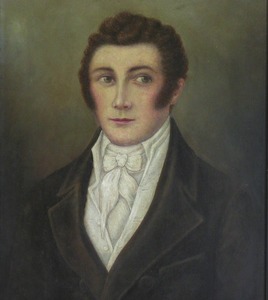

VERNET, LOUIS ÉLIE

1791 - 1871 from Germany (also Argentina)

entrepreneur and colonist, was born in Hamburg, Germany on 6 May 1791, son of Jacques Vernet and his second wife, Marie, née Simon; both were of French protestant (Huguenot) origin. Vernet spoke German and French as mother tongues, later learning English and Spanish. He called himself Ludwig, Louis, Lewis or Luis according to the language he was using. His family sent Vernet to Philadelphia in 1805 to join the trading house of Buck and Krumbhaar where he stayed with Lewis Krumbhaar who became a father figure. Vernet undertook several voyages to Brazil, Portugal and Hamburg and in 1817 founded a trading house in Buenos Aires with Conrado Rücker, also from Hamburg. On 17 August 1819, he married Doña Maria Saez a beautiful and cultured 19 year-old from the Banda Oriental {Uruguay}. From this union there were to be six children: Luis Emilio, Luisa, Sofia, 'Malvina' who was born in the Falklands, and whose real name was Matilde, Gustavo and Federico.

The Falklands Connection

On 1 July 1821 Vernet created a separate company and also took up slaughtering wild cattle. He also acquired an estancia just south of the Río Salado where he raised cattle. Here one of his brothers, Federico, and one of his brothers in law, Captain Antonio Saez, were killed by the native Indians. In 1819, he had lent money to one Jorge PACHECO, who was in turn owed money by the Buenos Aires government. Pacheco was connected by marriage to Bernardo BONAVÍA, a former Spanish commandant at Puerto Soledad (Port Louis). From him Pacheco and Vernet learnt of the wild cattle on East Falkland, and in 1823, they approached the government for the right to slaughter them. This was granted on 28 August 1823 and the two put an expedition together, in collaboration with a British immigrant, Robert SCHOFIELD. Shortly before the expedition sailed, Pacheco and Vernet hired a retired officer Pablo AREGUATI as expedition officer and local leader and on 18 December 1823, they petitioned the government to grant him the title of unpaid 'commander' - and to supply cannon. The land grant was made that same day - on condition of a proper survey. But Areguati was not given any rank - or any cannon.

This first expedition was a failure. One ship, Rafaela, left in December 1823 and was reported lost. The second, Fenwick, reached Port Louis on 2 February 1824 but found conditions very difficult. A third ship, Antelope, brought Schofield and Vernet's brother Emilio, but after a month Schofield, who had mismanaged everything and turned to drink, left again for the mainland causing the expedition to collapse. In July and August the expedition's employees were paid off in Buenos Aires. The total loss was nearly 30,000 pesos.

Recovering the loss - the 1826 Expedition

The only way of recovering this lost investment was to try again. In 1826, Vernet did so; this time handling things himself. New articles of association were signed on 25 November 1825. Vernet also made out a bogus contract ceding his grant to two British men. Vernet submitted this and Pacheco's 1823 grant document to the British vice-consul Richard Poussett for countersigning on 3 January 1826. This may have been simply notarial, but it is possibly the first indication of Vernet's fear of attack, and search for British protection. He purchased the British ship, Alert, and the new expedition was fitted out. It sailed on 12 January 1826. Vernet had some 200 horses left over from his cattle slaughtering activities near Río Negro. But it was 13 May, before he could get the best of these on board and not until 9 June that he landed on the Falklands. Vernet had had to land far from Port Louis just to save the starving horses and it took a difficult five day journey to reach Port Louis, on 15 June. A few days later they found 22 horses abandoned after the 1824 expedition in fine health and with these some cattle were immediately caught. Fresh beef lifted everyone's spirits - particularly the gauchos'.

The 1828 Concession

Over the next 14 months, Vernet chartered or bought a series of vessels to bring supplies, horses and people to his tiny settlement. Towards the end of 1827, he bought out all the remaining shareholders in his 1826 association. From then on he was alone. In 1828, Vernet approached the government in Buenos Aires in person with a colonisation proposal. He had despaired of ever repaying the money invested in his enterprise just from cattle. Instead he wanted to exploit the fishery and particularly sealing. Government aid was not possible, because of war with Brazil, but it offered to grant him East Falkland, if he would set up a colony himself which government could encourage with privileges. This led to the grant of 5 January 1828.

