SMYLEY, WILLIAM HORTON (various spellings)

1792 - 1868 from United States

American sea captain and consul, was born in Providence, Rhode Island. James W Smyley, a ship's master who visited the Falklands in the 1840s may have been a brother. WH Smyley's letters, with their eccentric spelling and grammar (which have been generally corrected in this essay), suggest that he had little formal schooling. He must first have come to the south Atlantic in the crew of a sealing or whaling ship during the 1820s - in 1850 he wrote that he had spent 22 years of his life 'mostly from South Shetlands to the River La Plata'.

Smyley and Vernet

In December 1829 the Bellville from Massachusetts arrived in the Islands. Louis VERNET chartered the ship for cargo work, but she was wrecked on Tierra del Fuego, and the crew made their way back to the Falklands in a small shallop constructed from the wreck's timbers, arriving on 30 May. A group of men from the Bellville, with Smyley among them, were wandering around the Falklands, presumably sealing, and Vernet arrested them briefly before taking them into his service. (The US minister in Buenos Aires, Francis Baylies, mentioned Smyley among those arrested when he protested to the Argentines.) Smyley and others signed an agreement to work for Vernet building a shallop on Eagle Island. This vessel, the Aguila, or Eagle, was captured by Captain DUNCAN of the USS Lexington when he approached Port Louis in December 1831.

In November 1831, just before the destruction of Port Louis by the Lexington, Vernet issued Smyley with a document commissioning him as branch pilot for Port Louis, Port William, Choiseul Bay and 'for other ports, bays and waters under my jurisdiction'. A document which makes no reference to the Argentine government which had appointed Vernet commandante of Port Louis, but one which confirms that Smyley was already an experienced navigator in Falklands waters.

Sealing and Antarctica

Smyley's first voyage as ship's master was in the schooner Sailor's Return which left Newport, RI, on 3 July 1836 and made good time southwards by keeping close into the corner of Brazil (rather than sailing across to the coast of Africa and then back). Smyley hunted seals in the Falkland Islands and the South Shetlands. A second voyage in 1837 ended with the Sailor's Return wrecked on a reef off the coast of Brazil. In April 1839 he sailed south again as master and part owner of the schooner Benjamin de Wolf and reached Port Egmont in only 41 days. After sealing in the Islands and again on the coast of Patagonia, Smyley returned with 1,375 fur seal skins and 150 hair seal skins - not an enormous haul. In 1840-41 he made a repeat voyage in the Benjamin de Wolf. On both voyages, the British naval officers in charge at Port Louis reported Smyley's presence with concern.

His next voyage in the 125 ton schooner Ohio proved to have some scientific significance. Smyley left Newport on 14 July 1841, sailed down to Staten Island {Isla de los Estados} and then across to the South Shetlands. On Deception Island in February 1842, Smyley recovered the maximum and minimum temperature thermometers left by HMS Chanticleer (Captain Henry Foster) in 1829. When Smyley picked up the maximum thermometer, the indicator slipped making the reading unreliable. But the minimum one produced a reading of -5 degrees Fahrenheit, and until 1895 this was the lowest temperature recorded in Antarctica.

As Smyley left Deception, the Island erupted: 'the South Side of the Isle was all on fire, there being 13 volcanoes and many other places where you might pick up Sinders [sic], the water was boiling hot in many places in the harbour'. His description of the event was borne out by accounts of an eruption in 1969, when twenty vents erupted along a great fissure five miles long.

On leaving Deception, it appears that Smyley sailed south-west, possibly as far as 66 degrees south sailing through the Pendleton Strait to reach Cape Horn. His sealing cannot have prospered as he picked up a return cargo of coffee in Brazil, reaching New York in July 1842.

In September 1842, Smyley set off once more in the Ohio, accompanied by the Sarah Ann, a 60 ton schooner. He was part owner of both vessels. He sealed off the Río Negro in Patagonia and reported that despite keeping careful watch in the long summer days he had seen no sign of La Agle Shoal. But the Ohio was wrecked on the coast of Río Negro on 27 March 1843, 'with bare time to save my crew and only succeeded in doing so by taking part of them on the spars of the vessel nine miles,' wrote Smyley later. Later that year Smyley shipped supplies from Río to the garrison in the Falklands on the Sarah Ann.

