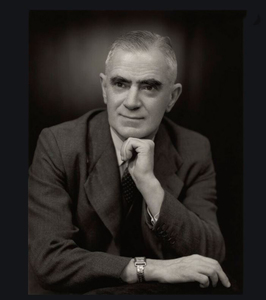

STEWART, (ROBERT) MICHAEL MAITLAND

1906 - 1990 from England

foreign secretary, was born on 6 November 1906 at Bromley, Kent, the only son of Robert Wallace Stewart DSc and Eva, née Blaxley. He was educated at Christ's Hospital Horsham and St John's College Oxford. After a spell as a teacher, he entered the army during World War II, emerging as a captain. He was elected MP in 1945 and when Labour were re-elected in 1964 was appointed secretary of state for education. He married Mary Henderson in 1941.

Stewart was secretary of state for foreign affairs from 22 January 1965 to 11 August 1966 and then again from 16 March 1968 to 19 June 1970. The post became secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs on 17 October 1968 with the merger of the Foreign Office and the Commonwealth Relations Office. On 16 December 1965, UN General Assembly Resolution No 2065 was passed inviting the governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom to 'proceed without delay with negotiations with a view to finding a peaceful solution to the problem [of the Falklands]'. This launched a series of negotiations between the two governments during Stewart's two periods in office. The Argentines had raised their claim with Stewart when he visited Buenos Aires in January 1966 on the first ever visit to Latin America by a British foreign secretary and been rebuffed, although he still had to deny that he had discussed sovereignty on his return. HMG hoped to remove the mixture of government measures and general awkwardness by which Argentina obstructed travel and trade between the Falklands and the mainland.

When George BROWN resigned on 16 March 1968 he left Stewart the awkward political situation following the revelation of the Memorandum of Understanding to Falklands councillors and the brouhaha which followed their telegram to the House of Commons. Stewart was to spend considerable time and effort in the House defending the British Government's position in the ongoing talks between British and Argentine officials, preferring, despite his preoccupations with Vietnam, Rhodesia, the EEC and the Cold War, to come to the House himself rather than send a junior minister. He was aware of Conservative strength of feeling on the Falklands issue, once the Government's negotiating stance had been revealed. In a debate on 26 and 28 March 1968, much was made of Councillors' message. Opposition speakers asked why sovereignty should be discussed at all, if there was no intention to cede it, why there was such secrecy and why the Islanders were not being consulted. Stewart's defence was that, like it or not, sovereignty had to be discussed with the Argentines if there were to be any talks at all, and that talks were necessary both because the UN Resolution required them and to improve Islanders' communications with the mainland. He pointed out that the governor was able to take ExCo into his confidence and that such discussions were more likely to achieve agreement if conducted in secret. The object of the talks was 'to secure that there is a satisfactory arrangement ... only if it were clear to us that the Islanders regarded such an agreement as satisfactory to their interests'. Transfer of sovereignty could only be considered on that basis.

Suspicion was reinforced by rumours of what Lord CHALFONT had said on his visit to the Islands in November 1968. This was reported to both Houses on 3 December, to critical receptions from the opposition. On 11 December a cabinet decision was taken to abandon negotiations on the basis of the Memorandum because of the Argentine refusal to accept that it should contain a statement that a transfer of sovereignty should be subject to the wishes of the Islanders. That day Stewart made a statement in the House about the progress of talks stating that there was 'a basic divergence' over the British government's insistence that no transfer of sovereignty could be made against the wishes of the Islanders but that talks would continue on this basis. He rejected suggestions that there was pressure on Islanders to change their wishes. The exchanges on the Falklands in a wide-ranging foreign affairs debate the next day followed a similar pattern.

Thereafter talks continued without prejudice to each country's position on sovereignty under the 'sovereignty umbrella'* until, on 21 November 1969, letters were sent by the British and Argentine representatives at the United Nations to the Secretary-General stating that 'the two Governments have continued negotiations and that, although divergence remains, special talks will begin early next year to promote free communications and movement in both directions between the mainland and the islands'. Both sides would continue their efforts towards 'a definitive solution to the dispute'. This begged the question of what that would be and once again whether sovereignty should be discussed. Stewart conceded in the Commons that Britain had abandoned the position that sovereignty was not for discussion. When Sir Frederick Bennett said that the Argentines were only interested in improved communications in the hope of a change of heart by Islanders, Stewart replied that it would be 'quite foolish' if, because the Argentines held this view, we sought to prevent improvement.

In his autobiography Life and Labour (1980) Stewart, referring to Gibraltar and the Falklands, wrote:

Some day, some historian may argue that Britain was short-sighted to maintain a running dispute with two important countries for the sake of tiny territories with few inhabitants, the more so as there were no major strategic or economic issues involved... It seems to me, however, that if Britain, or any other country, behaves as if she would do anything for a quiet life no matter what happens to people who have trusted her, this will not create an atmosphere favourable to peace.

Stewart was concerned about the United Kingdom's relations with Latin-America generally and took a considerable interest in trade, but that did not stop him standing up for the Falklands. The Memorandum of Understanding and the commitment to discuss sovereignty which went with it were a difficult hand to play. He appears to have coped as well as anyone could.

Stewart retired from Parliament in 1979 and accepted a life peerage. He died in London on 10 March 1999.

External links

See: Hansard 1803-2015 Michael Stewart's contributions in Parliament

See: Foreign Affairs debate in the House of Commons 12 December 1968

References

Michael Stewart; Life and Labour - an autobiography; 1980

Comments

Revisions

October 2019 Two external reference added; one reference added