In addition to East Falkland, excepting the thirty square leagues previously granted to Pacheco, Vernet had petitioned for Statenland (Isla de los Estados, by Cape Horn), the right of fishery throughout the Falklands archipelago, and along the entire coast of the Republic, and freedom from taxes for 30 years. It was a breathtaking request - nearly all of it in places way beyond the real limits of Argentine authority at the time. Nevertheless, Vernet was granted all of Statenland (from where he could get wood) and what he wanted in East Falkland, except the land ceded to Pacheco (which Vernet later bought) and ten square leagues by San Carlos Water, which the government reserved to itself. He got the right of fishery along the mainland coast south of the Río Negro, and freedom from taxes for only 20 years. A condition of the grant was that Vernet had to form a colony within three years. This put him under constant pressure to get things done quickly.

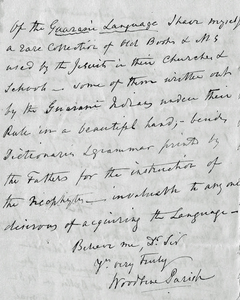

But Vernet must have known about the British claim by then. So he submitted his land grant to the British Consulate, where Vice-Consul Charles Griffiths counter-signed it on 30 January 1828. Whether Vernet saw the British minister, Woodbine PARISH, then is uncertain but Vernet certainly met Parish in 1829. Newspaper reports in March had revealed that a presidio, (a penal settlement and frontier garrison), was to be set up in the Falklands - almost certainly in the ten square leagues reserved by the government in Vernet's 1828 land grant. This alerted the British embassy to the fact that Argentina had official designs on the Falklands - it would not just be Vernet slaughtering cattle. Parish asked to see Vernet and, on 25 April 1829, he reported their conversation to the foreign secretary, Lord Aberdeen. Parish described Vernet as:

a very intelligent man who has passed three winters there, and is now returning with several colonists. To be located according to his agreement with the [Buenos Aires] Government...He would, I believe, be very happy if His Majesty's Government would take his settlement under their protection: - He sails for the Falklands with his family in about a month, and intends to pass he says some years there in promoting the objects of this colony.

Vernet also provided Parish with a copy of his grants, and a description of the people at his settlement, which Parish sent to Aberdeen as well. There were ten white inhabitants, natives of Buenos Aires, ten seafaring men, mostly English and Americans, Vernet's brother and brother-in-law, and 18 Negroes indentured for ten years and 12 Negro girls - 52 people in all. On the basis of these dispatches, the British Foreign Office instructed Parish to protest at this infringement of British sovereignty - this was before it knew about the formal Argentine claim to the Falklands which was to be announced on 10 June 1829.

The Comandancia and British Protests

Vernet had always wanted an armed ship with which to protect the seal fishery. In 1829 he approached the Argentine government of Juan Lavalle. It had seized power quite illegally in December 1828. But the Buenos Aires governor, General Martin Rodriguez, still managed to create the Falklands a comandancia - on 10 June 1829. That same day Vernet was made comandante politico y militar (CPM - military and civil commander) of the Falklands, although his appointment was never officially gazetted - and so was not strictly legal. Either way, Woodbine Parish reported everything to the Foreign Office on 26 June 1829. Vernet continued with his pro-British stance; even inviting Parish personally to invest in the settlement at Port Louis.

On 17 September 1829, Aberdeen by then also aware of the decree creating the Comandancia, again instructed Parish to protest. Parish finally handed Britain's formal protest to the Argentine government on 19 November 1829. Receipt of Britain's protest was acknowledged on 25 November 1829, but no reply was ever made. Argentina was in chaos, and there were probably more pressing things to do.

While Britain had been preparing and delivering its protest, Vernet returned to the Islands in the American brig Betsey, Captain Oliver Keating, with his own and five other families, German and British, 23 settlers in all. They arrived at Port Louis on 14 July 1829. The Betsey also landed 50 muskets, gunpowder, and six eight-pound cannons - but not a single soldier. It then sailed on to Isla de los Estados, to establish a sawmill there to supply the settlement with timber. Vernet's wife soon settled in. With her were her three eldest children, Emilio, Luisa, both still very young, and Sofia, still a toddler, plus their British governess, Miss Robinson. Matilde Vernet, better known as Malvina Vernet, was born in the Falklands - on 5 February 1830. With families there, the settlement assumed an air of permanence. It was now not just a temporary operation to end when the wild cattle were exterminated. Domestication was now the plan, so the cattle could be slaughtered and sold as demand required.

But Vernet was also trying to sell off land. On 29 October he sold ten square miles of land to a British captain, William LANGDON, who had arrived in his ship the Thomas Laurie. On his arrival in Britain, Langdon wrote to the British Government informing them of his land purchase and quoting Vernet as having no objection to British occupation so long as private property were not interfered with.

