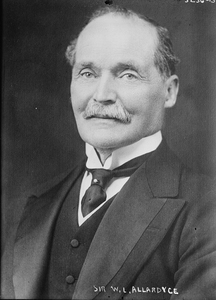

ALLARDYCE, Sir WILLIAM LAMOND

1861 - 1930 from Scotland

governor, was born on 14 November 1861 near Bombay, India. His father was Colonel James Allardyce Ll.D , who served for many years with the East India Company (from 1848 until1887), and his mother was Georgina, née Abbott. The Allardyces were well-known public figures in Aberdeen and were much involved in charitable affairs. William Allardyce was educated at the Gymnasium School in Aberdeen, and also at the Oxford Military College. He was a good scholar and a fine sportsman, excelling at cricket, with both bat and ball

To Fiji

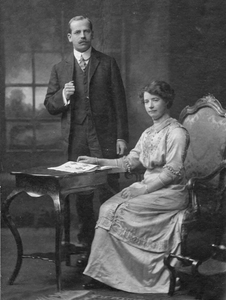

At the age of 18 Allardyce entered the Colonial Service and he was posted to Fiji as clerk and interpreter. During the next 25 years Allardyce occupied almost every position in the Fijian government, eventually becoming receiver-general and colonial secretary. In 1895 he married Constance Angel GREENE at Melbourne, and their two daughters were born during Allardyce's service in Fiji. Both girls were given Fijian names - Viti (later Mrs A Mabutt) and Keva (later Mrs C Butler, who was married in Tasmania in 1923 while Allardyce was serving as Governor). During his period of service in Fiji, Allardyce wrote a number of academic papers on the Fijian language, a history of England in the Fijian language and also a history of the Fijian wars. From 1890 to 1899 he edited a Fijian newspaper called Na Mata. He was instrumental in the decision of the Fijian Government to build a national museum, and when he left Fiji in 1904 Allardyce donated his large collection of Fijian artefacts and books to the Suva Town Hall. This material provided the basis of the national collection. Throughout his life Allardyce collected ethnic artefacts and rare books, and encouraged the establishment of museums.

The Falkland Islands

Allardyce's tenure of office as governor of the Falkland Islands (1904-1915) was a notable period in the colony's history and development. Allardyce has been well described as a 'keen observer and conservator of cultural, historical and natural resources.' The great Swedish scientist Carl SKOTTSBERG, who visited the Falkland Islands in 1911, commented: 'He is warmly interested in the material as well as the spiritual welfare of his colony, and we fully recognised his appreciation of our scientific work, which he tried to promote as far as lay in his power.'

Allardyce's term of office as governor coincided with the advent of the modern era of whaling; the establishment of the Dependencies of the Falkland Islands; the introduction of wireless communication within the Islands and Antarctica and the Battle of the Falkland Islands in 1914. The foundations of the social services of the Falkland Islands were laid; the education and medical services of the Islands were extended - Victoria Cottage Home (a nursing home) was opened, and the King Edward VII Memorial Hospital was completed (among the first patients were casualties from the 1914 Battle of the Falkland Islands). The first Senior School was built and opened in 1907 by Mrs Constance Allardyce; Governor Allardyce personally supervised the construction of the school. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1910, and Allardyce ensured that additional accommodation was provided in Stanley for camp children. At Allardyce's instigation work was begun on a new Town Hall, which was designed to include a library and museum; both these amenities were the result of the initiative of Mrs Allardyce. Testimony of her personal commitment to the Stanley Museum, and of her generous donation of artefacts can be found in the Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper: 'We residents of Stanley cannot be too grateful for the legacy that Mrs. Allardyce has given us'.

When news of the death of (now Lady) Constance Allardyce in 1919 reached the Falkland Islands, the Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper reprinted part of an eloquent tribute that had been made in the Nassau Guardian on 26 November 1919:

The welfare of the young and the relief of the suffering have always been of outstanding interest to her, and in the Falkland Islands she started the Girl Guide movement and introduced the work of the St. Johns Ambulance Association, herself being many a time the means of relieving the suffering and saving life in the outlying homes of the shepherds, miles away from the nearest doctor ... With fine mental equipment and being a great reader with a very retentive memory, Lady Allardyce was also interested in scientific pursuits, and in this direction her discovery of a complete specimen of a Trilobite in the Falklands where previously even Darwin had discovered only traces, and the find of a unique land shell, named in her honour Diaphorostoma allardycea, stands to her credit. She also furnished shells to several museums ... Lady Allardyce excelled as a horsewoman and as an all-round athlete ... Prior to her marriage she was a Sunday School teacher and throughout her life the ideals of Christian character guided her activities and service.

