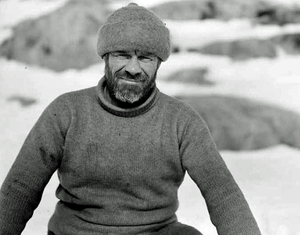

MARR, JAMES WILLIAM SLESSOR

1902-1965 from Scotland

King’s Scout, biologist and polar explorer and first leader of WWII Antarctic expedition ‘Operation Tabarin’, was born at Cushnie, near Turriff, Aberdeenshire, on 9 December 1902, the second son of John George Marr (a farmer) and Georgina Sutherland Slessor. He attended Aberdeen Grammar School and subsequently studied classics and biology at Aberdeen University. ( Awarded a B.Sc. in zoology and MA in classics in 1925).

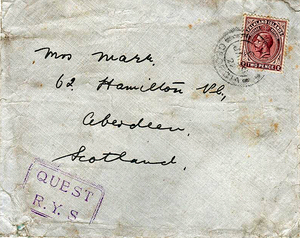

While at University, in 1921, Marr was one of two King’s Scouts selected to serve with the Shackleton/Rowett expedition, in the Quest, under the leadership of Sir Ernest SHACKLETON. He later wrote about his experiences in the Quest, in the book Into the Frozen South.

In 1925 Marr was appointed as a zoologist on the British Arctic Expedition, in the sailing ship Lady of Avenel, under the command of Frank Worsley - who described Marr as ‘being physically strong and an accomplished sailor’. After a year as a Carnegie Scholar at Aberdeen’s Marine Laboratory, in 1926, he was appointed zoologist in the Colonial Service – on the Discovery Investigations.

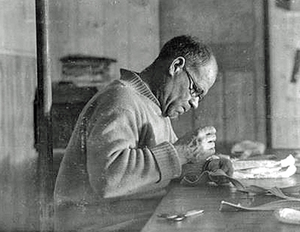

Marr was seconded to take charge of oceanography on the British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZAE) under Sir Douglas Mawson, (1929-1930). He took part in three expeditions to Antarctica in Royal Research Ships William Scoresby (1927-1929) and Discovery II (1931-1933 and 1935-1937). His principal field of research was a study of krill (Euphausia superba), which eventually culminated in the publishing of his 460-page magisterial paper – the ‘Discovery Report 32’, Natural history and geography of Antarctic krill. (Published just three years before his death in 1965).

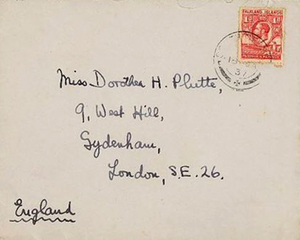

On 6 July 1937 Marr married Dorothea Helene Plutte (b.1915), fourth daughter of Gottfried Friedrich Plutte, of Sydenham; at Bramshott, Hampshire. The Marrs had two sons and three daughters (and one child deceased)

Between 1939-1940 he spent much of his time in the Antarctic in the SS Terje Viken, a whale factory ship owned by United Whalers Ltd, carrying out research into the canning, drying and freezing of whale meat for human consumption.

On 15 July 1940 Marr joined the Royal Navy as a Probationary Temporary Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). On 28 August 1940 he was appointed to HMS Baldur, the Royal Naval base at Reykjavik, Iceland. In August 1941 he was posted to HMS Pyramus, the Royal Naval base at Kirkwall on the Orkney Islands. In 1942 Marr was seconded to the South African Naval Forces, and his duties included serving in the HMS Jay, a minelayer, off the coast of Sri Lanka.

In September 1943 he was recalled to the UK and transferred to the Admiralty (HMS President) on his appointment as the leader of ‘Operation Tabarin’ and he was promoted Temporary/Acting Lieutenant Commander RNVR. Marr was described as:

Tall and gaunt looking, he was a dour Scot with a pawky sense of humour. Described by a contemporary as a genial man with a great gift for inventing jingles, he also enjoyed playing his mouth organ at bar-room sing songs and doing ‘turns’ with a comical twist. He was a great host with a hard head – ‘Let us mortify the flesh’ he would cry as he poured his guest a half tumbler of gin. (source; Vivian FUCHS).

In January 1943 the British War Cabinet gave approval for a Royal Naval mission to: ‘strengthen our title to the Antarctic Dependencies of the Falkland Islands, against which the Argentines were encroaching’ (source: Cabinet War Papers). The expedition was to include both military and civilian personnel, and also some scientists.

