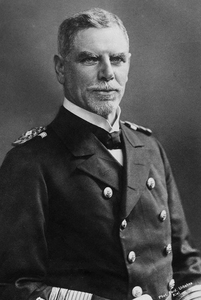

SPEE, MAXIMILIAN JOHANNES MARIA HUBERTUS, Reichsgraf (Imperial Count) von

1861 - 1914 from Denmark (also Germany)

German admiral, was born in Copenhagen on 22 June 1861.

He was the youngest of five sons of Reichsgraf Rudolf von Spee from a Catholic Prussian family and his mother Fernande Tutein was Danish. He entered the Imperial German Navy at the age of 16 as a cadet and thereafter rose inexorably through the ranks as the German Navy expanded to meet the challenges of the Reich's territorial expansion in Africa and the Far Fast. Tall, of military bearing, von Spee was a commanding figure, blue-eyed with wavy hair, bushy eyebrows and a beard.

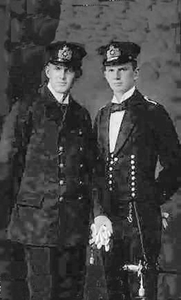

He married in 1889 Baroness Margarete, daughter of Baron von der Osten Sacken of the House of Wangen and they had three children, two sons, Otto and Heinrich, and a daughter, Huberta.

He was made port commander of German Cameroon in 1887/8 and was appointed flag-lieutenant of the Deutschland in 1897, serving in the Far East until 1899. He took part with the international force in suppressing the Boxer rebellion and saw his first action. Later he became involved in weapons development before being appointed chief of staff of North Sea Command in 1908. Made a rear-admiral in 1910 he was appointed to the coveted position of commander of the East Asiatic Squadron in 1912 and promoted vice-admiral.

Life in the Far Fast in the pre-war years was socially demanding but von Spee did not allow this to distract him from his prime responsibilities and he kept his squadron at a high level of competence by vigorous training. The long distance from home necessitated continuity of service and this led to high morale and confidence, crucial factors in his successful move across the Pacific following the outbreak of war when he was pursued by the navies of five nations, Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Russia. Von Spee had detached one of the cruisers from his squadron, the Emden, to wage independent attacks on allied shipping, mostly in the Indian Ocean, which it did very successfully until sunk by HMAS Sydney. It must be said that the initiative was not von Spee's but that of the Emden's captain but nonetheless he made the assenting decision promptly despite wishing to keep his squadron intact. The fundamental problem in moving a naval squadron vast distances in those days was coaling and von Spee managed this brilliantly, staying within international law and yet managing to keep his pursuers guessing his whereabouts.

A British squadron commanded by Admiral CRADOCK, comprising his flagship, the old cruiser HMS Good Hope, another old cruiser HMS Monmouth, the modern light cruiser HMS Glasgow and the armed merchant cruiser HMS Otranto sailed from the Falklands to confront von Spee off the coast of Chile in the Battle of Coronel. They were ostensibly supported by the elderly battleship HMS Canopus but she was slow and unreliable and took no part in the action.

In the one-sided battle Otranto withdrew as she was out of her class and only Glasgow escaped, Good Hope and Monmouth both being sunk with all hands. Cradock is on record as stating at Government House in Stanley that he did not expect to survive the battle with the German squadron. The humiliation of the defeat shook confidence in the Royal Navy at home and led to jubilation in Germany.

There were recriminations with Cradock alleged to have disregarded instructions not to accept action unless supported by the Canopus. He was a brave man and a friend of von Spee's from their time in the Far East together but he was hopelessly outclassed in the range and speed of his ships and the experience and efficiency of the crews.

The Germans had much support in South America and von Spee and his squadron were feted in Valparaiso. Von Spee, however, retained his dignity and was very mindful that his own position remained precarious. At one function a toast was proposed to the damnation of the British Navy but von Spee, ever conscious of the vicissitudes of war and the quality of his opponents, would have none of it and walked out.

In the Islands news of the defeat at Coronel was greeted with alarm. A telegram was received on 6 November 1914 from the Admiralty warning them to expect an attack by the German squadron and instructing them to destroy all stores likely to be of use to the enemy. The governor was convinced that von Spee would wreck the Wireless Station and burn down Stanley.