During Allardyce's term as governor the first effective sanitary system for Stanley was built, and street lighting on Ross Road was installed. A public telephone exchange was established. The Boy Scout movement began in November 1912 under Allardyce's direction and patronage. Radio communication with navy ships and with the mainland of South America was established.

Although sheep farming was the dominant economic activity of the Falkland Islands, Allardyce was concerned about excessive dependence upon the wool industry and he urged the establishment of secondary industries.

South Georgia and Whaling

With Captain Carl Anton LARSEN's arrival on South Georgia in 1904 the modern era of whaling began. From the beginning of this new industry Allardyce was insistent on control and regulation. He was responsible for the drafting of the Ordinance to regulate the Whale fishery 1906. (This Ordinance also protected seals, penguins, and some other species of birds). The Ordinance required all whaling expeditions to call at Stanley en route south to the whaling grounds to collect a licence; it also required whaling factory ships to embark a customs officer, and to restrict catchers to two vessels per floating factory ship. Further Whaling Ordinances were enacted in 1908 and 1911.

Before the advent of Southern Ocean whaling almost nothing was known in the Colonial Office about South Georgia; in the early days there even appears to have been some confusion about the rightful ownership of, and sovereignty over, the Island. Whaling removed any doubts as to its value. Allardyce soon realised the importance and worth of South Georgia as a base for whaling, and its potential for raising revenue for the Falkland Islands economy - which was in a parlous state. Despite the excellent financial prospects of whaling for the Colony, and his determination to regulate the industry, Allardyce was well aware of the history of destruction on the northern whaling grounds, and the future possibility for the Southern Ocean whale stocks: 'that in a few years at the present rate of catch there are likely to be very few whales left in that region.'

Allardyce was also deeply concerned about the remaining stocks of fur seals which had suffered grievously since hunting began in the late eighteenth century. In a confidential despatch of 1909, to the secretary of state for the colonies, Allardyce revealed his concern for the conservation of the remaining fur seals, and of the parlous state of the rookeries:

Considering how small they are and the limited number of seals on them at the moment ... if things are permitted to remain in the unsatisfactory condition in which they have been in for many years past, the result is almost certain to be the absolute depletion, if not the entire extermination, of the Fur Seal in and around the Falklands, and the loss to Government of what, if properly managed, would prove in a few years to be a valuable source of revenue ... I have merely to refer you to my Confidential Despatch of 29 December 1908, containing particulars of a raid on the Fur Seal rookery at Volunteer Rocks, almost within sight of the seat of Government. On that occasion the rookery was depleted and the seal pups left to die ... When the rookeries are properly protected it is probable that the number of seals will increase rapidly.

On 25 August 1909 Allardyce left Stanley in the steam whaler Swona to inspect the newly-erected whaling factory at New Island belonging to SALVESEN. Seventy people were employed at the whaling station - including the crews of whale catchers and two large steamers. In a despatch sent to the Colonial Office after his return from his visit Allardyce discussed the colony's natural resources and his concern that some landowners would not face up to their responsibilities for the sustainable development of the Falkland Islands:

The Colonists are non-progressive, and not unnaturally perhaps are perfectly satisfied with a sheep farming investment which has given a return of late years of over 30%, and permits them after a few years spent in this Colony to retire and live in a substantial competence in the Old Country, and join the band of absentee owners ... Needless to say such action does not make for the development of the country or its progress, but permits them in great measure to evade their responsibilities to the Colony in which they have made their fortunes.

At some point towards the end of 1910 Allardyce became alarmed at a discussion which was taking place in the Colonial Office about appeasing Argentine claims to sovereignty. On 24 December 1910, in reply to a secret despatch from London dated 11 November 1910 about the possible cession of the South Orkneys to the Argentine Republic, Allardyce strongly opposed the proposal on the grounds of the financial consequences for the Islands, as well as being: '... almost certain to be misunderstood in South America, and might hereafter form an unfortunate precedent for other demands, and be used to materially weaken our claim to possessing any territory in these seas.'

