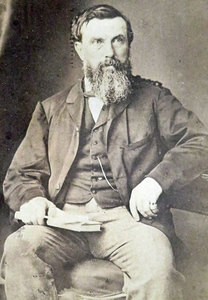

SNOW, WILLIAM PARKER

1817 - 1895 from England

mariner, explorer and writer, was born at Poole, Dorset on 27 November 1817. His father, a naval officer who had served at Trafalgar died in 1826 and his mother, née Barker, took the family abroad, leaving William behind at the Royal Hospital School, Greenwich. At 13 he was apprenticed to a merchant brig bound for Calcutta and experienced the worst excesses of cruelty and discipline at sea. He had an unsuccessful period working in Australia and returned to England in 1836. Snow joined the Royal Navy, found it not to his liking, was a troublesome seaman and was eventually discharged (apparently after jumping overboard to rescue a colleague from a shark) after a year's service off Africa. On his return to England he married and embarked on unsuccessful ventures such as running a hotel in Australia and a club in Italy. He augmented meagre earnings by writing for the papers and acting as clerk and translator.

After a year in America where he became transfixed by the fate of the Franklin Expedition, Snow returned to England in 1850 and persuaded Lady Franklin to appoint him as purser, doctor and chief officer on the Prince Albert in one of many unsuccessful searches for Franklin. Snow did not get on well with his fellow officers, but wrote the official, well received, account and for years afterwards badgered the Admiralty to send him on further expeditions in search of Franklin.

Captain Allen GARDINER, the visionary behind the Patagonian Missionary Society, had planned to establish a mission station on one of the Falkland Islands and purchase a vessel to traverse between there and the coast of Patagonia. The Society eventually was granted a lease on Keppel Island and the 86 ton schooner Allen Gardiner sailed from Bristol in 1854 with Snow in command arriving at Keppel in January 1855.

Snow's journals give a valuable early account of the vegetation of the Falklands before the introduction of grazing stock. The beaches along the north-east coast of Keppel are described a 'being fringed with Tussac, Fachinal and Balsam Bog' and the flat area between Cove Hill and Robinson's Point was covered with 'plentiful Tussac'. On the afternoon of 5 February, the day of the 'official' landing ceremony, Snow allowed the crew and settlers a general holiday. Three of the men wandered up through the main valley on the Island and, despite Snow's repeated earlier warnings, one of them, John Watts, threw a lighted paper on the ground and started a small fire, which quickly spread out of control in the dry grass. The fire continued to spread for several days, particularly all round the slopes of Cove Hill. Eventually it threatened the construction of the small settlement and Snow and his party were forced to move across to the other side of the creek. Snow described his view of the fire just before they made the decision to move the settlement:

before us, the whole valley was one awful mass of flame, all burning bushes with thousands of little dancing fires, were coming with remarkable rapidity towards us ... scores of the globular bog-balsams were glowing with livid fire, while the fachinal and other shrubs crackled in the flames.

During all this, more alarming thoughts were going through Snow's mind concerning the impending disaster that might befall the whole venture, and indeed the whole Society! He recounts:

I knew the state of funds at home, I knew that all was with us ... were our present supply; or even the timber, to be consumed by this terrible conflagration, there would then be an entire stop to the work. Dispirited at hearing nothing but disasters [a reference to Gardiner and his companion's death by starvation off Tierra del Fuego, 3 years earlier], the public would not come forward to assist any more.

Snow and his party dug a firebreak across the narrow isthmus to isolate the piece of land they were on, from the rest of the island and hence the fire.

The following week was spent building a six-roomed house planned as a temporary dwelling, so care was taken to avoid using timber intended for the permanent house. In the event, the party stayed in the house for almost nine months before moving to the site of the permanent station (the present settlement).

The fire took almost five weeks to burn out and only one or two parts of the Island escaped. Watts was eventually taken to Stanley, tried and found guilty of arson. Although he was fined the statutory £20, Snow's appeal on his behalf had the sum reduced.

