MOODY, RICHARD CLEMENT

1813 - 1887 from Barbados (also England)

governor, was born on 13 February 1813 at St Anne's Garrison in Barbados, the second son of Thomas Moody from Cumberland who had made his career in the Royal Engineers in the West Indies and his wife Martha Clement, the daughter of a wealthy Dutch estate owner.

Moody was educated privately in England and in 1827 entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and was later appointed head of the Academy. In 1829 he was attached to the Ordnance Survey, he was gazetted second lieutenant in 1830 also in the Royal Engineers and served with the Survey in Ireland in 1832. In 1833 he was posted to St Vincent in the West Indies where he suffered a severe attack of yellow fever, after which he went on convalescence to tour the United States with a Sir Charles Smith, a senior Engineer officer who had acted as governor for several of the West Indian islands.

He returned to Woolwich in 1838 as assistant professor of Fortifications, until - in his words - as 'merely a subaltern of Engineers, recommended by Lord Vivian, the late Master General of the Ordnance' he was chosen in July 1841 at the age of 28 to become lieutenant governor of the Falkland Islands.

Appointment to the Falklands

In fact there seems little doubt that his father, then serving as an adviser in the Colonial Office, obtained the appointment for Moody and ensured that he would be accompanied by a small but vital group of Royal Sappers and Miners. Certainly civil servants seemed dismayed by the size of Moody's party and therefore its probable expense. When Moody was selected no decision had been reached in London on the future of the small British settlement at Port Louis in the Falkland Islands. He was instructed to proceed to the Falkland Islands as lieutenant-governor for 'superintendence and making certain enquiries on the result of which steps will hereafter be taken for establishing a regular authority'.

The secretary of state Lord John Russell stressed the tentative nature of his appointment and informed him that his limited authority should be:

One of influence, persuasion and example, rather than direct authority; but in the exercise of moral rather than legal power, you must of course be guided by your own discretion, rather than by any precise instructions...

He was also told to consult a judicious naval officer to determine the most eligible port for the new colony. In choosing a ship for his expedition, Moody was to earn the enmity of the Whitington family and this feud was to embitter his entire term as governor. GT WHITINGTON a London merchant had adopted a proprietorial attitude to the new colony and believed that Moody should charter his ship to take the party to the Islands. But his tender was too high and Moody rejected his offer of a corrupt private deal so that relations were soured both with GT Whitington - who pilloried Moody in the Colonial Magazine (of November 1844) - and with his younger brother John Bull WHITINGTON who had emigrated to the Islands in 1840 and was the most substantial figure in the small society of Port Louis.

Arrival and First Impressions

Granted a budget of £2000, of which £600 was his own salary, Moody set sail with his party from Woolwich in the brig Hebe on 9 October 1841. They arrived in Port Louis on 16 January 1842 and Moody addressed the few residents, reassuring them that no great changes were envisaged for the colony, but warning that the paper dollars issued by Louis VERNET would not be honoured. One month after his arrival Moody sailed on a short cruise around East Falkland, touching once only on West Falkland. He was collecting impressions and opinions for his magnum opus - the General Report upon the Falkland Islands which he completed on 14 April and sent to London on 3 May. For a newcomer with only three months experience of the Islands, Moody's General Report is remarkably comprehensive, outlining the resources and potential of the Islands, finding both promising and recommending settlement. He drew attention to the likelihood that sheep farming 'would answer well upon a larger scale' and to the potential of tussock grass. The Report has a primitive innocence about it: the prospects were pleasing, everything seemed possible and Moody had yet to face the problems of inadequate immigration and investment and lukewarm support from the Colonial Office. The botanist Joseph Dalton HOOKER who arrived with the ROSS expedition on 6 April found Moody sympathetic 'Lt Moody seems a very active and intelligent young man, most anxious to improve the colony and gain every information respecting its products' he wrote home. Hooker encouraged Moody to promote tussock and indeed it created a considerable stir in England - the Royal Agricultural Society later awarded Moody their gold medal for encouraging its cultivation.

Site for the Chief Town: the birth of Stanley

Moody's instructions had raised the question of the site of the new settlement and mentioned the Admiralty's preference for Port William as a harbour over Berkeley Sound (where Port Louis was situated). The debate on the virtues of the two harbours lasted for eighteen months, and even the firm decision of the new secretary of state, Lord Stanley, which Moody received on 18 August 1843, did not end the discussion. Captain James Clark Ross the senior naval officer to visit the settlement in Moody's first year argued trenchantly in favour of Port William in August 1842 and his advocacy convinced the Governor. Although Moody faithfully reported Ross's views he does not seem to have believed that they would carry the day. Aided by his surveyor Murrell Robinson ROBINSON, he pressed on with an elaborate town plan for Port Louis (which he renamed Anson after Admiral Lord ANSON who had advocated the colonisation of the Falkland Islands) and allocated holdings of town, suburban and country land.

