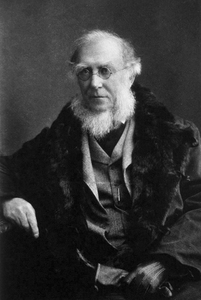

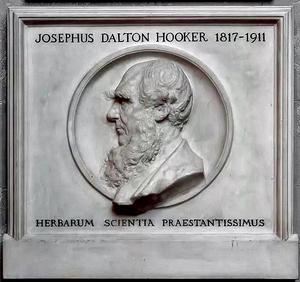

HOOKER, Sir JOSEPH DALTON

1817 - 1911 from England

botanist, was born in Halesworth, Suffolk on 30 June 1817, the son of William Jackson Hooker and Maria Hooker, daughter of Dawson Turner, a Norfolk banker and amateur naturalist. William Hooker stood then at the threshold of a botanical career which would lead to a professorship at Glasgow and the directorship of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. He encouraged Joseph Hooker's latent interests in natural history but Joseph was indebted to both parents for his artistic talent. After attending the grammar school in Glasgow for three years, he and his brother were privately educated at home.

The Ross Expedition

In 1838 his father met James Clark ROSS who was organising an expedition to establish the exact location of the magnetic South Pole while concurrently engaging in other scientific research and exploration. Ross agreed to William Hooker's proposal that his son Joseph might be enlisted as a naturalist provided he first qualified as a doctor and entered the medical service of the Royal Navy. Joseph, already a student at Glasgow University, gained his MD in 1839 and Ross accepted him as an assistant surgeon on HMS Erebus. The ship's senior surgeon would undertake any zoological investigations and delegate botanical research to Hooker. A similar demarcation of duties prevailed in the sister ship HMS Terror. The official journal which Hooker maintained and his extensive correspondence with his family and friends are the primary source of information about a voyage which lasted four years.

The two ships sailed on 30 September 1839 via Tenerife, the Cape Verde Archipelago and St Helena for Cape Town where the first magnetic observatory was established. Wherever the ships stopped Hooker collected and recorded the local flora. Kerguelen's Land {Iles Keguelen} introduced him to sub-Antarctic vegetation, mainly mosses and lichens and some flowering plants. He botanised intensively during a three month stay in Van Diemen's Land {Tasmania} where another magnetic observatory (Rossbank) was erected. 'My collections I think improve as I go on, at least the collecting comes with greater facility to me,' he told his father on 9 November 1840. He was surprised to discover tree ferns as far south as the Lord Auckland Islands. In January 1841 the ships passed the farthest point south reached by Captain COOK in 1774. A party landed briefly on Possession Island off Victoria Land, an active volcano on Ross Island was named Mount Erebus, and the ships traced the formidable wall of towering ice ('The Great Ice Barrier' now known as the Ross Ice Shelf) for several hundred miles. Deteriorating weather and approaching winter forced a retreat to Tasmania. After a second visit to Sydney in New South Wales the expedition anchored in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand in August 1841. On his second survey of Antarctica Ross returned to the Great Ice Barrier, this time following a more easterly course, always apprehensive of the encircling pack ice. When his crews believed they had seen the last of the icebergs, one loomed up out of the darkness causing the ships to collide. After emergency repairs and 135 days at sea, Erebus and Terror sailed into Berkeley Sound in the Falkland Islands on 6 April 1842.

The Falkland Islands

Hooker's first impressions were unfavourable. Charles DARWIN before him had described the landscape having 'a desolate and wretched aspect' and Hooker thought that bleak and stormy Kerguelen's Land was 'a paradise to it. Desolation stares in our faces'. His official journal recorded that the 'land seen in the morning was low but hilly with many white quartz cliffs but little broken land except towards the hill tops'. In the late afternoon the ships anchored off Government House, a low whitewashed building on a hillside close to the water. Nearby was a settlement of about a dozen 'very miserable-looking' houses, no more than 'very poor, mud or stone huts'. He thought better of the two storey wooden dwelling belonging to JB WHITINGTON, the resident storekeeper. They were welcomed by the governor Lieutenant Richard MOODY of the Royal Engineers who had taken up his appointment that January with twelve sappers and miners and three of their wives. He hospitably offered Ross the loan of horses and dogs and made his 'excellent library' available to Hooker, who judged him:

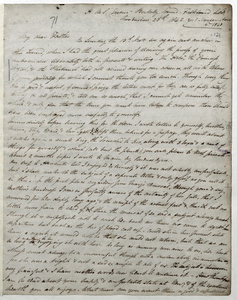

A very active and intelligent young man most anxious to improve the colony and gain every information respecting its products, so he has engaged me on the Botany and more especially on the grasses of the soil for he finds that his fodder grass will not make good hay; nor will the sedge do for thatching, or will either do for a lawn. As you may suppose I am very proud in being useful to him. I have found an excellent Triticum for thatching in the rocky coast and also some Poa and Agrostides for sheep & lawns which he will try to make useful. (Letter to Aunt Palgrave, 25 April 1842.)

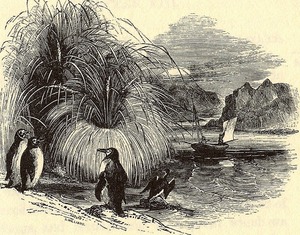

Hooker was not the first botanist to survey the Falklands. When Comte de BOUGAINVILLE brought the French settlers in 1764, his chaplain and amateur botanist, Antoine Joseph PERNETTY botanised in East Falkland. He is not known to have collected any specimens although he mentioned some by their colloquial names in his account of the voyage published in 1770. Ross erected a magnetic observatory in the old French fort built by Bougainville. The first collection was probably made by L Née, a botanist on Captain MALASPINA's expedition at Port Egmont in West Falkland in December 1789 and January 1794. In 1820 a frigate L'Uranie belonging to a French scientific expedition was wrecked on the Falklands. All that Hooker found of it were a few fragments of wood and 'some copper and a few iron water casks'. However its botanist, C Gaudichaud-Beaupré, succeeded in salvaging his collection of dried plants of which 128 species had been gathered in the Falklands. He presented a memoir entitled Flore des Iles Malouines to the French Academy of Sciences in 1825. The following year another flora with the same title appeared in the Memoires de la Société Linnéenne. Its author J. DUMONT D'URVILLE, Captain of the Coquille had anchored in the Falklands in November 1822. Just over a decade later Charles Darwin on HMS Beagle made a token collection of plants. A Mr Wright who had returned from 'a mercantile voyage to the Falkland Islands' presented Sir William Hooker in 1841 with a beautiful collection of plants. Sir William was intrigued by Wright's descriptions and drawings of tussock grass and densely tufted cushion plants compared by Wright to 'small haystacks'. He wrote to his son still serving on Erebus: 'How much I wished I could have reached you with letters at the Falkland Islands. I would like you to investigate the botany & zoology of those islands to the utmost of your power' (20 March 1842).

Despite the onset of winter with snow and heavy frost Hooker found more flowering plants than he had expected. He conjectured that the absence of tree cover was due to the low rounded hills with their broad shallow-bottomed valleys providing no protection from prevailing winds. He climbed Mounts Vernet and Lowe, crossed the sand hills between Ports William and Jackson (now Stanley Harbour), and reached the beaches at low tide. He notes the 'streams of stones' in the valley bottoms which every traveller since Pernetty had also observed. (Darwin wrote at length about them.)

He admired 'the pride of the Falklands' Oxalis enneaphylla (Scurvy Grass), covering the banks at Berkeley Sound 'with a mantle of snowy white' during the spring month of November. He saw this plant only in the Falklands, whereas Calceolaria fothergillii, (Lady's Slipper), Viola maculata, (Yellow Violet), and Hebe elleptica, (Native Boxwood), were also widespread in Tierra del Fuego off South America. A celery growing along the shoreline, Apium australe, (Wild Celery), was enjoyed as a vegetable by Ross's men. The natural spinach, a species of Atriplex, was another culinary favourite. The settlers and especially the gauchos used Myrtus mummularia, (Teaberry), as a substitute for tea.