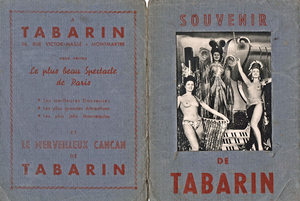

An Interdepartmental Committee was formed, and the recruitment of James Marr as leader of the expedition was its first decision. Two of the members of the Committee – John Mossop (from the Admiralty) and Dr Brian ROBERTS first gave the title of ‘Operation Tabarin’ to the expedition – named after a well-known, slightly risqué, nightclub in Montmartre, Paris.

The planning and execution of a clandestine Naval operation, the sourcing of ships and supplies and the recruiting of expedition members, in great haste, under the constraints of wartime, was a daunting prospect – but one in which Marr rose to the challenge. His two highest priorities were choosing of the members of the expedition team and the acquisition of a suitable vessel to transport the team and their equipment down to the Antarctic. Marr and the Interdepartmental Committee soon had the team assembled, but finding a suitable ship proved much more difficult. Marr travelled to Iceland to inspect SS Veslekari, a wooden sloop of approximately 280 tonnes. She was originally built as a seal catcher; she had previously been used on several expeditions in the Arctic. The ship sailed to the UK for refit and commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Bransfield. In the event this ship proved to be totally inadequate - eventually breaking down at Falmouth. The members of the expedition travelled south in the steamship Highland Monarch and the majority of the stores and supplies travelled down in the SS Groix, which departed UK on 25 October 1943. The expedition’s supply vessel Veslekari/Bransfield was later replaced by the SS Eagle – a Newfoundland sealing ship (crewed by Newfoundlanders and whose master was Robert SHEPPARD). The Eagle left for the south on 28 October 1944, arriving at Stanley on 17 January 1945.

Marr sailed from England in the Highland Monarch (being used as a troopship) on 16 December 1943. The ship also took the Falklands relief garrison of 200 members of Royal Scots Guards. The expedition arrived in Stanley on 26 January 1944. Immediately upon his arrival Marr had a meeting with the Governor – Sir Allan CARDINALL – when Marr was able to deliver copies of his secret operational orders. Marr also handed to the Governor a carefully worded document entitled ‘Political Instructions for the Governor’, who was designated as the person in overall control of the expedition.

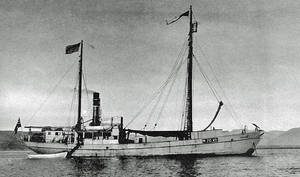

Negotiations then took place with Captain David W. ROBERTS, local manager of the Falkland Islands Company (FIC) to make use the company’s supply vessel Fitzroy to carry both personnel and stores/equipment down to the Antarctic to establish two bases. With the loss of HMS Bransfield, a second vessel was required, and HMS William Scoresby was made available for the use of the expedition. William Scoresby had been purpose-built as a research vessel for Discovery Expeditions but commissioned into the Royal Navy and refitted as a minesweeper, for wartime use around the Falkland Islands.

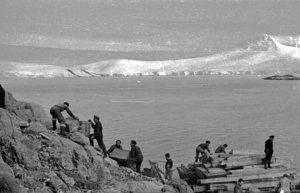

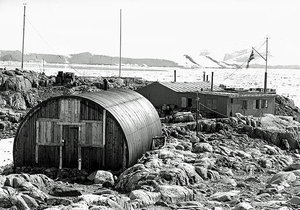

Marr and the members of the expedition and Captain Roberts, sailed from Stanley for Deception Island on 29 January 1944 in HMS William Scoresby and Fitzroy. Arriving at Deception Islands on 3 February. The base was quickly established utilising the existing buildings of the whaling station, abandoned in 1931. Men and stores and equipment were off-loaded, and the first base (Base B) was officially established on 5 February 1944.

The main Operation base was intended to be built at Hope Bay. But ice conditions were so poor upon reaching Hope Bay that the master of the Fitzroy (Captain Keith Pitt and Captain Roberts) flatly refused to take the non-ice hardened ship close into shore. Marr reluctantly agreed and the ships moved to the well-known anchorage at Port Lockroy and the first new base (Base A) was built there and officially established on 11 February 1944.

On 22 June 1944 Marr received a telegram from the Secretary of State for the Colonies, via Governor Cardinall: ‘Please inform Marr - a son born 1830 hours 18 June. Both well.’

Plans were drawn up to establish at least three more bases, and the expedition’s replacement supply vessel - the SS Eagle - arrived at Stanley on 17 January 1945. With the arrival of SS Eagle and more men, it became possible to establish Hope Bay (Base D) and an unmanned hut at the South Orkneys (Base C). Plans for another base at Stonington Island further south, were abandoned for that season. All this added greatly to the workload of Marr, who overwintered at Port Lockroy during 1944.