When he received Stanley's peremptory command to abandon Port Louis and build a new chief town, Moody naturally obeyed. But he shared the feelings of outrage of all the settlers and wrote a strong - even heated - despatch which drew attention to the colonists' 'disgust' at the change and the need to offer them new allotments in exchange for their investment at Port Louis. The first detachment of Sappers started work on the south shore of Jackson's Harbour in the winter of 1843 and the move of the administration to Stanley - as Moody requested the new seat of government be called - during 1844. The Governor himself finally moved to the new town on 15 July 1844. Moody produced no grand design for the layout of Stanley. He had considered four sites before settling on the south shore and he mentioned the long sea front and the ease of unloading cargo along it as a positive advantage.

Moody himself soon came round to Stanley as chief town and reported optimistically to Whitehall on the improvement to the ground produced by drainage and grazing and the general contentment of the settlers. He reacted with understandable irritation to a despatch from London recording Commander SULIVAN's scepticism and replied firmly that the decision was now made and accepted.

Finance

The colony was to be funded and administered on the same pattern as more established British colonies. Estimates were prepared and accounts submitted. It was soon clear that Moody had not been fully briefed on his responsibilities as 'Accountant' for the colony. His first accounts were improperly submitted and a slow process of distance learning set in hand which was to last for his entire government: just before he left in 1848 he was replying to the auditors' criticisms of his accounts for 1843/4.

Soon after his arrival Moody was guilty of two financial heresies: he levied a tax (on alcohol - to deter drunkenness) without the approval of any legislative body and he issued promissory notes to make up for the lack of specie in the colony. Both measures were pragmatic responses to serious problems, but this did not soften London's reproof and the issue of personal notes was criticised in Parliament (by Sir William Molesworth).

Government was the prime economic actor in the colony but the years 1841-8 saw the growth of JM DEAN's business as he rose from a humble agent to JB Whitington to become an auctioneer and storekeeper. In 1847 Samuel LAFONE's cattle hunting enterprise was established at Hope Place and 70 gauchos imported from Uruguay to procure a constant supply of fresh meat for the settlers and passing ships. But Lafone's agent Richard WILLIAMS had difficulty in ensuring a constant supply of fresh beef and relations with Moody (as later with Governor RENNIE) quickly became very strained.

Land and Settlement

Moody had recommended in his General Report that immigrants should be brought in from Scotland. But government was not prepared to subsidise emigration to the Falklands and the optimistic tone of the General Report was followed by increasing depression as the flow of immigrants and particularly of 'capitalists', failed to materialise. Government was not prepared to foster settlement and it was difficult for settlers already in the Colony to obtain land from government. The move from Port Louis to Stanley, and the delay in agreeing that land in the old settlement could be swapped for land in the new were further discouragement.

As the negotiations between the Lafone family and the Colonial Office progressed, Moody urged that the sums received from Lafone should be used to establish smaller farms in the Islands, but Whitehall - having spent considerable sums in establishing the Colony, wished to pocket most of Lafone's payments. It was in any case difficult to allot land when the Camp had not been surveyed and when any method of demarcating plots was bound to be laborious. However on 2 July 1847, Moody introduced a temporary system whereby tracts of land could be leased and this aroused some interest among settlers and, perhaps surprisingly, was not criticised by Whitehall.

Administration

Moody's initial position as lieutenant-governor was reinforced in June 1843 when the Colonial Office promoted him to governor and commander-in-chief and instructed him to establish a normal colonial administration with Legislative and Executive Councils.

In a despatch of 19 July 1842, Moody had already requested assistance in the shape of a court of judicature, a doctor and a clergyman to care for the physical and moral health of the colonists. The Colonial Office responded reasonably promptly and Dr Henry James HAMBLIN arrived in November 1843 while the Reverend John Leith MOODY (the governor's brother) landed in October 1845.

Administratively more significant was the appearance of the stipendiary magistrate William Henry MOORE in March 1845 and of the governor's private secretary JH SLAUGHTER in November 1843. The colonial surgeon Hamblin had brought with him his wife and her mother and brother JR LONGDEN - the last was to prove an able clerk and was to move on to a distinguished career in the Colonial Service.

ExCo and LegCo first met in October and November 1845 respectively. They were drawn from the small group of 'respectable' officers about the Governor: Moore, Hamblin and the Rev Moody. The settler Whitington who should - socially - have been eligible was ruled out by his feud with Moody, but Richard Williams - Lafone's agent - was later to join Council. The Secretary of State was not happy with a clergyman on either Council and Moody agreed to remove his brother - only to find that the latter took bitter offence.