The sands and peaty soils of the Falklands are colonised by many grass species. Tussock grass, (Poa flabellate), excited the attention of Governor Moody when he perceived its potential not only as fodder but also as an agricultural crop on the poor soils on the west coast of Ireland and on the Hebrides. He offered for renting or purchase 300 acre plots on small islands covered with this grass. He grew it himself in an experimental garden and infected Hooker with his enthusiasm. It was, Joseph Hooker told his father, 'the gold and glory of the Falklands and will yet I hope make the future of Orkney and the owners of the Irish peat-bogs.' The wild cattle and horses liked it so much, he told his sister, that they would eat dry tussock thatch from the roofs of houses in preference to other grasses. Vast tracts of the Falklands were covered with its gigantic hemispherical hillocks up to five or six feet high. Each clump supported about 200-300 blades of grass and the spaces between each community of clumps Hooker likened to a 'labyrinth'. Pernety and Gaudichaud had inevitably called attention to it, but Hooker was the first to describe it with botanical precision. It featured prominently in the report that Moody prepared for the Colonial Office recommending that it should be brought to the attention of botanists in the Linnean Society of London.

Equally striking in the landscape was the balsam-bog (Bolax gummifera), the 'misery balls' of the settlers. Two to three feet high and pale or yellowish green in colour, these balls reminded Sir William Hooker of 'gigantic pin-cushions' when he saw a sketch of fields full of them. Joseph Hooker also found tussock and balsam-bog in Tierra del Fuego, but never so luxuriant as those in the Falklands. Where there were no flowering plants to collect, Hooker concentrated on cryptogams - mosses, lichens and oceanic algae. 'Sea weeds abound prodigiously in the outer rocky coasts, nor did we elsewhere see such enormous masses of marine vegetation as were cast upon the beach of the east shore of the Falklands' (JC Ross: A Voyage...) Hooker was pleased to write to his father in May that:

every day adds something new to my collection, especially among the lower tribes...Altogether this place is better for botany than I had expected and but for lichens etc. it beats Kerguelen's Land [but] collecting here is no sinecure for the days are very short and the nights long.

Four months later he claimed triumphantly that he had found all but three or four of the plants listed by Gaudichaud and was confident that little else had escaped his meticulous searching.

Among the European plants deliberately or accidentally introduced to the Islands, Hooker recognised chickweed, shepherd's purse, dock and Poa annua. Dutch clover formed a rich pasture near Government House where sheep contentedly grazed. French settlers had brought livestock with them, rabbits, cattle and horses, which now thrived in vast numbers. Over the years they had scarred the landscape with tracks leading to their favourite feeding grounds in the tussock grass. The day after Erebus had arrived Hooker joined a hunting party to kill some cattle for fresh meat for the crew. Gauchos, one of whom was an Englishman, lassoed and slaughtered them. His journal describes the excitement of the chase and the kill:

...the dogs soon caught one cow by the nose and tongue whilst a third held him [sic] by the tail till a man came, hammering him and with two strokes of the knife plunged it into its throat, kicked the dogs off who commenced licking the blood and gave chase to the rest of the herd.

This brief extract conveys the flavour of Hooker's narrative skills. Ross's account of the voyage has a much longer account of a wild cattle hunt 'furnished to me by an officer who accompanied the party' without disclosing his name. Darwin who suspected that it had been written by Hooker could not understand why the contribution was anonymous. Hooker's informative correspondence and his Himalayan Journals (1854) confirm his literary ability and there can be little doubt that he was its author. Perhaps he modestly requested Ross not to reveal his identity.

