STURDEE, Sir FREDERICK CHARLES DOVETON

1859 - 1925 from England

admiral, was born into a naval family on 9 June 1859 at Charlton, London SE.

His father was Captain Frederick Rannie Sturdee RN and his mother Anna Frances the daughter of a Colonel Hodson, the marriage taking place on board HMS Waterwitch at St Helena. He was educated at the Royal Naval School, New Cross, before entering the Royal Navy at the age of 12 on Britannia. A midshipman at 14, Sturdee was promoted to full lieutenant before his 21st birthday, specialising in gunnery and later as a torpedo officer during service in the Mediterranean, North America and the West Indies.

His career continued its unabated progression through to the outbreak of war in 1914 when he was Chief of Naval Staff under the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg. At this point Sturdee's career was thrown in doubt by two events, first the resignation of Lord Louis because of his supposed German connections and second, the naval defeat at Coronel off the west coast of South America. Prince Louis was succeeded by Lord Fisher who despised Sturdee, probably because of an earlier peacetime clash between Fisher and Admiral Beresford in which Sturdee supported Beresford under whom he had previously served.

The defeat at Coronel, which resulted in the loss of HMS Good Hope, Admiral CRADOCK's flagship and HMS Monmouth, was the first sustained by the Royal Navy for over a century. Fisher blamed Sturdee for the defeat which was, however, surrounded by controversy. Admiral Graf von SPEE's German East Asiatic Squadron, which inflicted the defeat, was based at Tsingtao, China, at the outbreak of war in August 1914 and was ordered to proceed to the Pacific although one of his ships, the Emden, was detached to attack Allied shipping in the area, which it did very successfully. Von Spee's remaining squadron comprised the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst (the flagship) and the Gneisenau and the light cruisers Nurnberg, Leipzig and Dresden. The ultimate destination of the squadron was the west coast of South America where there was a strong German presence and much pro-German sentiment.

The British naval presence in the area was limited and mainly comprised ageing and obsolete warships, the old battleship Canopus which was unreliable in operation and slow in speed, the obsolete cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth and the modern light cruiser Glasgow. The low priority given to the area stemmed from the need to spread British naval presence over vast areas to counter the threat to Allied shipping perceived as resulting from any break-up of the German squadron into independent units as occurred with the Emden. A scheduled detachment to Admiral Cradock of an effective warship was thus cancelled. Late in October 1914 Cradock sailed from Port Stanley with his flagship Good Hope, Monmouth, Glasgow and the armed merchant cruiser Otranto, having made known in the Falklands that he did not expect to survive the battle he anticipated would ensue. What is not clear is whether he was then fully aware of his terms of engagement authorised by the Admiralty which required him to engage the enemy only with the support of the Canopus which, predictably, was again deemed to be unseaworthy with engine trouble. In the event Cradock met and engaged off Coronel, Chile, on 1 November 1914 von Spee's squadron of five modern warships manned by experienced professional seamen. Cradock detached the Otranto from the battle because of its ineffectiveness and the only other survivor was the Glasgow whose superior speed proved vital. Good Hope and Monmouth were lost with all hands, a savage blow to British naval prestige.

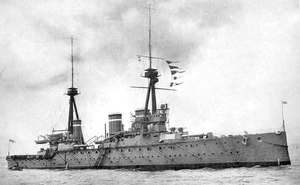

This was the situation faced by the Admiralty in London with Sturdee, to his credit, advocating the detachment from the Grand Fleet of fast capital ships to form the backbone of the squadron needed to avenge Coronel though this was initially opposed by Admiral Jellicoe. However, a firm decision was made by Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, and Lord Fisher, First Sea Lord, to detach the fast, powerful battle cruisers Inflexible and Invincible to form the nucleus of the British squadron and to join up with Admiral Stoddart's cruiser squadron at the Abrolhos Rocks off the Brazilian coast. Time was of the essence and when it was reported that both battle cruisers could not be made ready to sail before Friday 13 November Churchill issued an order under his own hand directing the ships to sail on Wednesday 11 November with a proviso that if work on them had not been completed the workmen must travel on the warships and be repatriated as and when opportunity arose. The significance of this decision will be seen later.