A bold adventurous man...

The establishment of British rule in 1833 and the arrival of a lieutenant-governor in 1842, should have restricted his sealing around the Islands. But unless a naval vessel was present in Falklands waters, Smyley was free to act as he pleased. His reputation certainly alarmed Governor MOODY, who wrote to the British admiral at Río de Janeiro in October 1845, that Smyley was 'a bold adventurous man of high courage and little enough of principle'. Moody noted that Capt Grey in HMS Cleopatra had tried to capture Smyley, who had robbed the Isla de Lobos near Montevideo. It was possible Smyley would try to capture the colonial chest at Stanley.

The classic description of Smyley's methods comes in a letter to the Secretary of State, WE Gladstone, of 10 July 1846 from the magistrate WH MOORE (who was embroiled in a commercial dispute with Smyley): he alleged that Smyley had intimidated the governor; that he had defied Royal Navy captains; that he had sealed illegally on the Isla de Lobos; and that he had donned British uniform to hoodwink an American sealer into handing over his catch. But Governor Moody had already had a private talk with Smyley in June 1846. The latter had:

Deposited with me...a great number of papers and singular documents giving me a curious insight into his past and present proceedings in these seas. These documents ...remove much of the bad impression I confess I entertained towards this individual and strengthened my opinion of his activity, skill, courage and enterprise.

This did not prevent Moody from writing sharply to Smyley on 8 June, requesting him to close the gunports and unload the two guns on his ship Catherine as they were causing 'uneasiness to many'.

Smyley had continued shipping supplies from Río Negro on the Coast to the infant colony, using first his schooner Sarah Ann (60 tons), then the Catherine (74 tons) and finally the barque Christiana (252 tons), which he had bought in Stanley.

Marriage

On 29 March 1839, Smyley married Evelina J Chafee, daughter of Otis Chafee in New York. She died on 23 June 1847 and is buried in Island Cemetery, Newport. His second wife, Catherine Clapp, accompanied Smyley when he settled in Stanley. They had two daughters there: Evelina Jane (b1852) and Catherine Rebecca (b1858). A son, William Horton Smyley, was baptised in Stanley in 1859, but presumably born in the United States during the family's absence from the Falklands between 1854 and 1856. Smyley rented Seal Island from government in 1857 and at his death owned two half acre sites in Stanley.

Consul and Commercial Agent

In February 1851, Governor RENNIE reported that Smyley entered his office wearing diplomatic uniform to announce that he was the Commercial Agent of the US Government. He had indeed been appointed by the US Secretary of State Daniel Webster on 12 September 1850 during his visit to the States. He was also appointed US Consul at Río Negro in Argentine Patagonia, but noted that the dictator of Argentina, General ROSAS, did not wish to accept consuls outside the capital, Buenos Aires. Smyley was always conscious that his post was an expense to his government: 'it is all out go and no in come'. He received a salary of $500 a quarter which he seldom drew as American Bills of Exchange were rarely accepted in Stanley.

Smyley reported shipping movements, shipwrecks and import figures to Washington, while his deputies, first JB WHITINGTON and then JM DEAN, both leading figures in the colony, corrected his spelling and brushed up his prose style. Fortunately they did not blunt his vigorous style, usually directed at the colonial government or, as he described it in 1854: 'the despotic power which here exists'. As for Governor Rennie: 'that despotic governor ... seemed to throw every obstacle in my way', while his son who served as a magistrate 'has not common sense and not as much brain as a cabbage'.

The Germantown Incident

Three years after his appointment, early in 1854, Smyley was to confront Governor Rennie in a series of incidents resulting from the governor's determination to make American ships' captains subject to the colony's laws. In February HMS Express was sent to arrest two American whalers for killing wild cattle in West Falklands. Smyley, who had been warned by the governor on 23 January that he intended to take the American ships at New Island to task, had summoned the USS Germantown, a powerful frigate with a fiery captain, NF LYNCH, from Montevideo. Shortly after Lynch's arrival, the whalers Hudson and Washington were shepherded into Stanley harbour by HMS Express. Smyley took Lynch to call on the governor and a heated exchange followed. Lynch loaded his guns and trained them on the courtroom; the American whaling captains escaped with light fines.

