STRANGE, IAN JOHN

1934 - 2018 from England (also Falkland Islands)

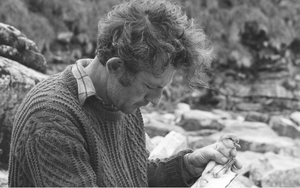

naturalist, conservationist, wildlife artist and photographer was born on 20 July 1934 in Market Deeping in Lincolnshire, the son of Leonard and Vera Strange (neé Corfield). His father was a master craftsman specialising in wood carving – his main work was in churches in the Peterborough and Ely areas.

Strange attended secondary modern school in Wolverhampton. He then studied at Wolverhampton College of Art, specialising in botanical illustration. Strange studied botany as an extra-mural student at Birmingham University, and completed a degree in agriculture at Essex Agricultural College.

He joined the British army for national service, serving with a specialist unit in the 16th Independent Parachute Brigade, most of his time being spent in the Middle East.

In 1959 Strange was recruited by the Hudson’s Bay Company, for the Falkland Islands Company Ltd (FIC), to travel to the Falklands to manage a venture aimed at diversifying the local economy away from a virtually exclusive dependence on sheep farming. FIC proposed that mink could be reared for their pelts on the surplus sheep meat – the Falklands’ industry was then largely based on wool production and surplus animals were simply culled. Mink were not present on the Islands and Strange had previous knowledge of breeding mink, having farmed them with his young wife in England. He and his wife - plus the mink and two red setters - arrived in Stanley on Christmas Eve 1959.

The eventual closure of the mink farm in 1966 can in no way be attributed to the thorough and professional manner in which Strange executed his duties. The project failed as the result of several factors – despite the fact that Strange proved that the venture could be profitable - rising costs, changes in clothing fashion and the unsuitability of mutton as the primary food for the mink, forced the FIC to close the mink farm for economic reasons. It is somewhat ironic and a tribute to his foresight and the concern he had developed for the wildlife of the Falklands that, on winding up the project, he personally undertook the complete extermination of a species from the Islands. Had some of the mink under his charge escaped into the wild, the consequences would have been disastrous for the bird population of the Falklands.

Strange knew on arrival in the Falklands that he would become immersed in the landscape, wildlife and natural history and it was not long before he took every opportunity to explore nearby coastlines and offshore islands, acquiring the Gleam, a 10-ton cutter. He discovered with some concern that early estimates of fur seal and sea lion colonies dating back to 1930 were outdated and inaccurate, giving the local government no authoritative information on which to base decisions about the granting of sealing licences. He carried out his own surveys by overflying known colonies and searching remote islands and coastal areas for new breeding grounds. His estimate that sea lion numbers were less than 10% of those reported over 30 years earlier was potentially shocking. Fur seal numbers were similarly drastically low.

Beauchêne Island is a remote outlying island, the most southerly of the Falkland Islands and is difficult to access.Strange made his first visit in 1963 (with the help of the Royal Navy), and he saw the tremendous importance of this island with its huge populations of seabirds as one of the Falklands’ greatest assets. He campaigned for its protection over many years.During subsequent visits eventually made to Beauchêne Island, no fur seals were found to remain there. Without Strange’s approval, his survey results, which were written up in the UK by Bill Vaughan of the British Antarctic Survey (who had collaborated with him in the seal survey), were released to the Falkland Islands Government. This gave the government the opportunity to suppress the report and to allow sealing to recommence in 1965. However sealing activity soon ceased because there were too few seals to be economically hunted.

Strange continually pressed for adequate protection for small untouched offshore islands and islets, particularly those which still held tussac grass cover which had not been overgrazed or totally eaten out by sheep. Within a few years of his arrival, he was making recommendations to the government on matters of wildlife and conservation importance and this paved the way for the passing of early legislation, in 1964, which gave protection to some pristine offshore islands.