Conservation

As part of his strategy to avoid wastage Allardyce promulgated new whaling regulations on 6 February 1911. Allardyce insisted that whale carcasses be fully utilised, and that the number of catchers per factory ship be restricted. These restrictions were often made in the face of opposition from the whaling companies and from the Colonial Office. In his budget speech of 1911 Allardyce outlined his conviction that natural resources should be used wisely and not wasted. 'The policy of this Government will continue to be that of endeavouring to establish a permanent industry rather than the rapid collection of a large revenue.' Separate licences were to be issued for South Shetlands, South Orkneys and the Falkland Islands, allowing one floating factory and two whale catchers per licence to operate. Allardyce hoped that the use of floating factories would end the 'strip and dump' attitude. The regulations permitted no more than ten licences to be issued for South Shetlands. South Georgia licensing continued to be arranged separately. Constant vigilance was required on the part of the regulators. On 10 May 1911 the customs officer who accompanied the Sobraon expedition drew attention to the excessive waste of carcasses after the blubber had been flensed off and the oil removed. This report prompted Allardyce to permit licencees to build a shore processing factory on Deception Island - despite the shortness of the season (four months) - so as to use the whole carcass of the whale. Government whaling inspectors and magistrates were soon appointed to monitor the whaling companies' activities.

Allardyce sent James Innes WILSON as stipendiary magistrate to administer South Georgia in 1911; Wilson was also to oversee the developing elephant sealing industry. The sealing quotas proved remarkably well-judged; the 6,000 annual quota remained unchanged until sealing ceased in 1964, except between 1947-52 when it was unwisely increased.

Although he granted the whaling companies licences for floating factories, Allardyce clearly preferred land stations. With the technology then available floating factories were unable to utilise the whole of the carcass, and: 'The floating factory allows the unscrupulous to flense the blubber ... and get rid of the rest by simply cutting it adrift ... Land stations improve utilisation and make supervision more practicable.'

Allardyce's solution to this problem was to have the floating factories working in conjunction with shore stations. In practice, however, the magistrate at South Georgia constantly complained about how poorly even the land-based whaling companies carried out the utilisation requirement in their leases. At one stage Allardyce considered repossessing the leased land if the companies did not improve the utilisation. He felt that there was clear evidence that companies were catching more whales than they could dispose of, and also that whole whale carcasses were being handed over by licensed companies to unlicensed 'processing companies.' 'When not under the eye of the Magistrate ... who is to know whether flensed carcasses only or whole carcasses are used?' The real problem of enforcement was that there was only one government official for the seven whaling stations, which were widely scattered on the northern coast of South Georgia. The magistrate's problems were compounded by the fact that his only means of transport was provided by the, often offending, whaling companies.

As a result of Allardyce's desire to provide greater control and monitoring, Grytviken in South Georgia and Port Foster at Deception Island were designated 'ports of entry' in 1912, and customs officers and magistrates appointed.

Allardyce was well aware of the financial benefits which whaling brought to the Falkland Islands. The income from the whaling industry became increasingly important as the opening of the Panama Canal reduced passing shipping and the considerable income from ship repair.

During the latter part of 1911 the industrious Allardyce began to show signs of understanding the limits of his power and authority: 'Until such time as there is an international agreement on the subject little practical protection can be afforded to the whale.' By September 1911 he is clearly aware of the fate which awaited the whales of the Southern Ocean and the potential consequences of their demise for the colony:

I am not unmindful of the probable transient nature of the whaling industry around the Dependency, and the need to secure for this Colony, whilst whales are plentiful, a substantial balance to compensate for the lean years which are sure to follow later ... of the stagnation of the Colony prior to the advent of the whaling boom you are aware ... the Government was under continuous obligation to the Falkland Islands Company ... I cannot too strongly urge that provision be made for still further strengthening the accumulated assets of the Colony against a possible collapse of the whaling industry during the next decade.

But in 1914 the exigencies of a wartime economy overrode all the previous careful management of the Colonial Office and the cautious conservationist approach of Governor Allardyce. Whale oil became of great importance as a source of glycerine for the making of explosives, government restrictions were relaxed, and the number of whale catchers allowed at South Georgia was temporarily increased to thirty-two. The Falkland Islands and Dependencies were fortunate to have a governor of the calibre of William Allardyce at a crucial period in their history when the whaling industry was expanding at its fastest rate. Some commentators however, mainly Norwegian, are not so complimentary about Allardyce. Tønnessen's comment is typical:

He had shouldered the main responsibility for the administration of this development, which had imposed a tremendous burden of work to which he had not been entirely equal. According to his successor, W. Douglas YOUNG, Allardyce left his office in a state of near chaos: a large number of decisions had been made orally, without reference to the Colonial Office or without being duly recorded. He had gradually adopted an attitude of opposition to the Colonial Office, and felt that he had not been given due credit for his services ... He failed to understand that whaling also had political consequences, and that regulation of it, and the question of sovereignty in the Antarctic, were bound to become international problems.