A British passenger with Langdon paints a glowing picture of the Vernet household with its good library of Spanish, German and English books, and music and dancing in the evening: 'Donna Vernet, a Spanish lady, favoured us with some excellent singing which sounded a little strange at the Falkland Isles where we had expected to find only a few fishermen.' The diaries of Vernet's wife and brother Emilio confirm this - although with all the problems of a tiny pioneer society in dangerous times.

The Sealing Problem - and Arrest of the American Ships

Vernet was soon joined by Matthew BRISBANE, whom he made director of the seal fishery. Vernet says in his memoirs that while the settlers working the cattle did well, those going sealing faired badly - because of the 'depredations' of foreigners. He had warned several off; but Vernet was playing a dangerous game. He did not want fishing to stop. He wanted sealers to pay licence fees. The Americans were not going to co-operate - they had fished in the Southern Ocean for more than 60 years. But Vernet needed more than money - he also wanted their ships. In his 'circular' to foreign captains he warned that their ships would be forfeit if they infringed the regulations.

In mid 1831, Vernet arrested three American sealing vessels, the Harriet, Captain Davison, followed by the Breakwater and the Superior. The crew of the Breakwater overpowered their guards and escaped back to the United States where the account of their capture was published in October 1831, causing widespread concern. President Jackson referred to it in his State of the Union Address of 6 December 1831, and promised to reinforce the American squadron in the South Atlantic to protect American interests. In the meantime, Vernet made a bizarre deal with Captains Congar of the Superior and Davison of the Harriet, dated 8 September. This allowed one ship, the Superior, to leave under new articles to Vernet, to go sealing on the Pacific side of Cape Horn, while the Harriet went for trial in Buenos Aires. The fate of the Superior was to be bound by the judgement on the Harriet. The profits would go to Vernet, if the Harriet were condemned, but to the vessel's original owner if they were acquitted. Vernet was mixing his supposed public role as CPM with his personal business interests as director of the colony in a very dangerous manner. He anticipated that the vessels and their contents would be declared forfeit and that he would be the beneficiary. Vernet himself took the Harriet to Buenos Aires for trial, leaving the Falklands on 7 November 1831.

The USS Lexington and after

The Harriet reached Buenos Aires on 20 November 1831 - and Captain Davison went straight to the US consul George SLACUM to accuse Vernet of piracy. Slacum protested to the Argentine Foreign Ministry at Vernet's seizure of the three ships and at Argentine pretensions in the Falklands. Receiving no satisfactory reply from the Buenos Aires authorities, Slacum consulted Captain Silas DUNCAN of the sloop-of-war Lexington and on 9 December, the Lexington sailed for the Falklands, with a vengeful Davison on board.

Slacum believed Vernet's colony threatened not just American sealing interests but might become 'another Cuba ...and our commerce round Cape Horn exposed to robbery and destruction by adventurers and vagabonds from all quarters of the globe'. Britain was also worried about the situation and Parish reported everything to the Foreign Office on 14 December 1831, enclosing a list of ships which had called at the Falklands, 'also a paper on the climate and production of the Falklands which Mr. Vernet has drawn up at my request'.

The Lexington arrived off Port Louis on 31 December 1831 and spent three weeks there, during which time DUNCAN took various steps to reduce the ability of Vernet's colony to harm US interests - he spiked the cannons, broke the muskets and burnt the powder. Mathew BRISBANE and six of Vernet's gauchos were arrested on a charge of piracy, and Vernet's Negro slaves and European settlers were induced to leave by warnings circulated by DUNCAN and Captain Davison that the settlement would be threatened again by US vessels. As a result, as well as the prisoners, Duncan took about 40 people away from the islands aboard the Lexington. Although most of them left as a result of these warnings, some had already been keen to leave. About 20-24 people remained at Port Louis: about fourteen gauchos, two black women, one child, and five Charrúa Indians. There is no evidence that Duncan's men did any significant damage to the houses. Accounts saying that the settlement was sacked or "razed" are untrue. The view of the United States Government and American sealers was that no sovereignty existed in the islands, and Duncan made a declaration to that effect. Accounts vary as to the precise wording of this. Statements later in the Argentine press by witnesses reported that he declared that the Islands were "the common property of all nations".