Snows' journals are of considerable historical value as they contain detailed accounts of the establishment of the mission, his journeys to neighbouring islands, the natural history, and the town of Stanley. In relation to apportioning blame for the fire, once the temporary dwelling was established, Snow took great pains to hand over authority of the station to the doctor and superintendent, Ellis and his 'land party', and from then on regarded them as distinct from his 'ship's party'.

This enabled Snow to write to the Governor on 13 July (from Saunders Island):

As to the destruction by fire of the Tussac and boxwood on Keppel Island I must inform you that neither myself or ships crew, or any person under my authority, have done aught, directly or indirectly to injure any of the land, or material, or prohibited articles on Keppel ... and in relation to the fire (not caused by any of the party under my own immediate control) I will immediately communicate with Mr Ellis, the superintendent of the land party who will no doubt, give you full information on the subject .... As Allen Gardiner, her crew and myself are entirely distinct ... and separate from the land party, in regards to the duties of the missing station .... I shall be considered free from all responsibility or liability as to what may have occurred or may yet occur on Keppel Island.

He goes on to dispel any rumour that the party was interested in moving to Saunders Island, his own presence there being to beach and repair his vessel.

He seems to have been a difficult man to get on with and when the Reverend GP DESPARD arrived on 30 June 1856 to be superintendent, he and Snow differed strongly in their views on how the mission should be run. Indeed Snow was at variance with the Society from the time of his arrival in the Falklands, having firm views of his own on the administration of the station and the missionary effort to South America. On 29 September 1856, soon after Despard's arrival, Snow was dismissed from his command of the Allen Gardiner and was forced to return to England where he continued to appeal against his treatment by the Society for many years. He eventually lost a three year lawsuit and this cost him the profits from his book A Two Years Cruise off Tierra del Fuego the Falkland Islands etc (1857) on the cruises of the Allen Gardiner. His account of the region and the early history of the British colony must be considered his most valuable legacy to the Falklands. A charming painting of Keppel Island attributed to him has been presented to Stanley Museum.

He went to America where he lived near New York, writing and editing books. On his return to England he continued to dwell on the fate of Franklin and the last 20 years or so of his life were spent compiling volumes of indexes, of notes and of biographical records of Arctic voyages. He lived out his last years in poverty, and died on 12 March 1895 at Bexley Heath.

Snow was a man of strong feelings, which he liberally put in print, often landing himself in trouble. He railed against the Geographical Society for many years and Sir Clement Markham in particular. Markham was, however, gracious enough to recount in his obituary of Snow in the Geographical Journal: 'The enthusiast had many good qualities and was grateful for any kindness .... It is a melancholy story, and ... I for one am glad to say all that can be said of good for a brother Arctic'. JK Laughton wrote in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

Snow's unsettled life, his series of enthusiasms (including emigration, telegraphy, early closing of shops, and total abstinence), his disagreement (which spilled into print and the courts as well as into unpleasant accusation) with almost all in authority, and above all his obsession with the Franklin search, suggest mental disorder; and suffering from this he could not achieve success, despite his intelligence, talent as a writer, and skill as a mariner.

He is most honestly summed up by the historian AGE Jones: 'Snow was not a success. But he was a trier after a poor start and many disappointments. Many men would have given up but he kept trying to the end'.

External links

See: William Parker Snow; profile by Ian Stone (1978)

See: Parker Snow and the Franklin relics

See: Full text of Snow's book of cruise off Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Islands

References

William Parker Snow; A Two Years Cruise off Tierra del Fuego the Falkland Islands etc; Longman Brown Green Longmans & Roberts1857

A. G. E. Jones; William Parker Snow, in Falkland Islands Journal, 1979.

Jim McAdam; The Great Fire on Keppel Island 1855; Falkland Islands Journal; 5(3) pp22-28; 1989

Sydney Miller; Patagonian Missionary Society - Keppel Island 1855 -1911; Falkland Islands Journal; 1975

Ian Stone; William Parker Snow 1817–1895, in The Polar Record; Vol. 19 (1978–79), Scott Polar Institute, pp.163–165;1980

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 Photograph added

October 2019 Five references added; four photographs added; three external links added

December 2019 An additional photograph added; one additional external link added

October 2020 One additional photograph added

July 2021 One additional external link added