The remote Jason Island group to the far northwest of the Falklands, in Strange’s view, held the key to the survival of much of the Falklands’ wildlife. Steeple. Elephant and Grand Jason Islands were privately owned and stocked with sheep until 1971. Animal grazing had decimated substantial areas of valuable tussac grass. The remaining smaller islands of the group were Crown owned. Strange pressed for adequate protection for all the Jason Islands. Strange was a catalyst in the eventual purchase of Grand and Steeple Jason – by Len Hill, the philanthropic owner of Birdland, an avian wildlife park in England.Although he would have preferred a purchase by a recognised international wildlife organisation, Strange put considerable personal effort into supporting Hill in his efforts for the purchase.Eventually Steeple and Grand Jason passed to the Wildlife Conservation Society of New York and remain under their protection today.

Roddy Napier, owner and resident on nearby West Point Island, practiced sustainable management of tussac and other grasslands on West Point and, as a result, the island was a haven for wildlife, something which Strange greatly admired and respected. He and Napier became good friends and supported each other in the eventual purchase of New Island, one of the most significant developments in wildlife conservation in the Falklands in the early 1970s.

The value of tussac grass to the Falklands has long been recognised.Over much of his active career in the Islands Strange documented the extent and quality of tussac stands, drawing attention to the huge losses of this valuable coastal habitat since sheep farming had been introduced and inadequate fencing off of the tussac plantations had occurred.

The Falklands holds large populations of upland and ruddy-headed geese, species which some farmers felt were significant competitors for the grassland resource and therefore should be seriously culled. The 1905 livestock Ordinance allowed for the payment of a bounty on beaks of geese killed. Strange argued that persecution was relatively ineffective and that strategic siting of areas of grass re-seeding, and other grassland improvement practices to avoid large groups of geese, would prove more effective. These suggestions were later verified by the findings of a significant research programme in 1982 (by SUMMERS and Grieve) on these species.

On completion of the mink farm project, in 1966, Strange and three friends undertook a 22,000-mile journey overland from Montevideo in Uruguay to San Francisco and on to New York in a Land Rover he had rebuilt in the Falklands. All along this journey he was able to observe wildlife and to assess land management practices.In the USA he wrote articles and gave illustrated talks to promote what the Falklands had to offer in terms of natural history and lifestyle. Strange made a number of very useful high-level contacts who would later assist him in his conservation work.

While in New York at the end of the road trip Strange met pioneer travel operator Lars LINDBLAD at the point when the Swede was about to launch the first small expedition cruise to the Antarctic – at that time in a chartered vessel, later building his own MV Lindblad Explorer. Strange suggested that the Falklands might be included in the itinerary, and pressed for calls at Stanley, West Point and Carcass Island. Thus, began small expedition ship tourism to the Islands.

In 1972, with Annie Gisby and Roddy Napier, Strange was able to purchase New Island. He saw this as being the perfect platform to demonstrate how sheep farming and specialist wildlife tourism could be managed and the flora and fauna studied in a reasonably pristine state, even though the island had been ravaged in the past by sealing, whaling and more recently depredation by sheep. Sheep farming continued on a reduced scale, but this was eventually phased out.

Focus was then turned to all aspects of natural history research to allow long term projects, several of which continue to this day.In the hope of protecting the island and its projects in perpetuity, Strange founded and developed what is now the ‘New Island Conservation Trust’, a non-profit charitable conservation organisation. Reaching this point was not without many trials and tribulations but Strange’s fierce independence and determination did not waver in achieving his objective.The island was the focus of over 40 years’ work, and it was an uphill struggle to ensure its protection, during which time he continued to operate the day-to-day running of the reserve. Through personal contacts he was able to secure funding for a field station to be constructed on the island, the first purpose-built field research facility in the Falklands and one which has welcomed scientists and field workers since 1999.

New Island’s links with the eastern seaboard of the United States were of great interest and Strange made research visits, particularly to Nantucket, from whence came many of the early sealers and whalers who plied Falkland waters came from in the 18th and 19th centuries.The Island’s link to Captain Charles BARNARD was especially researched and much of the restoration of the building at the head of the settlement harbour, named after the marooned captain, was carried out by Strange and volunteer helpers.