After this blow to his colony, Vernet and Argentina entered into a long legal battle with the Americans over the Lexington's actions. This opened when a new American chargé d'affaires, Francis Baylies, arrived in Buenos Aires in June 1832. He rejected Argentine pretensions to the Falklands on the grounds that they were British, and so justified the actions of the Lexington. In the course of this exchange, Vernet produced a seriously erroneous report for Argentine Foreign Minister, Vicente de Maza, that has misled historians ever since. In this Vernet claimed that Pablo Areguati had been made a governor, which was untrue, and that David Jewett (who Vernet wrongly referred to as Daniel Jewitt) had found fifty ships in the Falklands when he arrived in 1820 and had told them to stop fishing (for seals) and leave. Perhaps Vernet just confused his own activities with Jewett's. But perhaps, in such a difficult situation, he sought to justify his own actions by pretending that he was only continuing what others had done earlier. Whatever the reason, that is the origin of these myths.

The American diplomatic mission finally despaired and left Buenos Aires in September 1832 and the Argentines prepared to re-occupy Vernet's settlement, probably as an immediate snub to the Americans. But Vernet himself refused to return. He was effectively bankrupt, and stayed on in Buenos Aires trying to get the Argentine government to press the United States to compensate him for his losses. So the Argentine Government appointed a new commandant and sent twenty-six soldiers with him. This commandant, a Frenchman named Etienne MESTIVIER, reached Port Louis on October 6 1832, in the Argentine ship Sarandi. Just weeks later, on 30 November, he was murdered by his own men in a mutiny.

The British Return and the Port Louis Murders

The British chargé d'affaires in Buenos Aires had protested to the Argentine government yet again on 28 September 1832, reminding them of Britain's claim, and objecting to the appointment of Mestivier. Then, in January 1833, Captain ONSLOW (HMS Clio) landed at Port Louis and reasserted British sovereignty over the Islands. He told the tiny 26 man Argentine garrison, which had arrived with Mestivier just three months earlier, to leave, together with the ship that brought them. But Onslow urged the handful of genuine residents to stay - and most of them did. He appointed Vernet's Irish storekeeper William DICKSON as guardian of the British flag, and then left again himself.

Vernet sent Brisbane and three others back to the Falklands in March 1833. But Brisbane, Jean SIMON (his foreman), Dickson and two others were all murdered in the Port Louis massacre of August 1833 by some of the remaining gauchos and Indians. The reason was a dispute over payment for the construction of a corral, and Brisbane's continued use of Vernet's own paper pesos to pay the gauchos, which they so disliked. This was really the end of Vernet's operation. He could not go back himself without losing Argentine support in his claim against the Americans. Later that year, the British appointed Lieut Henry SMITH as naval officer in charge at Port Louis and Smith, and his son later kept Vernet's cattle business going. This lasted until Lieut LOWCAY took over in 1838. It is from then that Vernet dated the final loss of his business and property in the Falklands.

The years after the British re-occupation were difficult for Vernet who was effectively bankrupt. He stayed in Buenos Aires trying to use the government there to get compensation for his losses at Port Louis. But such was the chaos in Argentina that no envoy left for the United States until 1839. There Vernet's case got little sympathy. He made several approaches to the British Government. In July 1834, writing via Woodbine Parish, he offered his services to the British Government, and asked for British support to re-establish his cattle business and for Britain to either pay for the damage to Port Louis, so his claim on the United States could be forgotten, or support his claim on the United States. Britain was unwilling to do either.

Parish supported Vernet as the best qualified person to develop the Islands and Vernet reminded Parish of their dealings before the British returned in 1833:

I rely much on the foundation of the opinion you gave me several times ... That my individual rights and grants would be confirmed by H.B.M in case of taking possession of those islands. I trust herein upon the generosity of your Government.

But the British Government was not interested.

In 1835, Vernet asked Britain for permission to return to the Islands and for £4,000, or even £2,000, with which to re-establish his cattle business, but without success. In 1836, Vernet proposed a deal with a Uruguayan General, Antonio Lavalleja, to re-finance his cattle business in the Falklands. The British minister in Buenos Aires disliked this idea and Vernet quickly abandoned it. Later still, in 1838, Vernet sent a formal petition to the British Government to confirm his land grants, and to allow him to continue with his cattle business. It was all turned down, and Vernet was just given permission to go to the Falklands to take away his moveable property.

The Worm Patent - Vernet in Europe

In the 1840s Vernet developed a preservative for hides, a major Argentine export, often spoiled by worm, polilla. Vernet was granted Argentine and Uruguayan patents for this. He made the equivalent of ten thousand pounds by marketing it. Financed by this money, Vernet sailed for Britain to press his case for compensation. On 7May 1852, he presented his claim totalling £14,296 (about £28,000 with interest) to the British government. The wheels of the British government ground slowly, and Vernet's 1852 petition was sent out to the Falklands for the governor's comments. Only in 1856 did Britain make its first compensation offer. It would not, of course, recognise his claim to land, which depended on his grant from the Buenos Aires government. The cattle had been wild, and Vernet clearly had no real title to them either. His buildings were largely left by the Spanish, and were in very poor condition by 1833. But the British government did accept Vernet's claim for his horses, at only £20 per horse. The British offer was a total of £2,400, of which it proposed to withhold £850 against possible claims on Vernet from the Falklands - some of his paper currency was still there. Vernet rejected this in December 1856 and refused a later more forthcoming deal.

