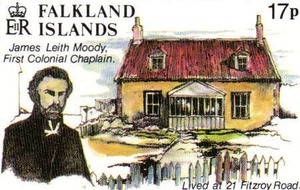

MOODY, JAMES LEITH

1816 - 1896 from Barbados (also England)

colonial chaplain was born in 'Baladon BI' (not located, but probably Barbados) in 1816, a younger son of Col Thomas Moody RE and Martha Moody, née Clement. His Christian names reflect his father's admiration for the then commander in the West Indies, Sir James Leith. He entered St Mary's Hall, Oxford, in 1835 to study for the Church and graduated with a BA in 1840 (he later obtained an MA in 1863). He was ordained deacon in 1840 and priest in 1841, both by the Bishop of Lincoln, serving as curate in Radnage, near Oxford. Shortly thereafter he became a naval chaplain.

His father Colonel Moody's influence at the Colonial Office had secured the post of lieutenant-governor of the Falkland Islands for an elder son, Richard Clement MOODY, in 1841 at the tender age of twenty-eight. And six months after his arrival in the islands, the new lieutenant-governor appealed to London for a colonial surgeon and - so that religion could 'exercise its influence in maintaining good order' - a colonial chaplain. Whether the Moody family had already stitched up the post of chaplain we cannot know, but it was more than three years after his brother wrote to London asking for a chaplain that James Leith Moody arrived in Stanley, having spent the voyage from Río sleeping upon bolts of canvas with five other travellers. He had already spent four years at sea in 1845 in HM frigate Thalia.

The new chaplain's rather eccentric character is soon reflected in the government archives. Early in 1846 he reproved the magistrate WH MOORE for leaving the bodies of two drowned sailors exposed to the elements. In March 1846 he sought the governor's help in preventing the daughter of a settler, McIntosh, from going off to live with a gaucho by the Government Corral at Sparrow Cove - this he said could have a demoralising tendency. In May he appealed for an increase in salary because of the high cost of food, fuel, washing and servants and because he had had to import his furniture from Río. He had already asked London for home leave, within four months of his arrival at Stanley.

The governor appointed his brother a Justice of the Peace and shortly afterward nominated both James Leith Moody and the magistrate, WH Moore, to the new Legislative and Executive Councils which London had instructed him to form. It was not a happy experiment for either Moody, because the Colonial Office disliked the presence of a minister of religion on the councils, and moreover would not agree that he should be a JP. The chaplain was obliged by his brother to resign these posts and wrote to London in protest. It must have been some consolation that he was granted an increase in salary and permission to take leave, although he did not choose to take this leave. One would expect two brothers, exiled in a small community more than three months sailing from England to be on terms of close friendship. It was not to be. James Leith had no hesitation in protesting to the governor about the failings - real or imagined - of his administration. In January 1847 he wrote to the colonial secretary protesting at the failure of the government to answer letters or keep office hours. He protested to the governor when the Communion table was used as a writing table for the jury, because the same building served as church and courthouse. In November 1847 he denounced the state of the Stanley graveyard and commented acidly: 'I trust Your Excellency, as soon as you have completed your arrangements for your private convenience around Government House, will give your attention to this subject'.

Equally bitter was a letter to the governor about a bill which Dr HAMBLIN had sent the chaplain's servant. James Leith wrote - with heavy sarcasm - that he would have preferred to leave the question until the next governor (George RENNIE) had arrived, given that the doctor's wife had been the governor's housekeeper, that Hamblin's brother-in-law (James LONGDEN) was the Governor's secretary and that the doctor himself was aide-de-camp. But, taking up a theme which was to become commonplace in the next few years, 'as Colonial Chaplain and therefore the natural guardian of the poor' he asked for an opinion. The governor curtly replied that this was a personal matter. Dr Hamblin wrote that the chaplain had displayed extreme ill will, not to say spite.

During his first few years in the colony, the chaplain had been establishing the Falkland Islands' first school, with only limited support from London. The school opened on 1 January 1846 and 12 children attended. Nine months later eight of these were still attending, but James Leith Moody regretted that the parents of seven other children would not allow them to attend the school, 'from an absurd idea that they would lose caste by allowing their children to attend the same school as those of sappers and working settlers.' He was not happy with the teacher, a youth of 19, and hoped that a respectable married woman would come out from England to teach the girls the use of the needle.