Strange remained an honorary adviser to the Falkland Islands Government (FIG). and from 1982 to 2013 he also advised the Ministry of Defence on environmental matters.

Ian Strange championed the creation of marine reserves, submitting proposals to FIG on several occasions. When FIG proposed in 1998 revising the existing Wild Animals & Birds Protection Ordinance and Nature Reserves Ordinance, he was asked to suggest principles for, and make proposals on, new draft legislation for use in the Falklands.

In early 1988 Strange was requested to produce a report covering the many different aspects of conservation in the Falkland Islands, with recommendations to assist the formulation of policy and new legislation. His substantive 1989 report was a watershed document.

Ian Strange published his first book, The Falkland Islands, in 1972. It became the standard source of information on the islands. The book was revised in 1981 and had a third edition, in 1983, updated to include the impact of the Falklands conflict. The research involved in writing the book resulted in Strange becoming familiar with the contents of the Falklands’ archives, and over a number of years he championed the need for suitable storage and protection of records and books. which for far too long had not been afforded a proper depository.He strongly supported the Falkland Islands Journal, contributing an article (The Conservation of Wildlife) to the first issue in 1967 and serving in an editorial role in 1973.

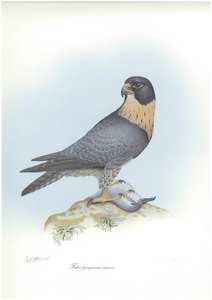

Strange subsequently produced several more books (some with his daughter, Georgina) on Falklands wildlife, nature and the beauty of people and landscapes through photography. He was particularly pleased to be able to write and illustrate the Collins Field Guide to the Wildlife of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, which remains in print to this day. Strange also wrote many popular articles on Falklands wildlife in high-profile magazines and journals and most of his research passed peer review scrutiny to appear in appropriate scientific publications.

In the 1970s Strange became a Crown Agents stamp illustrator and designer, and while paintings and photographs by and of Falkland subjects had already appeared in postage stamps, he was the first to complete a Falkland design fully ready for security printing. In more recent years he used a computer to produce various designs using his photographs as well as some of Georgina’s, whom he encouraged to take on similar work.

Strange fully realised the impact that offshore fisheries could have on wildlife and conducted population estimates of key species such as the black-browed albatross, introducing careful aerial surveys and detailed counts using high definition photography and backed by computer technology for accuracy.

Strange also participated actively and gave informed opinion when preparations for oil exploration began in the late 1990s, taking part in advisory groups and familiarisation visits overseas.

Ian Strange was not a man to compromise on principle and although he was often portrayed as rather intransigent, in hindsight, a wider view of his position can be taken. He did accept the need for multi-functional use of the land resource and did not find this incompatible with wildlife conservation. He believed strongly in co-existence even if only for economic reasons, but wildlife was his clear priority.

Strange was both a man before his time and a man ahead of his time.In the 1960s, farming in the Falklands operated as a semi-feudal system under the control of a small number of landowners (often expatriate) who managed very large farms on a minimal input basis. Conservation did not feature high on their agenda and his warnings, proposals and recommendations often raised objections or fell on deaf ears.Some farmers actively opposed him, regarding him as an interfering nuisance. The recommendations of Lord Shackleton’s Economic Survey team in 1976 that the land ownership issue needed to be addressed by subdividing the large farms into smaller, largely family-based units and transferring ownership from the company structure to mostly individual Falkland Islanders, revolutionised the farming structures and attitudes in the Falklands. Post-Shackleton, wildlife was seen in a different light and tourism gradually became a significant new revenue source. Strange never opposed increasing the exposure of wildlife and the natural environment to tourism – indeed he was one of its earliest and primary advocates.

Those who respected his pioneering efforts and took the time to consult him, found that behind a somewhat shy, quiet and reserved exterior was a generous and kind man who was always willing to give wise and sensible advice based on his vast experience and expertise. Strange was a man who was willing to compromise, and always saw the positive side of people and situations. Despite his prodigious published output, he was not comfortable writing for publication, and found it a struggle.