It would be pleasant to report that reinforcement made the governor's life easier. But the new officials introduced new points of friction. Moody had already dismissed his private secretary and chief surveyor Murrell Robinson Robinson after a furious row in March 1845. He soon found that the stipendiary magistrate Moore was a self-important shyster with a weakness for drink. And the colonial chaplain, his brother James Leith Moody, turned out to be querulous and eccentric. Slaughter - the new private secretary - was 'of a morbid disposition' and soon asked to go home.

The last three years of Moody's governorship were marked by long and bitter exchanges of correspondence with those who should have been his supporters and allies. Moody tried without success to persuade London to remove Moore. With James Leith Moody relations were poor, but less openly hostile. While Moore and the Rev Moody were the governor's chief adversaries in the paper battles which fill the archives, there were others with whom he exchanged bitter reproaches. Commander Sulivan, the Captain of HM survey vessel Philomel, who should have been a natural ally, crossed Moody in April 1845 when his officers provided hospitality to Murrell Robinson Robinson during the latter's dispute with Moody. The storekeeper Edmonds engaged in a correspondence of extraordinary impertinence with the Governor in 1847-8: so much so that Moody was less outraged than concerned at his subordinate's inability to perceive his place in the hierarchy.

Moody as Governor

So many of the problems of Moody's term in the Islands seem directly attributable to his personality. Querulous he undoubtedly was - partly perhaps a family failing, but also because he felt insecure. As a mere lieutenant when he was dispatched to the Islands, he was diffident and morbidly sensitive to slights - real or imagined - from senior visiting naval officers.

Unfortunately almost no private letters from Moody survive from his term in the Islands. In personal terms the most revealing despatch is his long account of his relations with Murrell Robinson Robinson in which Moody explains that he had chosen to remain aloof from the colonists. He seems to have shunned personal confrontations: his dispute with John Bull Whitington in 1844 concludes with a refusal to grant a personal interview because it was 'unbecoming my station to take any further notice of this individual'.

The history of the latter half of Moody's governorship can almost be divided into chapters covering his successive disputes with his subordinates: Robinson in 1845; WH Moore in 1846 and 1847; the Rev JL Moody in 1847 and 1848; Edmonds the clerk in 1847; and Richard Williams, Lafone's agent, in 1847 and 1848. These can be charted in wearying detail through a succession of letters and notes, sometimes revealing major differences of principle but often simply petty. A stronger character would have cut these tangles with personal interviews, but Moody preferred to engage in salvos of correspondence. In fairness, his subordinates were often difficult and some slightly deranged.

Moody served almost seven years away from home in a severe environment and in a tiny community. For much of the time he was in temporary quarters or boarding with Dr Hamblin and his family. Although he designed Government House in Stanley, only the east wing was completed during his tour. During his first two years he showed energy and curiosity in promoting his new domain. He proposed exporting dried meat and fish to the mainland and compressing peat to power steamships and he produced a detailed proposal for establishing a penal colony on the Islands. His salary was increased from £600 a year to £800 in 1845. But his enthusiasm was gradually eroded by feuds with his subordinates, disputes with settlers and disagreements with visiting naval officers. When his father was posted from the Colonial Office to Guernsey and when Lord Grey assumed the mantle of Secretary of State in June 1846, Moody found the Colonial Office less understanding, colder and reproachful.

Moody's Achievement

As the first governor, Moody deserves credit for establishing a regular administration in the Falkland Islands. The archives, which effectively date from his arrival, show that within the limits of his resources order was imposed on an unruly settlement, land was surveyed, letters answered, and some law imposed on the fractious ships' captains, traders, whalers and wreckers who made up the sea-faring community. The two Councils - Executive and Legislative - were established, as were Courts of Law - however unsatisfactory the magistrate. The new capital of Stanley was laid out and a nucleus of dwellings, storehouses, jetties and corrals built on a barren shore. A school, a church, a cemetery, a gaol, a militia, a police force were established. Lafone's project was launched, however uncertainly, and was to develop into the largest enterprise in the Islands - the Falkland Islands Company.

Less impressive was the slow progress made in settling the new colony. Far from the race of thrifty 'capitalists' Moody looked for, the settlers who arrived tended to be sailors who had jumped ship or been shipwrecked, or British refugees from the upheavals around the River Plate. Moody was scathing about:

...our community ... chiefly composed of men of the lowest class, formerly seamen in whale ships & sealers, foreigners and Spanish gauchos...the only persons opposed to such wretched material for the formation of a colony are the 5 or 6 gentlemen and the detachment of Royal Sappers and Miners.