Smyley was closely involved with a second dispute in 1854. An American, Captain Bernsee, had lost his ship the Courier wrecked near Bull Point in Lafonia on 1 April. To pay his crew, he sold the wreck and contents at auction and was then arrested for breach of the auctioneer's ordinance. Smyley had been present at the illegal sale (though he did not report this to Washington) and had advised Bernsee that he might have problems. Bernsee was released after two and a half months mild confinement (Smyley dined with him many nights - champagne was sent in) and sailed for Montevideo on 17 August. On 23 August, Captain Lynch paid a second visit to Stanley to enquire into the Bernsee case. He exchanged ill-tempered letters with the governor, who declined to see him; again threatened to bombard the settlement; and finding Bernsee already released, left after three days.

Smyley had left with the crew of the Courier for Montevideo in June. His relations with Rennie were at breaking point. The governor 'has shown his inveterate hatred to me and all my countrymen' wrote Smyley. Since the Germantown had left in March, Smyley felt he had been 'like a target to be shot at'. He resented American sailors being fined for killing animals which their predecessors, not the British government, had placed on islands. He challenged British authority outside the town of Stanley and assured the magistrate, MONTAGU, that the American flag would soon wave over West Falkland. For his part, Rennie believed that the accredited agent of the United States was abetting the lawless acts of his countrymen.

From Montevideo, Smyley left for home later in 1854, having decided that it was not worth returning to the Islands while Rennie was governor. In October 1856 he returned to Stanley: 'my reception was very flattering and everyone in the colony gave me such a hearty welcome'. The new governor, Thomas MOORE, was a naval captain, as was his successor MACKENZIE. It was understandable that they got on better with Smyley than Rennie had. But increasingly, Smyley's major service to his country and to the whole south Atlantic region became the rescue of shipwrecked sailors from the shores of the Falklands, Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego.

The Work of Rescue

In October 1851, as the captain who knew these shores best, Smyley was approached by Samuel LAFONE in Montevideo to find and assist the Patagonian Missionary Society (PMS) party led by Captain Allen GARDINER, which had been landed by the Beagle Channel in 1850. In foul weather Smyley sailed around Staten Island, first discovering the shipwrecked crew of a Danish ship, the Alladen. Then, in Spaniard's Harbour on the north shore of the Beagle Channel, he found the possessions and bodies of three of the seven missionaries. But before he could investigate further, he was forced to put to sea by a sudden change in the wind and had to sail north to leave the Danes on the coast of Patagonia and to re-provision at Montevideo. Returning south he recruited fresh crew at the Falklands and set off again for Tierra del Fuego. But on the second trip the weather was no better and he could find no trace of the party.

Smyley undertook a succession of cruises along the coasts of South America and the Falkland Islands. In 1857 he rescued the crew of the American ship Great Republic and helped to bring her safely into Stanley Harbour (where he complained prices were extortionate). In 1858 he rescued the sole survivor of the Belgian ship Leopold from the Jason Islands; he was to receive a telescope from the King of the Belgians in thanks. In 1859, when the Dolphin was shipwrecked on the Coast of Patagonia, he observed that if the crew should fall into Indian hands:

I may have much trouble to ransom them... as for the character of these Indians perhaps I know them better than any man living - and the better you know them the more you dread them. I have been their guest at one time and their prisoner at another.

His most well known exploit was the rescue of the sole survivor of the PMS party on board the Allen Gardiner. In March 1860 Smyley sailed to Tierra del Fuego in search of the Allen Gardiner. He found the ship at anchor, deserted and later he discovered the cook, Alfred Coles, who alone had survived the attack of the Fuegians. It had been a hectic mission - 'I did not even take off my clothes from the day I left until I returned' - but it won him great acclaim. The Royal Humane Society awarded him a medal; the Patagonian Missionary Society presented him with a Bible.

Reporting his 1851-2 rescue attempts to Washington, Smyley complained of the expense, but added:

...as there is no other person here who owns or keeps a vessel, it falls very hard on me but yet how can I refuse. It is not alone for our countrymen but for all nations and often my will is better than my means & in the next place we have so little communication with any place. It may be considered we are almost out of the world.