At meeting on 4 February 1945 on Deception Island, which included Kenneth BRADLEY, the Colonial Secretary in Stanley, Marr announced, to the amazement of the assembled members of the expedition, that he intended to return to England because he had not been entirely fit for some months – which had been made much worse for him because of serious back problems. After consultation with the Colonial Office, he intended to hand over command of ‘Operation Tabarin’ to Captain Andrew Taylor (Canadian Army) on 8 Febuary1945. Everyone at the meeting tried to persuade to reconsider his decision, but he was adamant, saying his mind was definitely made up. Marr was physically and mentally exhausted.

Surgeon Lieutenant E H Back RNVR, the Medical Officer with ‘Operation Taberin’, admired Marr greatly:

Marr worked like the proverbial Trojan, and he got things going – how he did it, I don’t know. On the other hand, he did have a habit of, if there were two ways to do any job, he would choose the difficult way; he seemed to revel in doing things the hard way, which sometimes was a bit difficult if you were working with him. He was a loner, very much so, but Davies had worked with him before, and Davies was extremely loyal to him. But Marr kept his own counsel, he obviously had secret orders – presumably he knew what we were supposed to do – if he was, he was the only person who did. I’ve no doubt the instructions were, “That these are top secret, and you keep them to yourself.” So that with those instructions he was to some extent like the captain of a ship – he was on his own and he couldn’t have any confidants. But I admired Marr, I think he did very well, and I found out afterwards that he was unfit because he had a duodenal ulcer and he’d had injured his back in the past, but he wouldn’t have known that during the time that he was with us. And he’d put his heart and soul into it, and as you probably are aware that, during the second year, he was supposed to put up in Hope Bay and he decided that he would not be able to carry on, and he was going to resign at the end of the season I think [after] establishing Hope Bay. And then he was taken acutely ill, and the ship was sent for and he had to go back in a hurry to Port Stanley. Certainly, he worked extremely hard, and nobody could have worked harder than he did. (source: British Antarctic Survey: Oral History Recording No 4. Archive reference AD6/16/1986/4.1)

Back later wrote a confidential report on Marr:

Lt.Cdr. Marr is suffering from mental and physical exhaustion associated with depression. He requires very careful observation and treatment since suicide is not unknown in such cases …He has a marked tremor, cannot sleep and worries a great deal. He is the type of man that will not give in but keeps on and on until he is exhausted. Under the circumstances I feel it is essential that he should leave the Antarctic at once. (Source; BAS G12/1/3/4 8 February 1945). Marr returned to Stanley and then to England in the spring of 1945.

After the cessation of hostilities at the end of WW2 ‘Operation Tabarin’ was transferred from military to civilian oversight and was re-named ‘The Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS)’, later this became the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

At the end of WW2 Marr re-joined the Discovery Investigations. He also spent time working at the Natural History Museum, London, continuing his research on krill. In 1949 he was appointed Principal Scientific Officer in the Royal Naval Scientific Service at National Institute of Oceanography at Godalming, Surrey. He held this appointment until his death in 1965.

Marr was awarded the Scouts' Silver Cross and the Bronze Medal of Royal Humane Society in 1919. He was awarded the W.S. BRUCE Memorial Prize of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society in 1936, and the Back Grant of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) in 1946. He was awarded the Polar Medal three times – the Bronze Medal in 1934 and the Silver Medal twice in 1941 and 1954.

James Marr died on 29 April 1965 at Milford Chest Hospital, Busbridge, Surrey. His widow, Dorothea (known as ‘Bunny’) died in 1982.

The noted polar authority, Brian ROBERTS wrote about Marr in an obituary that::

His Antarctic experiences began in the dying phase of the ‘Heroic Age’ of adventurous personal enterprise and ended when these same activities, often no less adventurous, had largely become a routine government commitment. During the Second World War the rapid transition from one age to another was not easy for the few who were actively concerned with Antarctic affairs. The part which Marr played may well come to be regarded as of more far-reaching significance than his biological researches. (Source: Brian Roberts; ‘Obituary for Dr JWS Marr’ Polar Record. 1965)

External links

See: Operation Tabarin - overview

See: British Antarctic Survey Oral History Project: A recording of Dr EH Back, Medical Officer with OperationTabarin between 1943 and 1946,

References

Fuchs, Sir Vivian E. (1982). Of Ice and Men. The Story of the British Antarctic Survey 1943-1973. Anthony Nelson.

Haddelsey, S. (2014). Operation Tabarin: Britain's Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica, 1944–46. Stroud: History Press. ISBN 9780752493565.

Pearce, Gerry (2018). Operation Tabarin 1943-45 and its Postal History. ISBN 978-1-78926-580-4.

Comments

Revisions

June 2023 Biography first added to Dictionary

July 2023 Text updated