The 1840s were a time of distress in Britain and famine in Ireland and Moody can scarcely be reproached for sharing the prejudices and fears of a gentleman of his time. As an officer and as governor he was concerned for the welfare of those in his charge, but he could not help wishing that they were more thrifty, more reliable and more sober.

If Moody's greatest failing was his inability to lead his senior government officers it may be doubted whether - even with a more loyal and effective team - he could have achieved much more. Until the Colonial Office was prepared to set out clear guidelines for settlers it would be difficult to persuade immigrants to invest in land. And the colony was too new and too little known to attract the maritime traffic which was to provide a living for Stanley in the l850s and l860s. It took the Californian gold rush of 1849 to bring the haven offered by the Islands to the notice of the shipping trade.

Back in England

Moody left Stanley on HM transport Nautilus in July 1848 reaching England in February 1849; he was entitled to a year's leave. He was promoted first captain in August and attached to the Colonial Office where he advised on the arrangements for sending the military pensioners to Stanley. After a brief posting in Plymouth he was appointed Commanding Royal Engineers in Newcastle. It was here that in July 1852 he met and married Mary Susanna, the daughter of Joseph Hawks, a JP and deputy lieutenant. They were to have eleven children. Moody was posted to Malta in 1854, but obliged to return through ill health. Promoted lieutenant-colonel, he was appointed Commander, Royal Engineers, Scotland. He enjoyed the intellectual company of the Scots capital and pursued his interest in architecture, drawing up plans for the restoration of Edinburgh Castle, which he was asked to present to Queen Victoria, but which were never implemented.

British Columbia

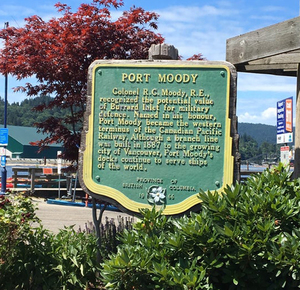

In 1858 Moody was promoted to brevet colonel and appointed lieutenant-governor and chief commissioner for lands and works in the colony of British Columbia. Accompanied by his wife and four children he left England in October and arrived in Victoria on Christmas Day. The colony was under pressure from the United States and a gold rush was bringing large numbers of prospectors across the border. Moody had a detachment of 172 Royal Engineers under his command to defend the colony and provide survey and road building support. Shortly after his arrival Moody faced down a notorious outlaw Ned McGowan and fractious gold miners without loss of life. He then selected a site for the new capital of the colony and named it New Westminster. Much of his time and that of the detachment of sappers was spent in clearing the site and opening roads around it. Unfortunately Moody failed to get on with the governor of the colony, James Douglas, who knew his parish well and was not overly impressed by either Moody or the sappers. In 1863 Moody and the detachment were recalled and he returned with his family (now of seven children) and those sappers who did not wish to settle in British Columbia. Moody left his library behind to become the public library of New Westminster. It is reported that he also left his native American housekeeper with two children.

Last Years

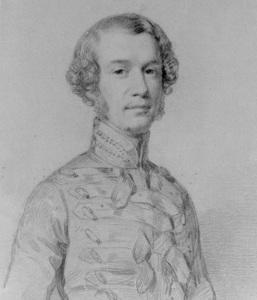

Moody was put in command at Chatham in 1864 and retired from the army in 1866 with the rank of major-general. He had decided that he could no longer impose the rigours of a military career on his large family. He lived quietly in Lyme Regis, Dorset and died of a stroke on 31 May 1887 while visiting Bournemouth with his daughter. He left over £24,000, a considerable sum for the time. Moody was a member of various learned and professional societies - the Royal Agricultural, the Royal Geographical and the Institute of Civil Engineers. Just before his death he was elected an honorary associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Several photographs of Moody (and one of his wife) were taken in Canada and a family sketch of him as a young officer is above. He is remembered by Moody Brook near Stanley and by several place names near Vancouver - Port Moody and Moody's Inlet. He featured in the Anniversary of Stanley series of Falkland Islands stamps released in 1994.

External links

References

National Archives, Kew. Files in series CO78/4 to -/19.

JCNA, Stanley. Letter books from the years 1842-8. Moody’s key ‘General Report’ dated 14 April 1842 is reprinted in the Falkland Islands Journal 1969.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Article by John Sweetman. Oxford University Press, 2004. (Also Website)

Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Article by Margaret A Ormsby. University of Toronto, 1982. (Also Website)

Institute of Chartered Engineers, London.

Comments

Revisions

May 2019 Corrections to text

June 2019 Five additional photographs added

September 2019 References added; external link added