It remained for the commander of the squadron to be appointed. Fisher's dislike of Sturdee had led him to inform Churchill that he could no longer serve with Sturdee as his chief of staff. Churchill's response was to appoint Sturdee, who had been promoted to vice-admiral in December 1913, as commander-in-chief South Atlantic and Pacific with his objective the destruction of von Spee's squadron. This was an effective solution to the personal problems besetting Fisher and Sturdee which had not been eased by Sturdee remarking that he had originally proposed the detachment of capital ships. The clashes of personality between senior figures again surfaced at the Abrolhos Rocks when Captain John Luce of HMS Glasgow, anxious to sail to the Falklands and to avenge Coronel urged Sturdee to advance his sailing date for the Falklands. A somewhat surprised Sturdee did, in fact, do so by one day, another highly significant decision.

The British squadron arrived in the Falkland Islands on 7 December 1914 and commenced coaling, initially of Bristol and Glasgow. At this stage defence of the Islands was limited to the old battleship Canopus which, following the defeat at Coronel, had been alerted by Glasgow at sea and had sailed back to Port Stanley but stopped only briefly. She was, however, ordered back to the Falklands to act as guard ship with her 12 inch guns, only to cause alarm and consternation among the population when her smoke was seen and thought to be from the German squadron.

Coaling was incomplete when the following morning lookouts on Sapper's Hill sighted the approaching German ships and alerted Sturdee who calmly finished dressing and took breakfast. The vanguard of the German squadron comprised the armoured cruiser Gneisenau and the light cruiser Nurnberg and their immediate reaction to receiving a salvo from the concealed Canopus has intrigued naval strategists ever since.

It was a very fine day with excellent visibility which meant that once the British squadron was out of the harbour and in pursuit of the German warships the result was not in doubt. It is argued therefore that the best opportunity for Admiral von Spee was to use his surprise arrival to attack in the confined waters at a time when the British warships were coaling and two of the cruisers had engines under repair. Von Spee, however, ordered immediate withdrawal once the distinctive masts of the battle cruisers had been observed. His available intelligence was below normal standards because the arrival of the battle cruisers was known to German interests on the east coast of South America but the news had not reached von Spee. His captains were not all in favour of an attack on the Falklands and if the Islands had been bypassed it is possible that he could have broken through to his home port. The German squadron had also been delayed by bad weather rounding Cape Horn which had resulted in loss of coal reserves being carried on deck.

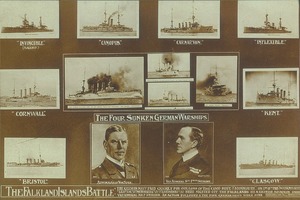

Of the five German warships four were sunk, the only survivor being Dresden which remained a potential threat until the following March when she too was sunk. Over 2,300 German naval seamen were lost whereas the British losses were in single figures. The success fully restored the Royal Navy's standing and brought widespread acclaim to Admiral Sturdee but Fisher believed that his tactics were flawed and that Dresden should not have escaped. von Spee was, however, an outstanding tactician and at times outmanouvered Sturdee; but the British Admiral was also an able commander and tactician and used his advantages in speed and range to the full. He had also anticipated that von Spee might sacrifice his two armoured cruisers in order to give the light cruisers a chance of escaping. If anyone was to blame for the escape of Dresden it might be Captain Luce of Glasgow whose diligence in pursuing his immediate quarry to the bitter end might well have been a reflection of his determination to avenge Coronel.

It is generally acknowledged that the victory was the most significant and convincing naval action of World War I and although Fisher attempted to delay his return to the UK, Sturdee arrived to a hero's welcome and was fêted everywhere he went. He was created baronet and awarded a grant of £10,000, a substantial sum in those days. He was befriended by a grateful King GEORGE V and this stood him in good stead in his continuing conflict with Fisher which had flared up following an acrimonious exchange of cables after the battle.

