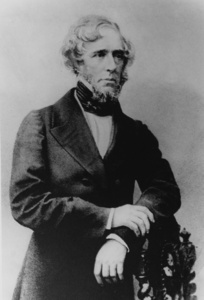

RENNIE, GEORGE

1802 - 1860 from Scotland

governor and sculptor, was born in Phantassie, East Lothian, son of George Rennie, agriculturalist and nephew of John Rennie the well known engineer. He studied sculpture in Rome and on his return to London in 1828 he exhibited at the Royal Academy and with the Society of British Artists. He worked on narrative subjects (The Gleaner, The Minstrel) and portrait busts of his contemporaries in a classical style. In the 1830s he devoted his attention to improving the state of the arts in England and in 1836 he suggested the formation of a parliamentary committee which led to the establishment of the School of Design at Somerset House. He also worked to obtain public access to museums, suggested bringing Cleopatra's needle to London and in 1839 submitted an (unsuccessful) design for the national memorial to Admiral Nelson in Trafalgar Square.

In July 1841 he was elected as Liberal MP for Ipswich, but held the seat for less than a year as his election was declared void in May 1842. He stood again for Ipswich at the general election of 1847, but was induced to withdraw by the government fixer, Tufnell, to make way for another candidate. Rennie pressed the government to find him a colonial governorship in exchange for his help and eventually Lord Stanley, the secretary of state for the colonies, appointed him governor of the Falkland Islands on 15 December 1847.

Governor

Rennie, accompanied by his wife Jane and his three sons, George, William Hepburn and Richard Temple arrived in Stanley on 27 June 1848 in the naval transport Nautilus after a voyage of four months. His predecessor Richard MOODY left for home on 15 July. Rennie proved a competent administrator and the Colonial Office noted an improvement in the colony's accounts. He set about establishing a garden and bought a cow for milk and butter, a General Improvement Society was formed and after its first show in April 1849 Rennie was able to report that 'every useful kind of green crop or garden produce can be raised'. Indeed on 30 July 1849, the governor was able to cease the monthly distribution of rations, which had been a feature of the early days of the colony.

The Growing Economy

In October 1849 the military PENSIONERS arrived with their families and were allocated land and housing. The population of the colony increased substantially and the 1851 census showed a total of 383. A boost to the economy was the discovery of gold in California in 1849 and in Australia in 1850, leading to a surge of traffic along the sea lanes round Cape Horn. The number of vessels calling at Stanley rose from 12 (totalling 9,200 tons) in 1849 to 55 (totalling 24,000 tons) in 1855. The possibilities for the sale of meat, fresh vegetables and water increased in proportion. The demand for carpenters, shipwrights and other craftsmen was acute and their wages reached levels which scandalised ships captains and merchants. The prefabricated iron lighthouse was constructed on Cape Pembroke in 1854 and lit for the first time before Rennie returned home.

The main player in the Islands' economy also took shape during Rennie's time. The brothers Samuel LAFONE and Alexander LAFONE had signed an agreement with government to slaughter the wild cattle on the broad acres assigned to them. The Lafones never visited the Islands, but their manager, Richard Almond WILLIAMS, was an abrasive character little inhibited by laws or agreements. He imported large numbers of gauchos from Montevideo without respecting the Aliens Act and discharged them at the end of the season without a fare home. The purchase of Lafone interests by the London-based Falkland Islands Company in 1851 improved matters. Samuel Lafone appointed John Pownall DALE from Montevideo as manager and he arrived in July 1852: his relations with Rennie were amicable, but in 1854 he was replaced by Thomas HAVERS from London, a less co-operative figure.

The search for guano produced an unfortunate incident. Early in 1852, Rennie sailed in the barque Levenside for New Island to collect samples to be sent to London for analysis (together with samples of fine sand for possible use in glass making). On her return, the Levenside struck a submerged rock near Cape Pembroke and quickly sank. There were no casualties, but the ExCo minute book, which the colonial secretary had taken along to write up, was lost. Analysis of both the guano and the sand concluded that it would not be economic to develop them.

In 1852 work was started on the Exchange Building, a long single story construction with a handsome Italianate clock tower which was probably designed by Rennie himself. The building, completed in 1854, contained a market area and one end was used as the Anglican church. It dominated views of Stanley until the second peat slip in 1886 destroyed it.