The Volunteers were mustered and instructed to resist an attack but to remain out of reach of the ships' guns, a seemingly impossible task. Women and children as well as many elderly persons were evacuated, surplus stores removed, papers and records concealed and shipping moved to isolated parts. The Islanders felt defenceless with HMS Glasgow and HMS Canopus ordered to Montevideo to await reinforcements although the latter was ordered back to Stanley as a defence vessel.

Surprisingly von Spee did not sail promptly from the Pacific despite his correct assumption that powerful British forces would be sent to avenge the Coronel defeat. He had replenished his coalbunkers for the long journey home but ran into severe weather rounding Cape Horn resulting in the loss of his coal reserves carried on deck as well as damage to his ships. He considered it fortunate that they encountered the four masted British barque Drummuir laden with coal but the ensuing delay in finding a suitable haven for transferring the cargo and making good the storm damage proved crucial in the forthcoming battle.

Von Spee consulted his senior officers on whether to proceed directly to the River Plate area or to divert to the Falkland Islands to destroy the British naval base there. Although the majority favoured bypassing the Falklands, von Spee ruled against them believing that the destruction of her only base in the area would disrupt Britain's naval power and enhance his own chances of reaching his home base.

In the event, a powerful British squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral STURDEE arrived at Port Stanley on 7 December 1914 and was coaling the following morning when the vanguard of von Spee's squadron was sighted. Ironically, it was the Canopus which fired the first shots in the Battle of the Falkland Islands in which the Royal Navy fully avenged the defeat at Coronel. Four of the German warships were sunk, the only one to escape being the Dresden which was eventually located and destroyed off the west coast of South America. Von Spee put up a brave and valiant resistance but was hopelessly outgunned and the outcome was inevitable although he did make an unsuccessful attempt to save his light cruisers by sacrificing his two armoured cruisers.

Von Spee lost his life in a battle which he had foreseen, remarking when presented with flowers after his victory at Coronel that they would go well on his grave. His two sons also died in the battle, one on the Gneisenau and one on the Nurnberg. The two battles had been fought with great bravery and honour on both sides but with grievous casualties many of which resulted from complying with naval traditions such as continuing to attack stricken vessels because they could not or would not strike their flags.It falls to few leaders to win the respect of both sides in battle. In a little over five weeks Admiral Graf von Spee, Commander of the German East Asiatic Squadron, inflicted upon the Royal Navy at the Battle of Coronel its first defeat in over a century and then, at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on 8 December 1914, suffered an overwhelming defeat and lost his life. Modest and chivalrous in victory, in defeat he displayed the qualities of a great leader with bravery, tactical awareness and the unreserved support and loyalty of his men, at the same time earning the respect and admiration of his opponents.

Almost exactly twenty five years later a German pocket battleship named after von Spee, the Admiral Graf Spee, was sunk after a battle off Montevideo on 17 December 1939 by a British flotilla commanded by Commodore HARWOOD. Von Spee featured on a Falkland Islands stamp issued to commemorate these battles in 1989.

Editorial comment; In December 2019 the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust announced that the wreck of the SMS Scharnhorst had been located 98 nautical miles southeast of the Falkland Islands at a depth of 1,610 metres. The expedition was lead by the Falklands-born marine archaeologist Mensum Bound.

External links

See: Standing up to the Royal Navy - Maximillian Von Spee (YouTube video)

References

Alfred.-F. Gruene; Battleships Involved in the Battles of the Falklands and Coronel; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014;

Mark Connelly; Putting the Falkland Islands on the Silent Screen : the Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands.; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014

Geoffrey Bennett; Coronel and the Falklands; Birlinn Ltd; 1964

Stephen Palmer; A Meticulous Naval Signal – 21st December 1914.; Falkland Islands Journal; 2014

Richard Hough; Falklands 1914; the pursuit of Admiral Von Spee; Periscope Publishing; 1980

Michael McNally; Coronel and the Falklands 1914; Duel in the South Atlantic; Oxford, Osprey Publishing; 2012;

Lost Ships - the hunt for the Kaiser's superfleet; with Mensum Bound; DVD; TVT Productions & Polestar Pictures

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 Additional photographs added

June 2019 Link added

June 2019 Additional photograph added

August 2019 External link added; photographs updated

October 2019 Five references added; additional illustration added

December 2019 One additional external link added

February 2020 One additional photograph added; editorial comment added

March 2020 One DVD reference added

April 2020 One additional photograph added; one additional reference added

March 2021 One additional image added