This assessment is not entirely fair or accurate. The antipathy of some Norwegian historians stems from Allardyce being perceived to be constantly restricting the operations of the whaling companies, and because he appeared to favour British interests. Other Norwegian historians have recognised Allardyce's positive contribution. 'He was in many respects a man ahead of his time when it came to the management of the whale resources.'

The weakness of concentrating purely upon regulation to control the use of natural resources is clearly revealed in the story of Governor Allardyce. Despite his good intentions, the greed of the sealers and whalers and the activities of poachers constantly undermined the regulatory system.

War and Battle

Towards the end of his period of service in the Falkland Islands all of Allardyce's abilities were tested to the full during the Southern Ocean naval crisis, at the outbreak of World War I, from August to December 1914. Allardyce was able to manage the crisis efficiently because he had the wireless station which he had been instrumental in building on the Falkland Islands. Within ten days of the outbreak of war Allardyce learnt that two German steamers, the Rhahotis and the Memphis, were in the vicinity of the Falkland Islands, with 2000 reservists on board. Fortunately the raiders did not attack the Falkland Islands. Allardyce ordered the internment of German nationals on the Falkland Islands, and he strictly controlled the flow of information leaving the Falkland Islands via coastal shipping. Allardyce's next anxiety was the activities of the German cruiser Dresden - which was expected to attack the Falkland Islands in order to destroy the wireless station. Elaborate defensive measures were ordered by Allardyce - including direct telephone communications from various lookout positions to the governor's office and bedroom. There were a number of false alarms, and each time Allardyce rushed to bury cipher books and other various secret papers in a specially prepared place in the Government House peat shed.

With the arrival of Admiral CRADOCK and his squadron (including Good Hope, Glasgow and Monmouth) Allardyce found both an ally and a good friend, but he soon realised that Cradock's ships would be outnumbered and outgunned by the German squadron operating off the western coast of Chile, and there was a possibility, if Cradock were defeated, that the Falkland Islands would be invaded. Allardyce invited the Executive Council to issue a public notice advising women and children to leave Stanley for safer areas in the Camp. The order was issued and within two weeks the evacuation was complete.

Cradock's ships left the Falkland Islands on 23 October 1914 and on 1 November - off Coronel, on the Chilean coast - Good Hope and Monmouth were sunk with all hands. Allardyce now feared the worst, and made plans to withdraw, with his staff, to Mount William. He ordered the Treasury to burn all paper currency and bury the bullion. After some sleepless nights, and a few false alarms, Allardyce was relieved to see a powerful British naval squadron, under the command of Admiral STURDEE, arrive in the Falkland Islands. The ships arrived just in time, because the next day lookouts on Sapper Hill reported that five German cruisers, under the command of Admiral von SPEE, were steaming towards Port Stanley. The first shots were fired on 8 December 1914 by the Canopus which was in Stanley harbour. In the ensuing battle most of the German ships and their colliers were sunk. Subsequent interrogation of prisoners of war revealed how accurate Allardyce's assessment had been. The German intention had been to destroy the Wireless Station and to demand the unconditional surrender of the Colony. Failure to surrender would have resulted in a large force being landed and Stanley was to be razed to the ground. It gave Allardyce particular pleasure in his correspondence after the battle to note that 'throughout this extended period 5th August to 19th December our small 5kw Wireless Station, which I had such great difficulty in obtaining and erecting, covered itself with glory.'

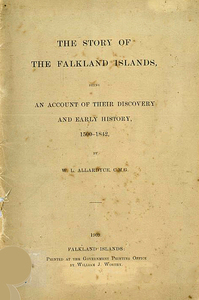

Allardyce sometimes found scant support for his policies from the Colonial Office. Heyburn comments, for example, that his attempts to restrict the number of whale catchers were not well received in London: 'unfortunately, the Colonial Office refused to go along with such strong medicine.' Henry Heyburn rightly described Allardyce as a pioneer Antarctic conservationist; a man of 'broad intellectual interests, tough minded resolution and ready wit. Allardyce's interest in the history of places where he worked is illustrated by the fact that he published a slender monograph (printed in Stanley in 1909) entitled The Story of the Falkland Islands 1500-1842 which is 'effectively the first summary account of the discovery and the early settlement of the island.'

One of Allardyce's last acts as governor of the Falkland Islands was to present a collection of portraits of explorers to the Falkland Islands Museum, and of governors and administrators to Government House. His most visible memorial is the Allardyce mountain range in South Georgia. A harbour on South Georgia is named Allardyce Harbour; Cape Constance and Mount Constance, in South Georgia, are named after Allardyce's first wife.