In January 1847 a new teacher was appointed but William Barry Brown proved less than satisfactory. Although the chaplain defended him, the settlers soon decided that he was effeminate and called him 'Miss Brown the schoolmistress'. When the Government storekeeper called him 'Sally Brown', the chaplain protested and, in the storekeeper's words, 'shook his forefinger in my face very angrily and said - I'll take you in hands on one of these days and surprise you.' However the school master and the chaplain must have fallen out, because on 5 April 1849 Brown wrote to the new governor to inform him that he was resigning as 'the children have been influenced to leave the school by the Revd. JL Moody...'

In July 1848 the chaplain's brother handed over as governor to George Rennie, an older and more experienced man who had been a Member of Parliament. In April 1849 the bibulous and corrupt magistrate Moore left to be followed by a slightly more judicious figure, Algernon MONTAGU. The colony was developing: in October 1849 the military pensioners arrived, thirty of them roughly equally divided between Protestants - mostly Anglicans - and Irish Catholics. The Protestant pensioners were obliged to attend church after their weekly muster on Sunday mornings and it was their view of his sermons which led to a major row between the chaplain and the governor, and a 'trial' of James Leith Moody before successive sessions of LegCo in March and April 1852.

It is clear that in these years, James Leith Moody's behaviour had become steadily more eccentric, not to say deranged. He had alienated almost all the 'respectable' colonists, and government officials no longer attended his services. His preaching was becoming more paranoid, condemning the drunkenness which was a feature of the young colony but also referring to tyrannical governments in terms which alarmed the commander of the pensioners, Captain Reid, and the senior NCOs, Sergeant-Major FELTON and Sergeant Smith, and caused gossip among all the ex-servicemen.

On 16 March 1852 Governor Rennie summoned the ExCo, which amounted to the new magistrate Montagu and the colonial surgeon, Dr Hamblin. In ten sessions stretching over a month the Council examined the pensioners, listened to the chaplain's defence and went on to take the views of several of the leading colonists, culminating in a bitter account by John Bull WHITINGTON of Moody's cruel failure to ride to Port Louis to bury his infant son. The sessions are interesting not just for what they reveal of the increasingly contorted mind of Moody, but also for the insights they give us into the daily life of Stanley in the 1850s.

The Council questioned a good number of pensioners. One was too drunk to reply and several were too canny to become caught up in a dispute between their social superiors. But Captain Reid and Sergeant Smith both recalled that Moody had preached against tyrannical governors and had once implied that the governor himself was guilty of breaking the Sabbath by being absent from Stanley one Sunday. Reid felt uneasy that he compelled the Protestant pensioners to attend Church services where this sort of sermon was preached. So the governor drafted a long letter to Moody, taking up his preaching, but broadening the case against the chaplain with a number of charges:

The governor added that Moody had an important mission as a chaplain in the Falkland Islands. There were no sectarian animosities - 'the Catholics even accepting your offices at christenings and burials' and the opportunities for healing dissensions and promoting harmony were great. Moody replied with a long letter asserting his loyalty to the Queen and those in authority under her and picking up the specific accusations.

An entire volume of papers at the PRO is devoted to the case of the Rev Moody. One official minuted: 'I should take him to be a homely and not too cultivated man - he is the brother of the former Governor Capt. Moody, and seems to have been ten years a ship's chaplain, but honestly anxious to do his duty'. As in the case of Mr Moore, 'Governor RENNIE showed very little scruple in getting rid of an officer he (perhaps with good reason) disliked by bringing very paltry charges against him'. The Colonial Office did not sympathise with the governor, did not approve of his proceedings against the chaplain and indeed admired the Rev Moody's fearless admonition against the prevalent vices of the colony.

In the event, Moody left the colony on leave in 1854 and never returned. He became a chaplain to the forces in 1854 and in 1859 he was assistant chaplain to the forces, Aldershot. Crockford's Clerical Directory states that 'he served at Gibraltar, Malta, China, Crimea, etc.' In Crockford's for 1865 his address was given as Walmer, Kent. He was placed on the retired list in 1876, and became Rector of Virginstow, Launceston, Cornwall, until 1879. He was Vicar of St John the Baptist, Clay Hill, Enfield, from 1879 to 1885, when he retired to Dulwich. From the 1881 Census, we know that he married Mary, who was born around 1833 in Hertfordshire and had three children: William (b c1865), Alicia (b c1869) and Reginald (b c1878).

He died in Dulwich in 1896, leaving effects worth over £4,000. His wife Mary died on 28 July 1930 in her ninety ninth year.

He is remembered by a stamp in the Foundation of Stanley series of 1994, although his portrait by James Peck was necessarily indistinct, as no-one knew what he actually looked like.

Comments

Revisions

July 2019 Minor correction to text

February 2020 Three additional photographs added