Personalities

Rennie had chronic problems with his unbalanced colonial chaplain, James Leith MOODY and his shyster magistrate William Henry MOORE. He received less than wholehearted support from the Colonial Office. An official noted that in both cases: 'Governor Rennie showed very little scruple in getting rid of an officer he (perhaps with good reason) disliked by bringing very paltry charges against him'. In the end Moody took leave and did not return, while Moore revealed his true colours during leave in London and was forbidden to return. The next magistrate, Algernon MONTAGU, was also a tricky character whom Rennie suspected of advising his opponents. Rennie was ably supported by the colonial secretary James LONGDEN who provided continuity and a safe pair of hands. His son William Hepburn Rennie took on occasional tasks in government and acted as a magistrate during the case of the American whalers. It was the first rung in a career which would lead him to service in Hong Kong and finally to become lieutenant-governor of St Vincent in 1872.

The Germantown Incident

A serious international incident erupted in 1854. Rennie had reported the appointment of WH SMYLEY as US commercial agent in Stanley in 1851. In February 1854 Rennie asked for naval support to arrest American whalers who had been shooting cattle for provisions, and Commander BOYS was sent down from Río de Janeiro in the brig HMS Express. But Smyley too had sent for support and the powerful frigate USS Germantown (Captain LYNCH) arrived in Stanley harbour on 2 March to find HMS Express escorting the delinquent American ships into the bay. An exchange of correspondence with the hot-tempered Lynch followed but Rennie was able to quote a note from the US Secretary of State, Marcy, who had warned American ships' masters and other citizens that if they committed spoliations in the Falklands, they would incur penalties. Lynch intimidated the courthouse with his ship's guns and while the whalers were found guilty, their fines were light.

The incident soured Rennie's relations with Smyley: the accredited agent of the United States, wrote the governor, was abetting the lawless acts of his countrymen. For his part the American denounced Rennie who 'has shown his inveterate hatred to me and all my countrymen'. Lynch reappeared in August 1854 to enquire into the arrest of another American captain, Bernsee of the barque Courier. But Bernsee had been released and Lynch left without further incident.

The Crimean War (1845-6) caused some concern: the nightmare was a Russian privateer attacking the undefended colony. A volunteer force was raised.

Return

On 4 June 1855 Rennie wrote a strong plea to return home; public works in and around Stanley had been completed. The Colonial Office were sympathetic; they believed Rennie 'has shown energy and ability during the seven tedious years that he has administered the government of these remote islands'. In considering a new governor, one official noted: 'It is I believe admitted that Mr Rennie's administration and development of this small populace is deserving of commendation'. The government grant had fallen from £5,700 a year to £2,807.

Rennie left the Islands on the Java, bound for Falmouth, on 5 November 1855. He was able to report: 'the Colony is abundantly supplied with all the necessaries and many of the luxuries of life...Labour is in good demand ... Pauperism is entirely unknown'. The population had risen to around 600 persons.

Rennie seems to have disappeared from public life after his return, though in 1858 he did apply without success for a governor's post in Moreton Bay {Brisbane} Australia. He died at home in York Terrace, Regent's Park, London on 22 March 1860.

Rennie was fortunate because two significant sources of income became available to the colony during his term as governor: the Falkland Islands Company and the ship supply and repair trade. But he provided safe and consistent government for his seven and a half years and saw the colony safely through the Germantown crisis in 1854. On his departure many of the classic features of the colony had taken shape. The FIC was ensconced as the principal proprietor and substantial storekeeper, often in a state of tension with government. Other farmers had bought land on East (though not yet West) Falkland. The Patagonian Missionary Society had established their base on Keppel Island. Stanley Harbour was busy.

Rennie, certainly the most artistic of Falklands governors, handled a young and uncouth community with some skill.

External links

See: The Falkland Islands Journal 1996

See: Hansard 1803-2005 George Rennie's contributions to Parliament

References

Major R N Spafford; 'George Rennie, Governor of the Falkland Islands 1848-1855'; Falkland Islands Journal; 1996

Comments

Barb

2018-09-29 02:26:28 UTC

Wonderful article, thank you!

Revisions

July 2019 Two photographs added; external link and reference added

September 2019 Additional reference added

December 2019 Two additional photographs added

October 2020 One additional illustration added