Smyley's relations with the manager of the FIC, Thomas HAVERS, a commercial rival, were unhappy. In 1857 Havers reported to his head office in London that Smyley had been stealing cattle in Lafonia and on Saunders Island. Smyley had carried off one prospective witness, but was eventually brought to trial and convicted of killing one bullock and fined £2. Havers continued:

This man has an expensive vessel here kept for no ostensible use, he comes and goes as he pleases and no-one cares to ask him how he earns his living. He and I are on quite good terms notwithstanding the trial and yet I know him to be little better than a pirate, being well acquainted with some extensive robberies he has committed ...The people here are all more or less afraid of Smyley and it is not easy to induce anyone to speak out ...

Last Years: 'one of our best consuls.'

In March 1861 he told the State Department that he wished to place his children in a school in America ('we are in a den of corruption' in Stanley) and warned that 'my health has been very poor of late'. His doctors had told him to leave the Islands and get some rest. But that same month the British admiral visiting Stanley greeted him warmly and was delighted when Smyley offered to pilot HMS Ardent to New Island. He was granted six months leave the following year but by then the American Civil War had broken out, with the real risk of conflict with Britain. He could not leave his post: 'I keep my vessel well manned and with three months provision aboard ready to slip from her moorings and proceed off Cape Horn to notify all our vessels'. He sent his wife and children home and noted that the government 'treat me with every respect, but at the same time they watch me like a cat would a mouse'. In February 1864 he reached Montevideo, but returned to Stanley to help an American ship laden with arms for San Francisco, which was leaking. Finally he sailed north again, leaving Montevideo for the States in June 1864 in his ship the Kate Sargent. At the end of 1865 he wrote that he had been received 'with great civility in the Treasury and the State Department and on my arrival in New York I received a most flattering reception from the New York underwriters'. He asked for a small steam launch which he could carry south on his ship for use in rescue work, but nothing came of this.

In April 1866 he was back in Stanley, and in August he proposed to sail to Río Negro as the town was likely to come under attack from Indians and was poorly defended. There is no sign that he went. On 2 March 1868, JM Dean reported to Washington that Smyley had died of cholera in Montevideo on 13 February. The FIC manager FE COBB noted:

The Guerri è re has brought news of the death of Captain Smyley of cholera in Montevideo, just as he was about to return to the Islands. Much regret has been expressed here at this event and all flags, government ones included, have been flying half mast high as a token of respect. Captain Smyley was for many years a strong and inveterate enemy of the company and Mr Lane, but to me personally he had always shown a friendly feeling and more than one act of kindness and civility on his part have caused me to join in the general regret for his loss.

A US admiral, Davis, came south to arrange Smyley's affairs and A BAILEY and JM Dean were his executors. He owned two houses in Stanley and two schooners. His wife had remained at his home in Flushing, NY, since early in the Civil War.

In 1863 a State Department official had noted on one of his despatches: 'he is one of our best consuls, though as you will see he has not had a college education. He keeps a schooner employed in looking for shipwrecked seamen in the Straits...'

Conclusion

Smyley is one of the most remarkable characters of the early days of the colony and indeed in the history of Patagonia and Antarctica. Apart from his despatches to Washington and his official correspondence with Falklands governors, little that he wrote has survived - but then he was a man of action, not words. He lives in the impression he made on others, as a bold and skilful mariner, who moved from youthful escapades to mature philanthropy and eventually near-respectability. He deserves to be better known, both in the countries of the south Atlantic and in his native land. He is remembered by Smylie's Channel in West Falkland and Smylie's Creek in East Falkland

Editor's note:

I am grateful to Dr Claudio Antonini for pointing out that a Smyley Island exists in Antarctica at approximately 72°55’south and 78° west. Details may be found at the Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica,

https://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/gaz/scar/display_name.cfm?gaz_id=111241

References

Claudio Antonini; Piedra Buena, Smyley and the Bowery Theatre in New York

Comments

Revisions

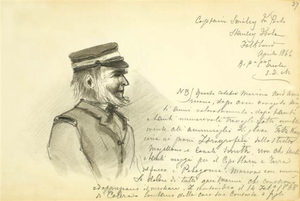

May 2019. Edoardo de Martino sketch added

February 2020 Two additional photographs added

January 2021 One additional image added; one reference added

March 2022 Editorial comment added