Given the critical time factor, Sturdee was a 'lucky admiral' for a number of reasons. Churchill had advanced the date of departure of the Invincible and the Inflexible by two days. Any delay would have been disastrous, particularly for the Islands. Churchill had used Sturdee's appointment as C-in-C to resolve a dispute with Fisher. On the voyage south, Captain Luce urged Sturdee successfully to advance the date of sailing from the Abralhos Rocks (Luce reminded Sturdee of this following the action and received the same frosty reaction as Sturdee himself had received from Fisher in relation to the battle cruisers). The German squadron's arrival at the Falklands was delayed by bad weather and von Spee failed to attack upon his surprise arrival at Port Stanley. Finally the weather on 8 December 1914 was perfect.

Sturdee had, however, achieved his objectives and his career went from strength to strength. Upon his return to Britain he was appointed to command the Fourth Battle Squadron and took part in the Battle of Jutland.

He achieved the ultimate rank of Admiral of the Fleet in 1921.

Admiral Sturdee had but a short retirement, dying at his home in Camberley, Surrey on 7 May 1925 at the age of 66 but not before he had played a major role in the preservation of HMS Victory.

He had married Marion Adelaide Andrews on 23 September 1882 and there were two children, a son, Lionel Arthur Doveton Sturdee (1884-1970) who later became a rear-admiral, and a daughter, Margaret Adela Sturdee who married CM Staveley who also became a rear-admiral.

Their son, William Staveley, (1928-1997) became an admiral of the fleet, a remarkable family achievement of service and devotion for which Britain has much to be thankful.

At Sturdee's funeral which took place at St Peter's Church, Frimley, there were no less than eight admirals as pall bearers, one of whom was Sir Richard Phillimore, the commander of Inflexible at the battle.

Sturdee features in a commemorative stamp set of 1989, marking the Battles of the Falkland Islands and the River Plate.

Editorial comment: The sketch (image 1297) is by the famous marine artist William Wyllie and is held at the Royal Museums Greenwich; ' At 09.00 [on 8 December] the Canopus fired at the two German ships at extreme range from her forward turret but her shells fell short. The guns in her aft turret were loaded with practice rounds for a forthcoming target shoot but she fired them none the less, more to clear the guns rapidly than anything else, and one of them ricocheted off the water and struck the rear funnel of the Gneisenau. At this point the two German ships turned and headed away to rejoin Von Spee's main force. Sturdee at the same time was rapidly raising steam to pursue and, in the subsequent battle later in the day, he sank von Spee's entire squadron, with the exception of the light cruiser Dresden which managed to make good an escape. Canopus was not involved in the chase and only left Port Stanley ten days later, returning to her South American patrol station of the Abrolhos Rocks until she transferred to the Mediterranean early in 1915.'

External links

See: V. W. Baddeley, revised by Andrew Lambert; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

See: Standing up to the Royal Navy - Maximillian Von Spee YouTube video

See: Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee YouTube video

References

For full details of Sturdee's naval career see: Alastair Wilson; A biographical dictionary of the twentieth century Royal Navy - volume 1; Admirals of the Fleet and Admirals; Seaforth Publishing; 2013

Admiral Sturdee's despatch on the Battle of the Falkland Islands; Falkland Islands Journal; 1968

Alfred.-F. Gruene; Battleships Involved in the Battles of the Falklands and Coronel; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014; Mark Connelly; Putting the Falkland Islands on the Silent Screen : the Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands.; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014

Geoffrey Bennet; Coronel and the Falklands; Birlinn Ltd; 1964

Stephen Palmer; A Meticulous Naval Signal – 21st December 1914.; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014

Obituary for Sir Doveton Sturdee; The Times; 8 May 1925

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 two extra photographs added

June 2019 Link added

July 2019 External link added; additional photograph added

August 2019 Two additional external links added; photographs updated

October 2019 Five references added

February 2020 One additional photograph added; one additional reference added

April 2020 One illustration added; editorial comment added; one reference added

October 2020 One additional photograph added