Strange was a very practical person, skilled in working with wood - and his practical abilities were seen in his management of the mink farm, how he lived in the Camp and also in his travels around the islands and further afield. Throughout his life, in whatever tasks he undertook, Ian Strange developed a strict work ethic.

Ian Strange married first Irene Hutley in England in 1958. They had three children: Shona Marguerite, Sharron Irene and Alistair Ian. He married, secondly, Annie Gisby in the Falkland Islands in 1969.Ian and Maria Marta Villanueva worked and lived together from the mid1970s; they had a daughter, Georgina, and were married in the Falklands in 1984.

He was awarded an MBE in the New Year’s Honours in 1992.

Ian Strange has been described as the modern successor to Audubon, and his paintings with their clear, crisp lines and attention to detail are much sought after.

A great believer in “conservation for everyone” Strange was greatly encouraged by younger Islanders who took up the challenges and purchased and put aside land and small islands as private reserves.

There is no latter-day advocate to replace Ian Strange. The cause he started and struggled with, often alone and against fierce resistance in the early days, is now firmly embedded in the policy and practice of local government, society and the farming and tourism sectors in the Falklands. Much of the work is now being undertaken by NGOs such as the New Island Conservation Trust and Falklands Conservation, a local membership non-governmental organisation which works to conserve the natural environment of the Falklands for future generations and which owes him an immense debt of gratitude. All now follow the path he laid out. Such is his legacy.

Ian Strange died at South Brent, Devon, on 30 September 2018, aged 84, and was laid to rest on New Island, as was his wish.

External links

See: For full version of 'Appreciation' Falkland Islands Journal 2018

See: Obituary -The Daily Telegrapgh 16 December 2018

References

For full bibliography of books, sound recordings, reports (sole and joint authorship), scientific papers (sole and joint authorship), printed articles in journals and magazines, see Falkland Islands Journal; 2019

Books:

1972 – The Falkland Islands. David & Charles, Devon UK ISBN9 7807 1535 5855

2nd edition 1981ISBN 0 7153 8133 4

Revised edition 1983ISBN 0 7153 8531 3

1976 – The Bird Man: An Autobiography. Gordon Cremonesi, London. ISBN0 86033 015 X

1981 – Penguin World. Dodd, Mead, USA. ISBN0 396 08000 6

1985 – The Falklands: South Atlantic Islands. Dodd, Mead USA. ISBN 0 396 088616 0

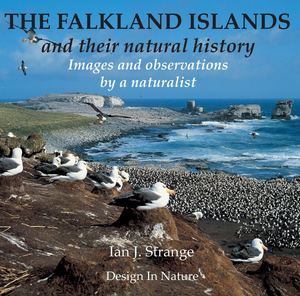

1987 – The Falkland Islands and their Natural History. David & Charles, Newton Abbot, Devon, UK. ISBN0 7153 8833 9

1992 – A Field Guide to the Wildlife of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia. HarperCollins. ISBN 0 00 219 839 8

1996 – The Striated Caracara Phalcoboenus australis in the Falkland Islands. Author.

2005 – Atmosphere: Landscapes of the Falkland Islands. (with Georgina Strange). Design In Nature. ISBN 9 955 0708 0 5

2007 - New Island, Falkland Islands: A South Atlantic wildlife sanctuary for conservation management - New Island Conservation Trust. (with Georgina Strange) Design In Nature ISBN 978 0 9550708 1 3

2009 A Penguin’s World.Ian and Georgina Strange.Design In Nature

ISBN 978 0 9550708 2 2

2014 The Falkland Islands and their Natural History: Images and Observations by a Naturalist

(with Georgina Strange) Design In Nature ISBN 978 0 9550708 4 6

2014 Unknown Beauty: images of beautiful unknowns Design In Nature ISBN 978 0 9550708 3 9

Comments

Revisions

January 2020 first added to Dictionary