In June 1843 the Colonial Office printed Moody's report and in 1842 the Journal of the Geographical Society published Sir William Hooker's enthusiastic letter on tussock grass. Sir William also extolled it at some length in his London Journal of Botany (1843) which he reprinted as Notes on the Botany of the Antarctic Voyage ... with observations on the tussock grass of the Falkland Islands (1843). He reported that 'Kew Gardens had been overwhelmed with applications from the proprietors of sandy and peaty soils throughout the British Dominions'. A Wardian case of living plants which included this coveted grass had been despatched from the Falklands but unfortunately none had survived the long sea voyage. The Gardener's Chronicle (4 March 1843) confirmed its hardiness on non-productive soils and the Royal Agricultural Society presented Moody with a gold medal for his efforts in promoting an awareness of tussock grass. Eventually Kew Gardens propagated it but its seeds frequently failed to germinate. When at last it was established in the Hebrides and Orkneys it grew too slowly to be considered a viable economic crop. Joseph Hooker suggested other Falklands plants that might be useful in agriculture and medicine, but nothing came of his recommendations. However he did compile the first comprehensive survey of the Islands' vegetation in Flora Antarctica (1844-7). He also contributed a succinct botanical résumé to the second volume of Ross's narrative of this epic voyage.

On 8 September the ships sailed to Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago off the southernmost extremity of South America. At Hermite Island the two crews saw their first trees since leaving New Zealand. Hooker harvested an abundance of plants in a region he rated 'the greatest botanical centre of the Antarctic Ocean'. They were stored on both ships together with about 800 deciduous and evergreen beeches for planting in the treeless Falklands. The cargo also included tree trunks for roofing the houses there. On 14 November this botanical bounty was unloaded at Berkeley Sound. Much later Hooker learnt that not a single plant from Hermite Island had withstood the climate, the neglect of the settlers or the voracious appetite of the goats. The ships were then overhauled in preparation for the third sortie to Antarctica. Provisioned with some calves, sheep and pigs with tussock grass for fodder to ensure a supply of fresh meat they left the Falklands on 17 December 1842. After enduring exceptionally thick fog, gales, blizzards, spray that froze to the riggings and decks, constantly alert to drifting icebergs, Ross reluctantly decided to end the expedition. The Erebus and Terror reached Folkestone on 4 September 1843.

Back in England

Hooker rejoined his family at Kew Gardens where his father was now director. The Admiralty retained him as an assistant surgeon with an additional allowance in order to write his account of the botany of the Antarctic voyage. The first two volumes entitled Flora Antarctica appeared in ten parts between 1844 and 1847. Hooker engaged specialists to enumerate the cryptogams and wrote at length about some of his more spectacular finds which included the tussock grass. This work established his reputation as a taxonomist and as a promising plant geographer, although he later confessed that the Flora Antarctica 'nearly broke my back'. Charles Darwin who congratulated him became an intimate friend, the two men frequently exchanging information and ideas with Hooker acting as a critical sounding board for Darwin's emerging theories on the variability of species.

The Himalayas

In 1847 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. The Admiralty sanctioned a trip to India on half pay, initially for two years to which another year was subsequently added. His father was able to enhance his pay by getting approval for his son to collect plants for Kew. He left England in November 1847 and explored eastern Nepal and Sikkim whose flora was little known. He surveyed and mapped the country as well as collecting plants. Roads and paths where they existed were poor; he was frustrated by suspicious villagers and briefly imprisoned by the Rajah's men. He sent both seeds and dried specimens of rhododendrons to his father who described some of the more decorative species in Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849-51). New species of primulas and Meconopsis dominated the alpines, which he introduced to British gardens. He was reminded of the Falklands streams of stones when he encountered similar phenomena in Sikkim. His Himalayan Journals (1854) is now a minor classic of travel literature. If Hooker had excluded its botanical content, Darwin declared that the book would still have been 'a very remarkable undertaking for its geology, meteorology, zoology and geography'. The same eclecticism distinguished his personal letters and official journal written during the Antarctic voyage: a curiosity about other cultures, a nodding acquaintance with zoology and more than an amateur's knowledge of birds. Although he had vowed never to embark again on a major flora, he joined forces with Thomas Thomas to compile one of India. Flora Indica (1855) never got beyond the first volume, but it laid the foundation for his Flora of British India (1872-97) in seven volumes.

