The CHALLENGER EXPEDITION

1872-1876 from England

a scientific research voyage which made many discoveries and laid the foundations of the science of oceanography. The expedition was named after the Royal Naval vessel which undertook the trip - HMS Challenger a steam-assisted screw corvette of 2306 tons. The ship sailed from Portsmouth on 21 December 1872, and during the four-year voyage she travelled approximately 68,890 nautical miles (79,280 statute miles or 126,848 kms).

Captain George Nares FRS commanded the ship until her arrival in Hong Kong, from where he was recalled, having been appointed to lead the British Arctic Expedition 1875-1876, using HMS Alert and HMS Discovery, in an attempt to reach the North Pole.

Charles Wyville Thomson (1830 –1882) was the chief scientist in charge of the expedition. He was a Scottish natural historian and marine zoologist. His work during the expedition led to his knighthood. Another scientist on the expedition was John Murray (March 1841 – March 1914) who was a Canadian-born British oceanographer and marine biologist He is considered to be the father of modern oceanography.

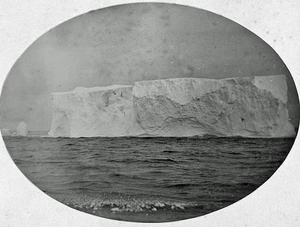

The ship first sailed from England - south and west via the Canary Islands, Bermuda, Halifax Nova Scotia, Brazil, Tristan da Cunha and the Cape of Good Hope. In the Southern Ocean she visited the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Island and Heard Island, before arriving in Australia. During 1874 the ship visited New Zealand, Tonga, Fiji, Hong Kong, Indonesia, New Guinea, the Philippines, Japan, and Hawaii. On 23 March 1875, in the southwest Pacific Ocean between Guam and Palau, the crew recorded a sounding of 4,475 fathoms (26,850 ft; 8,184 m) deep, which was confirmed by an additional sounding. This area represents the southern end of the Mariana Trench and is one of the deepest known places on the ocean floor. This area now bears the name ‘The Challenger Deep’. Travelling east across the Pacific Ocean, the ship explored the west coast of South America, and Tierra del Fuego, before heading north around Cape Horn, and paying her brief visit to the Falklands.

The ship arrived in the Falkland Islands from Sandy Point {Punta Arenas} on 23 January 1876 commanded by Captain Frank Tourle Thompson RN (who had succeeded Nares in Hong Kong). She had a total complement of 230 people, and she left the Falklands a week later, reaching Montevideo in Uruguay in mid-February 1876.

One of the expedition’s scientists – Henry Mosley (1844-1891) – was less than enthusiastic about his first impressions of the Falklands. He rode from Stanley to Port Sussex and noted that:

The Falklands are a treeless expanse of moorland and bog, and bare and barren rock … A bitterly cold hailstorm pelted my face as I was rowed to the shore … The islands are occupied with cattle and sheep runs … the mutton is excellent, but the supply is so far in excess of the small demand, that the Falkland Islands Company has a large boiling down establishment, where the sheep are boiled down for tallow. [outside Stanley] … at every ten miles or so a shepherd’s cottage was met with. Usually, the shepherd was a Scotsman … they seem well off and were very hospitable … each of the Company’s shepherds had eight horses and a pack animal … Though most of the gauchos have gone some of their language remains.

Henry Mosley’s sixty-mile cross country journey followed a request from Governor D’ARCY to Wyville Thomson to investigate the possibility that ‘Plumbago’ (an old name for Molybdenite or Graphite) deposits had been found in the Port Sussex area. In the event no such deposits were found, and Governor D’Arcy wrote a note of thanks to Wyville Thomson on 5 February 1876:

I trust you will accept the sincere thanks of this Government for this service although a valuable mineral has not been found, yet the question is now set at rest, sheep farmers and other Colonists will [be content] to realise the small but secure profits arising from their pastoral occupations instead of speculating in uncertain mining operations.Will you be pleased to convey to Mr Mosley how much I feel indebted to him for the prompt and zealous manner he carried out your orders. It will afford me great pleasure to report … how much this Government feels the kind interest you have taken in endeavouring to develop another article of export from these islands.

During the ship’s stay in the Falklands one of the crew tragically lost their life in an accident. Able Seaman Thomas Bush was returning to the ship when he fell overboard from the pinnace. Despite the valiant efforts of Lieutenant Alfred CARPENTER, who jumped into the sea at night in an attempt to rescue Bush, the seaman drowned. Bush was later buried at Port Louis and Carpenter was subsequently awarded the Albert Medal for his act of great bravery.

Governor D’Arcy also wrote a very appreciative letter on 5 February 1875 to the captain of the Challenger:

Will you allow me to express my acknowledgement for the assistance you have given this Colonial Government in testing the present accuracy of the mean level of the ocean, taken thirty years ago by Her Majesty’s ships Erebus and Terror. I will cause the results of your observations to be made known to the naval authorities of the United States, who were the first to suggest the necessity of this Inquiry for scientific purpose connected, I fancy, with some geological researches they had in their view.Meanwhile, I hope you will let me add the expression of how much we are indebted to yourself, your officers, Professor Thompson [sic],and the scientific staff, for your courtesy and hospitality [in] throwing the Challenger, with all the curiosities onboard, open to the inspection of all classes of Colonists.

The ship left Montevideo at the end of February, arriving at Ascension Island at the end of March 1876. Challenger returned to Spithead, Hampshire, on 24 May 1876, having spent 713 days out of the intervening 1,250 at sea.

The expedition also confirmed the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge extending from the southern hemisphere to the northern one. During the ship’s circumnavigation of the earth 480 deep water soundings were taken and more than 4,700 new species of marine life were discovered. The fifty reports of discoveries made during the Challenger Expedition continued to be published in scientific journals until 1895.

The Challenger Expedition was a remarkable scientific enterprise and as the oceans continue to be explored, ‘more scientific discoveries will be made that tell us more about our world's past, present and future. Much of it will continue the work of HMS Challenger, the impact of which continues to shape scientific thought today’. (From the Introduction to the listing of Challenger specimens held in the Natural History Museum, London).

Editorial comment:

Sir Charles Wyville Thomson, Henry Moseley and Sir John Murray were all Fellows of the Royal Society (FRS). Their other academic qualifications were Thomson FRSE FLS FGS FZS; Murray FRSE FRSGS.

External links

For the text of the Report of the Challenger Expedition see:https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/72085

References

1. Challenger Expedition (1872-1876) - Great Britain. Challenger Office. - Buchan, Alexander, - Huxley, Thomas Henry, - Murray, John, Sir, - Nares, George S. (George Strong), Sir - Nares, George Strong, Sir. - Pelseneer, Paul, - Thomson, C. Wyville, (Charles Wyville), Sir, - Thomson, Frank Tourle - Thomson, Frank Tourle - Challenger (Ship) Publication info: Edinburgh, Neill, 1880-1895

2. REPORT of the SCIENTIFIC RESULTS of the VOYAGE OF H.M.S. CHALLENGER DURING THE YEARS 1873-76 under the command of Captain GEORGE S. NARES, R.N. F.R.S. and the late Captain FRANK TOURLE THOMSON, R.N. Prepared under the Superintendence of the late Sir. C. WYVILLE THOMSON, Knt., F.R.S., &c. Regius Professor of Natural History in the University of Edinburg Director of the Civilian Scientific Staff on board and now of JOHN MURRAY, LL.D., Ph. D. &c. One of the naturalists of the expedition. December 1886

Comments

Revisions

December 2022 Biography first added to the Dictionary