Later Postings

Allardyce served as governor of the Bahamas from 1915 until 1920 where he continued his wide-ranging cultural and philanthropic interests. Lady Allardyce was very active in war work and she was one of the first recipients of the OBE. She died suddenly on 23 November 1919. In 1920, when he was in San Francisco, Allardyce married again. His second wife was Mrs Elsie Elizabeth Goodfellow, the daughter of J F Stewart of Dundee, and the widow of Adam Goodfellow from Edinburgh.

Allardyce became governor of Tasmania in 1920, but his tenure of office was a short one because he found that he could not live on the salary of £2,750. In his obituary in The Times, it was noted that he had: 'never heard of a King's representative in any state or Crown Colony who had to maintain his kitchen garden out of his own pocket.' And again: 'if the Colonial Office had no further use for his services, he would settle in England and amuse himself with fly-fishing and cricket'.

In 1922 Allardyce moved to his final appointment as the governor of Newfoundland (1922-1928). During his term of office the Labrador boundary dispute between Newfoundland and Canada was resolved. Allardyce took a keen interest in forestry and was an enthusiastic salmon fisherman. Lady Allardyce started the Girl Guide movement on Newfoundland. She also founded an organisation, called the Outport Nursing and Industrial Association, which was responsible for sending fully trained nurses, and other medical staff, to remote rural settlements. Both Allardyce and his wife were committed to practical social action in an attempt to deal with the deep-seated social problems of Newfoundland.

Allardyce was awarded the CMG in 1902; he was knighted (KCMG) in 1916 and advanced to GCMG in 1927. On 30 May 1916 Sir William Allardyce and his wife were appointed a Knight and Lady of Grace of the Order of St John. In 1929 St Andrews University awarded Allardyce an honorary LL D.

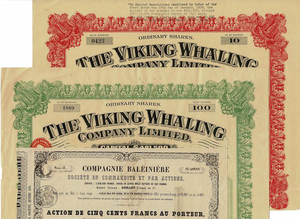

Shortly after his retirement Allardyce was (briefly) the Chairman of the Viking Whaling Company. He died on 9 June 1930, and is buried in Eversley Parish Church, Hampshire. Allardyce's second wife was awarded the CBE in 1945 and died in 1962.

Allardyce's official correspondence can be found in the National Archives, Kew. Copies of his official despatches during his tenure as governor of the Falkland Islands can also be found at the Scott Polar Research Institute. Lady Allardyce donated thirteen volumes of scrapbooks and press cuttings to the Royal Commonwealth Society in 1942, in response to appeals for gifts to restore the Library after war damage. These are now held at the University Library in Cambridge.

Editorial comment: The Allardyces were keen collectors of ethnic art and objects - especially during their time in Fiji. The British Museum houses a collection of 56 related objects donated by the couple. See: British Museum - objects donated by the Allardyces

External links

See: WWI - Events up to and after Battle of Falklands Nov-Dec 1914 - G17.pdf (copies of Allardyce's despatches to Colonial Office in London)

References

Henry Heyburn; 'Profile William Lamond Allardyce, 1861 - 1930'; Falkland Islands Journal; 1980

Ian Hart; Austral Enterprises; Pequena Press; 2020; p23ff

Dr Phil Stone; 'Mrs Allardyce and the Trilobite'; Falkland Islands Journal; 2009

The Story of the Falkland Islands by W L Allardyce - 1909.pdf

Comments

Georgina Ferguson

2018-05-24 03:09:36 UTC

Hello, I am a descendant of Sir William Allardyce and Constance Angel Greene on the family side of my mother Fairlie Ferguson, (nee Butler) and her mother, Keva Butler (nee Allardyce). The article has mis-spelt Keva's sisters name, and should be written as 'Viti' (not Vita). Viti Allardyce was my God Mother.

Kind regards, Georgie Ferguson

Stephen Palmer

2018-07-11 16:06:10 UTC

Thank you for your information about the correct spelling of the name of one of Allardyce's children. The sources in the Falklands use both spellings of your godmother's name! The correction has now been made.

Revisions

2018 - Correction to text

June 2019 Five photographs added

July 2019 Minor correction to text; references and external link added

September 2019 References added; external links added

January 2020 Two additional photographs added

September 2020 Editorial comment added

January 2021 One additional photograph added

March 2021 One additional reference added

July 2021 Five additional photographs added

November 2022 Text amended

January 2023 Text corrected