On his return to England in 1852 he married Frances Harriet Henslow whose father was Professor of Botany at Cambridge. In 1855 he was appointed Deputy to his father at Kew Gardens, succeeding him as Director ten years later. In 1858 he and the geologist Charles Lyell arranged a meeting at the Linnean Society of London where papers by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace on evolution and natural selection were read. He vigorously defended Darwin's theory at the celebrated debate in Oxford in 1860. A brief visit to the eastern Mediterranean in the autumn of 1860, a collecting expedition to Morocco in 1871 and a leisurely tour in the USA in 1877 completed his overseas travels. Just before he left for America he was gazetted a Knight Commander of the Star of India for his services to India.

When he was in the Falklands he told the botanist George Bentham that the 'geography of plants is a favourite subject with me'. He had noted that two plant families that particularly interested Bentham - Labiatae and Leguminosae - were not represented by any species in the sub-Antarctic islands or in the Falklands or Tierra del Fuego. He was also surprised to encounter European species in the southern hemisphere. The similarity of Tierra del Fuego's flora to that of isolated islands thousands of miles to the east intrigued him. Could ocean currents and prevailing winds have dispersed these plants, or had there once been land links now submerged? His Flora Antarctica subscribed to the proposition that these Antarctic islands might be the summits of a former mountain chain and that their flora were the vestiges of the vegetation of this sunken land mass. In 1883 the Royal Geographical Society awarded him its Royal Medal for his 'long continued researches in botanical geography'. His wife died in November 1874 and in August 1876 he married Hyacinth Jardine, widow of Sir William Jardine, Bart. Hooker had seven children by his first wife and was to have two more by his second.

Last years

In 1885 he retired from his post as Director at Kew. With the completion of the multi-volumed Flora of British India in 1897, he was advanced to Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India and the Linnean Society struck a special gold medal in recognition of his services to botany over sixty years.

By then the doyen of polar exploration, he was consulted about preparations for a National Antarctic Expedition under the leadership of Robert Falcon Scott. He recommended the inclusion of an observation balloon to view the terrain beyond the high wall of the great ice barrier. His attention was again being focussed on that part of the world which had launched his career. 'I shall end my active life as I began it, in the interest of Antarctic discovery' he told a friend in 1897. On the eve of his second expedition to the South Pole in May 1910, Captain Scott invited Hooker to hoist the white ensign on his ship Terra Nova. Hooker's infirmities compelled him to decline an honour 'which would have been the crowning one of my long life could I have accepted it'.

Almost up to his death at his house in Sunningdale in Berkshire on 11 December 1911, he continued identifying dried specimens of the complex genus Impatiens. He was buried in the churchyard of St Anne's church on Kew Green next to his father with whom he had enjoyed a special rapport. Unlike his diplomatic and tactful father, he could be impulsive and brusque in manner and he seldom concealed his dislike of bureaucrats, qualities that were not always conducive to smooth administration at Kew. He was loyal to his friends who knew his personal integrity, admired his scholarship and who acknowledged with numerous honours and awards his many achievements. He is remembered on the Falkland Islands by Hooker's Point, a small headland east of Stanley and he was commemorated in a 1985 set of British Antarctic Territory stamps on naturalists.

External links

See: The Story of Joseph Hooker and Kew Gardens

See: Joseph and William Hooker’s Early Years (Vimeo video)

See: Flora of Fuegia and the Falklands

See: Letter from Hooker to his father written while he was in the Falkland Islands 5 April 1842

References

Joseph Hooker; Flora Antarctica: the botany of the Antarctic voyage. 3 vols, 1844 (general), 1853 (New Zealand), 1859 (Tasmania). Reeve, London; 1844–1859

Ray Desmond;Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker: Traveller and Plant Collector. Antique Collectors' Club; 1999

Comments

Revisions

June 2019 One illustration and one photograph added

August 2019 Two external links added

December 2019 Two additional photographs added; two references added; one additional external link added

January 2020 Three additional photographs added

March 2021 One additional image added; one external link added

July 2021 One additional photograph added