While in Europe, Vernet also visited his birthplace Hamburg looking for help in his claim against Britain. It was no use. The city government there replied that his parents had considered themselves French and had not taken Hamburg citizenship. Vernet also went to Paris, claiming that he had never taken out Argentine citizenship, to seek French help, again without success. In both Hamburg and France, he also promoted another South American land settlement scheme, in Bolivia, on land owned by Colonel Manuel-Louis de Oliden. It all fell through because of doubts over access, frontier disputes and the financial crisis caused by the Crimean War.

On 1 February 1858, an embittered Vernet finally accepted the British offer of £2,400, of which only £550 would be withheld. But the question of whether Vernet would waive other claims dragged matters on until May. Vernet had just received news of the death of his wife in Buenos Aires and was deeply depressed. He considered that his waiver of further claims was being extorted from him. After accepting the £1,850, and waiving further claims, he tried to reopen the matter in June 1858. But Britain held him to his waiver and immediately rejected this.

Last Years

Vernet returned to Buenos Aires ruined financially. But he had not given up and turned his attention to his claim on the United States where his daughter Malvina, had married an American named Greenleaf Cilley. They began lobbying the Argentine minister in Washington but without success.

The Falklands had effectively been forgotten by the Argentine government after the 1849 Convention of Settlement with Britain. In 1868, while Vernet was still alive, the Argentine government granted Isla de Los Estados, part of Vernet's 1828 grant, to the Argentine explorer and sailor, Luis PIEDRA BUENA. On 9 October 1869, Vernet signed a contract with his eldest son Don Emilio Luis Vernet, for him to pursue Vernet's various claims: against the USA (for the Lexington raid), against Britain (for unsatisfactory compensation), and against Silas E Burrows, owner of the Superior for non-fulfilment of the contract signed by Captains Davison and Congar back in 1831.

Vernet's contract with Emilio mentions him 'being old and requiring tranquillity' and he died on 17 January 1871 at his house in San Isidro, just outside Buenos Aires. He was buried in the Recoletta cemetery, Buenos Aires, beside his beloved wife, to be later joined by his sons Carlos and Emilio and his daughter Malvina.

But the Vernets persisted with their family claims. In the 1870s, hoping to increase their inheritance, Emilio and Carlos successfully petitioned the Argentine government for compensation for the loss of Isla de Los Estados. They also tried to get compensation for the loss of East Falkland - although this was not forthcoming. Then in 1884, they did get support from the Argentine government of President Julio Argentino ROCA who reopened both the Lexington claim on the United States and the Falklands claim on Britain. The Argentine claim on the US was rejected by President Cleveland in 1885.

The grudge against Britain led to the 'Affair of the Map' in 1884 when the Falklands were included in a map of Argentina being prepared by the Argentine Geographical Institute. This led to British protests and marked the first step in the resurrection of the Argentine claim to the islands.

Louis Vernet impressed almost everyone who met him as a man of intelligence, charm and organising ability. But he could be highly authoritarian too. Although he is celebrated on Argentine stamps as a patriot, specialist Argentine historians consider him a traitor, because of his dealings with Britain, both before and after the British return to the Falklands. He was not always truthful in what he said, and his falsehoods have sometimes misled historians. Some Argentine historians even consider him to have been something of a cheat, and he certainly was mainly motivated by the prospect of making his fortune. This was what led him to seize American ships, which he hoped would become his property. This was folly. He must have known that the US maintained a squadron in the South Atlantic, and were likely to defend interests which dated back decades before his own arrival on the scene. His settlement, which had just begun to prosper, was destroyed as a result. This involved the fledgling Argentina in a dispute with the US which the Buenos Aires government had not sought. Apparently somewhat unwillingly, it then had to support Vernet, to protect its sovereignty claim. In turn, the British government then had to act to protect their sovereignty claim.

It is clear that Vernet's colony was essentially a personal venture and he looked to north European investors to settle the Falklands - not Argentines. He was prepared to place his colony under British protection, but once he had obtained an Argentine grant of land, Britain could not recognize his holdings. He is remembered by Mount Vernet west of Stanley.

References

Comments

Revisions

October 2019 Two additional photographs added; one reference added