks.' Munro criticised rough handling of the sheep by some shepherds, and the failure of some farms to reduce sheep mortality by bridging creeks and ditches. He was scathing about the sheep breeding he observed during his travels in the Islands, and he urged investigation into the value of several breeds of sheep - especially the Corriedale, Merino and Romney. He warned against the danger of indiscriminate inbreeding.

Munro made detailed comments on the quality of wool that the Islands produced. On the quality of farm maintenance, Munro remarked:

With very few exceptions, most of the things that matter in the way of permanent improvements on the stations were done by the pioneers of the sheep-farming industry during the period of 1860 and 1890, and those who have been responsible for the welfare of the industry since have not only failed to carry on the work of development at a normal rate, but they have actually failed - some woefully - to maintain that which was accomplished for them.

One of Munro's most significant recommendations was that an experimental farm should be established as soon as possible near Green Patch settlement, with a small stud flock of sheep and a herd of stud cattle. Their progeny should be sold and used to raise the quality of stock in the colony. This experimental farm could also investigate re-grassing methods, the growing of fodder crops, good practice in the management of cattle and sheep, the draining of waterlogged land, and more modern methods of providing shelter for sheep. He urged that all farms institute a proper system of farm accounting and the keeping of stock records. Munro's final recommendation was that farmers in the Islands organise themselves into an association to take joint decisions about matters of mutual interest.

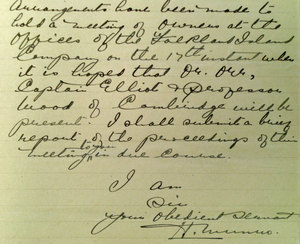

After eight months, Munro returned to New Zealand. On his way home he met the Board of the Falkland Islands Company in London, on 8 January 1925. They unanimously resolved to thank Hugh Munro for his work, but rejected his assertion, as far as the FIC's farms were concerned, that overstocking caused pasture and stock deterioration.

At a meeting of the LegCo on 29 July 1925 it was resolved that: 'The establishment of the Government Experimental Farm, recommended by Mr Hugh Munro in his report ... was agreed on the motion of the Hon. G J FELTON'. In August 1925 the Experimental Farm was established at Lot 5 on Port Louis Farm. In October 1925, £17,000 was voted to establish the experimental farm, later increased to £24,000. It is also clear from a despatch by the colonial secretary that in addition to under-funding, there was considerable opposition to the project from some established farmers. With the arrival of a new governor - Sir Arnold HODSON - the experimental farm came under critical scrutiny and on 23 December 1927 the Colonial Office acceded to Hodson's request to close it down.

Munro's report and the story of the experimental farm show the difficulty of accomplishing agricultural reform on the Islands. Lack of continuity in leadership is well illustrated by the replacement, after a six-year term, of an experienced governor (Middleton) by a new man (Hodson) with very limited knowledge or experience of sheep farming.

After his meeting with the FIC Board in January 1925, Munro returned to New Zealand, and resumed his work for the Department of Agriculture.

Further details of his life are currently unknown, but the will of a Hugh Munro was proved in 1938 by his widow, Eliza,, and this may mark his death on 30 June 1938.

External links

References

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 Illustration added

September 2019 External link added; reference added

February 2020 Three additional photographs added; one external link added

August 2021 Text amended